Funding

For the fall 2025 semester, 19,895 students were enrolled at UNCW. Of that population, about 10% are Hispanic, and 6% are Black. However, that includes online students; looking just at on-campus students, those numbers drop to 8% and 2%, respectively. That means Hispanic students are slightly underrepresented on campus compared to statewide demographics, where Hispanic residents make up close to 11% of the population. It leaves Black students significantly underrepresented compared to the state, where Black residents make up roughly 20% of the population (in New Hanover County, it's closer to 12%).

While Black and Hispanic students constitute a smaller share of UNCW’s population, there was previously a focus on programming to support them. That changed with the new equality policies passed by the UNC System Board of Governors. Many of these targeted programs and personnel were restructured to support all students, and the funding followed.

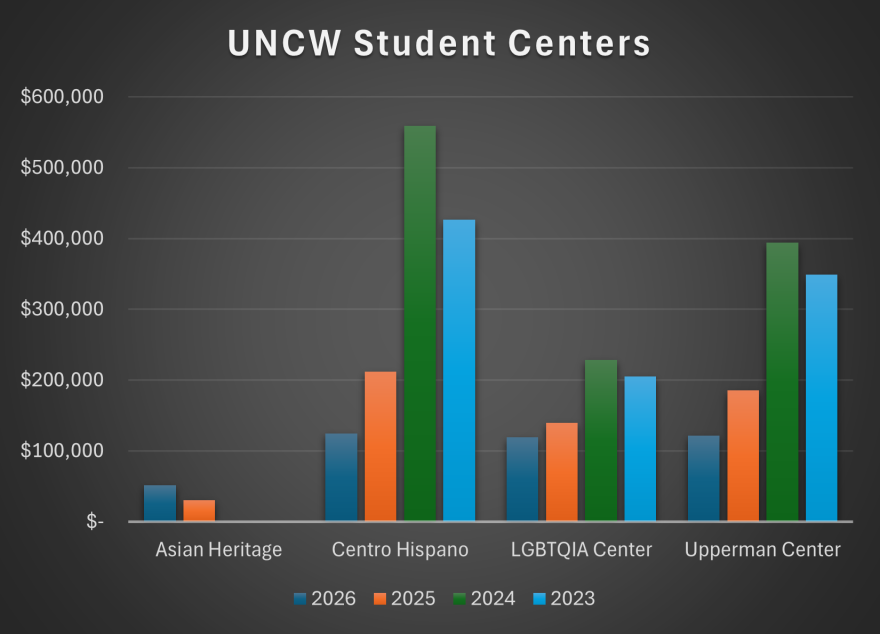

Over the past four years, UNCW’s Centro Hispano’s budget has declined by 71%, the Upperman African American Cultural Center decreased by 65%, and the Mohin-Scholz LGBTQIA Resource lost 42% of its funding. The only outlier is the Asian Heritage Cultural Center, which began operating on a budget in 2025, and whose funds have increased by 70%.

The steep budget cuts were intended to bring those student centers into compliance with the UNC System’s equality policy. UNCW’s August report to System President Peter Hans noted that $1.4 million from positions had been reallocated to general student success initiatives.

Impact of budget cuts

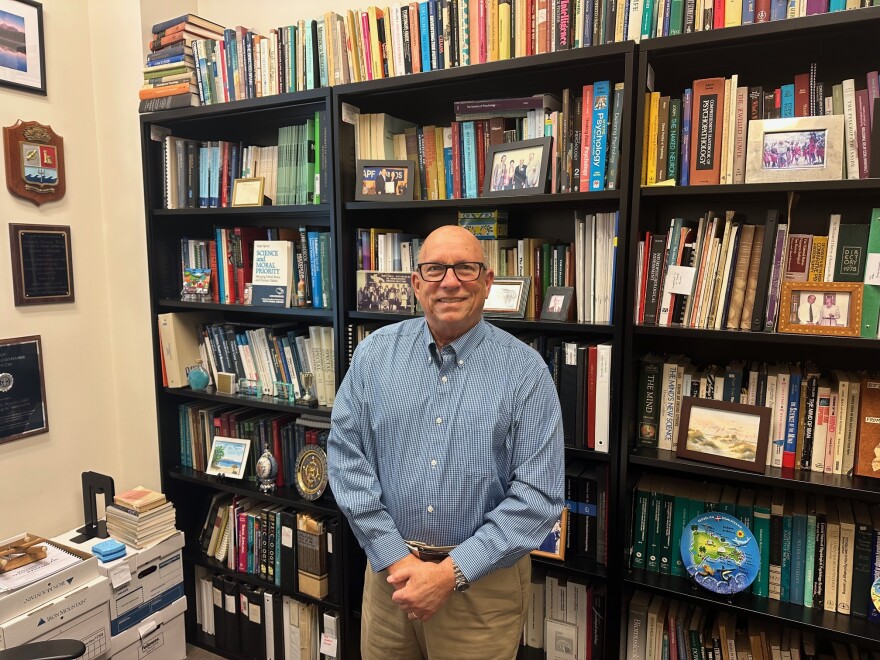

UNCW psychology professor Dr. Antonio Puente was the founding director of Centro Hispano and was one of the leaders during its creation some 20 years ago. The center once had upward of seven staff members. It now only has one.

