WHQR's Sunday Edition is a free weekly newsletter delivered every Sunday morning. You can sign up for Sunday Edition here.

Earlier this summer, Wilmington City Councilman Luke Waddell proposed what’s been called a ‘camping ban,’ an ordinance that would create low-level criminal penalties for sleeping on city property, including surface parking lots (whether in a vehicle or not), as well as a host of other issues already covered by existing ordinances and laws.

The ordinance was a response to public concern over the increasingly visible presence of chronically homeless people in downtown Wilmington, including acute pressure from downtown businesses. Some of those business owners shared their concerns with Waddell through Wilmington Downtown Inc., where he sits on the executive committee, as well as online and at an early August city council meeting.

Waddell previously introduced a similar ordinance last year, but it was tabled as Wilmington — and many other municipalities — waited on the Supreme Court to settle the question of whether it is, essentially, cruel and unusual to move people off of public property without offering them someplace else to go. The court ruled it was not. And, while the court now leans distinctly to the right, liberal and conservative city and town governments around the country have cited the ruling to implement new local laws.

But that doesn’t mean there haven’t been objections — including those around North Carolina, which my colleague Kelly Kenoyer reported on earlier this year — and Waddell’s ordinance has certainly drawn pushback.

There’s plenty to debate and discuss when it comes to homelessness: what are the underlying causes, what are the best solutions, and who should take the lead — and foot the bill? In this week’s edition, I’ll get into all of that.

There’s also plenty of partisan political rhetoric that’s been, well, less than helpful. We’ve seen Waddell and some downtown business owners demonized as cruel and, yes, even fascist. We’ve heard Democrats mocked as weak and soft on crime (even ‘pro-crime,’ as some pundits have put it). And we’ve seen service providers caught in the middle, implicitly — and sometimes explicitly — blamed for failing to ‘solve’ homelessness, one of the most intractable and widespread social ills in our country. And that’s not even getting to the underlying issues that will continue to push more people into homelessness in the future.

I might lose some of you on both ends of the political spectrum here but, based on my conversations, Waddell’s ordinance would in practice be neither as evil as his critics claim or as useful as his supporters suggest. Some will call that ‘both-sideism’ — but I’ll hope you’ll at least read this whole column before you send the hate mail.

Waddell has said he feels the ordinance is a necessary step to address the homelessness issue in Wilmington, and told me he believes it would have a “broken windows” effect on other downtown problems (based on the theory that low-level ‘order-maintenance policing’ can have a positive domino effect, ultimately reducing more serious violent crime).

He’s also freely admitted his proposal is not a “silver bullet,” but a good starting point. And, he recently told me, he was both surprised at — and in a way happy about — how much conversation his ordinance has kicked off.

It’s clear there are passionate disagreements, and I would add that much of the conversation has been focused on people living and panhandling on the streets of downtown — who are an incomplete representation of the larger problem of homelessness. But we are talking about it, and that I’d argue is a good thing, provided the conversation can stay sane and earnest.

I think there is one grim point of agreement, however, and that is that what we’re doing right now is not working. As I have noted elsewhere — and I’m far from alone in doing so — we are in year seventeen of the Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness, launched in 2008. The plan reduced homelessness by 50% at one point, but Florence and Covid provided challenges — as did reaching the most vulnerable and chronically homeless.

That doesn’t mean people aren’t working hard, that there aren’t people who have dedicated years — even decades — doing good work. There definitely are. But those people are often treating symptoms, not root causes. It’s triage, sometimes, Band-Aids on bullet wounds. What would it look like to do better? And is there the political and financial will to do so? That’s what we need to hash out.

To do that, I think we need to look at the ordinance, the role of law enforcement, the homeless problem (and the people we’re actually talking about when we say that), the role of service providers, and what some of the missing pieces of this frustrating and tragic puzzle might be.

The ordinance itself

Before we go any further, let’s just lay out what the ordinance proposed by Waddell would do. In short, it would ban the following:

(a) Occupy, camp, sleep, or place, erect, or utilize any tents, cooking equipment, or bedding between the hours of 10:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m., or such other times as prohibited by signage, rule, policy, regulation, or law; and,

(b) Personal effects, including, but not limited to, clothing, food, bedding, or eating equipment, shall not be left unattended; for health and safety reasons, any personal effects left unattended pursuant to this section may be deemed abandoned and forfeited to the city for disposal at its election; and,

(c) City parking deck(s) and surface parking lots are for parking and associated activities; therefore, other uses are prohibited; and,

(d) Entrances to city facilities and associated areas are for ingress and egress to city facilities; therefore, other uses are prohibited;