“It's hard to define how do we do it, [we have], a middle level manager who's pulling her hair out doing her very best with a small cadre of student assistants and now a re-emerging faculty advisory committee, which I might share is of tenure track or tenured professors, for obvious reasons, and our goal is to support, whether it's financial, emotional or even policy-wise,” he said.

With regards to Centro Hispano’s diminished funds, Puente said, “Oh, gee whiz, [in 2024], we had over half a million dollars.”

This fiscal year, they have $124,723.

One reason for scaling back the operations of Centers like Centro Hispano is that, according to the UNC System Board of Governors, they were places where equal opportunity wasn’t necessarily being provided.

“It's a new world out there. And we're following the lead of the Board of Governors and the laws of the state of North Carolina, where diversity, equity, and inclusion are not considered acceptable concepts or words,” Puente said.

Manny Lloyd, a UNCW alum, a leading member of the Coalition of Black Alumni, and a former staff member of the Upperman African American Cultural Center, said there is fear around certain words and phrases.

“And if we're afraid of language, I mean, our university's motto is dare to soar or dare to learn. And if we don't want to learn, then I think that this counteractive to who we are as an institution,” he said.

What the Centers stood for

Lloyd remembers what Upperman meant to him.

“It taught me about my history, about my heritage, about my culture, and it gave me language for some of the things that I was experiencing,” he said.

Puente also reminisced about Centro Hispano’s founding. He said former UNCW Chancellor Jim Leutze supported the idea.

“There was no office, there was no budget, there was no nothing, just a group of faculty that believed that we should reach out to this underserved and, I would say, poorly misunderstood, community,” he said.

Lloyd said he refutes the idea that UNCW students were being indoctrinated with certain ideologies.

“It never told me to act in any sort of way. We never told students how they should believe, what they should believe,” he said.

Puente agreed that these Centers were never meant to be exclusionary.

“The idea is that let's look at the beauty of life in all its colors and all its forms. And these are forms and colors that we have historically not understood. So let's make sure all are considered, all are appreciated, and all participate in making this country the great country that we are,” he said.

Lloyd said there used to be about 40 Upperman programs a semester, between academic, social, pre-professional, and cultural programming run by about four employees.

He added that he really enjoyed planning events such as the Black Men’s Initiative, the Kwanzaa celebration, Juneteenth Empowerment, and alternative spring break trips. He also spent time organizing talks around Gullah Geechee culture and supporting the literary publication Seabreeze: A Literary Diaspora.

“And all that has kind of stopped. I don't think it had to,” he said.

The August 2025 compliance report

Part of the UNC System’s new equality policy requires compliance reports on how identity-based programs are being converted to serve all students.

UNCW’s 2025 compliance report notes several examples, including the Coastal ROOTS summer program, a relatively new effort to help incoming students dealing with a variety of challenges, including students from minority, rural, and low-income backgrounds, as well as student-athletes and out-of-state students. The program initially supported a lot of Black and Hispanic students, but has since morphed into the Summer Bridge, with a focus shifted to economic background rather than race.

“And it was primarily dedicated towards Black and Brown students. It went from being something that was meant to support a certain group, and then it was, ‘Okay, now, it's open to everyone,’” Lloyd said.

The report also noted that the MI CASA program, which previously served prospective and incoming Hispanic students, was renamed the Precollege Mentoring Program to “better reflect its inclusive mission for all prospective students [...] While MI CASA previously focused on serving Hispanic student populations, it was moved to Academic Affairs and broadened to be openly accessible to all North Carolina high school students.”

The equality policy also required that Center activities had to be student-led, so that faculty could only assist and not initiate. Lloyd and Puente see problems with this.

“They can put the programming out, but they're also students, and they're there to go to school; that’s not necessarily their job, right?” Lloyd said.

Puente added, “So it's hard to ask these individuals with no prior experience and a heavy load and other demands on their life to surmount what people like [former Centro Hispano Director] Edelmira Segovia, who had her doctorate, to achieve these goals, so they're doing the best they can, and sometimes not as well.”

The Coalition of Black Alumni got few answers

Lloyd, who led the charge to stop some of these programs from being cut in 2024, said that many former staff members of these Centers weren’t even consulted.

“They found out a day before it was announced to everyone at the community at large that they were reassigning positions. They had not been included in any meetings up until this. It was very much top-down,” he argued.

Back in 2024, Lloyd and others in the Coalition of Black Alumni (COBA), an independent association separate from the university's official Black alumni association, tried to schedule meetings and get answers from the upper administration, including Chancellor Aswani Volety at UNCW.

Their requests fell on deaf ears.

“And that is what really is aggravating, really about the whole situation, and makes it difficult to really be, for me, a really proud alum, just because of how it all went down,” he said.

Lloyd, along with COBA, submitted a 20-page proposal in August 2024 outlining how they could reimagine the Centers in light of the UNC System's new directives. They were ideas for rebranding the Centers while keeping staffing and programming. There were also concessions built in. (*You can view this at the end of this article.)

Lloyd said those were not taken into consideration. A couple of the report pages were worked on by Center staff, according to Lloyd, but were also ignored.

In early September 2024, Volety wrote that they are already meeting with “student leader leaders who represent the Upperman African American Cultural Center and with alumni who represent the UNCW African American Graduate Association (AAGA),” writing that COBA should advocate with AAGA.

While the Chancellor didn’t take up the meeting, COBA still had 21 specific questions about the future of the Centers to which Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs Christine Davis responded, “We are actively working with officially recognized UNCW alumni groups [...]. Additionally, we do not discuss university operational matters with outside entities. As such, we will not be addressing specific questions you raised in your inquiry. [...]. Moving forward, please be advised that any further correspondence from anonymous senders or unrecognized groups will not receive a response.”

It's true that governmental institutions don’t have to answer questions, except where specifically identified by public records law. Still, if an anonymous or named person submitted a public records request, the university would, by law, have to fulfill it.

COBA, through Lloyd (who was unnamed at the time), then attached a UNCW representative's name to every submitted question. Reed Davis never responded to those.

This month, WHQR asked UNCW spokesperson Sydney Bouchelle if any concerns had been addressed from the COBA-submitted proposal. She echoed Reed Davis's sentiments from over a year ago.

“While the university appreciates feedback from alumni, UNCW did not enact suggested actions proposed within the document, which was sent anonymously by the Coalition of Black Students and the Coalition of Black Alumni on August 30, 2024,” Bouchelle wrote.

Norms are changing

The future of using specific words and phrases remains in question. While UNCW’s August compliance report mentions the word “inclusive” three times and “belonging” two times, it does not mention DEI unless it was a directive to eliminate it.

Puente said there is a reason for allowing an iteration of “inclusion.”

“Inclusion assumes that everybody has equal opportunity, whether you're a majority group culture member who belongs to a country club, or if your father is a migrant worker who picks cotton and tobacco. Of course, that assumes certain things, and that assumes that everybody does have equal opportunity,” he said.

Puente said the centers are supposed to be a place where students and faculty can thrive — but that’s become more challenging in the current political environment. Puente, who was undocumented himself for 12 years before becoming a U.S. citizen, said he’s concerned — for himself and for others who are immigrants on campus. About 2% of both UNCW students and faculty are on visas.

“Having lived in two countries [Cuba and Grenada] that went communist, I will tell you that we're involved in a serious social experiment, as we speak. It seems strange that a tenured faculty member who was president of the American Psychological Association feels the need to carry his passport with him, but here we are,” he said.

What’s next

Puente has been at the forefront of Centro Hispano from the very beginning. He doesn’t understand how these students are now being served under Student Affairs, which is where the people, the programming, and the funding mainly went.

“Where are the programs? Where are the numbers? I think it's probably fair to say we're in a state of evolution where we're not entirely sure where these programs are and how they're doing, but I think it's fair to say that the heart of the ideas is still present,” he said.

Bouchelle wrote to WHQR, “There is no official documentation or current data on the student success and resource centers. Student Affairs is in the process of establishing structured processes for collecting and analyzing data related to measurable outcomes and student success.”

However, in the August compliance report, UNCW wrote that this implementation plan would begin in the 2025-2026 academic year. Key metrics would include “student participation, program effectiveness, student satisfaction, sense of belonging, retention, and persistence.”

The latest compliance report said UNCW was also looking into changing the name of “Living in Our Diverse Nation,” a degree requirement that can be satisfied by taking three hours of coursework from among dozens of eligible classes across various disciplines.

It noted that this category and the word diverse itself “may create confusion, the requirement itself does not compel students to adopt a particular ideology.” Bouchelle said this is “still under review.”

WHQR reached out to the university several times to schedule an interview. They declined.

We also didn’t receive any response from current staff leaders at Upperman, Centro Hispano, the Mohin-Scholz LGBTQIA Resource, or Asian American Cultural Centers.

*Editor's note: this article originally referred to the center leaders as faculty. They are technically "staff."

Related reporting

- Trustee Dr. Jimmy Tate shares some insights on UNCW's 'Equality Policy Certification' subcommittee

- In North Carolina, It's Do or DEI (The Assembly)

- UNCW faculty start an American Association of University Professors chapter

- UNCW's vice chancellor of student affairs discusses the impact of removing DEI from campus

- Black Student Union protests UNCW's response to mandated DEI removal

- The awkward, quiet death of UNCW's Razor Walker Award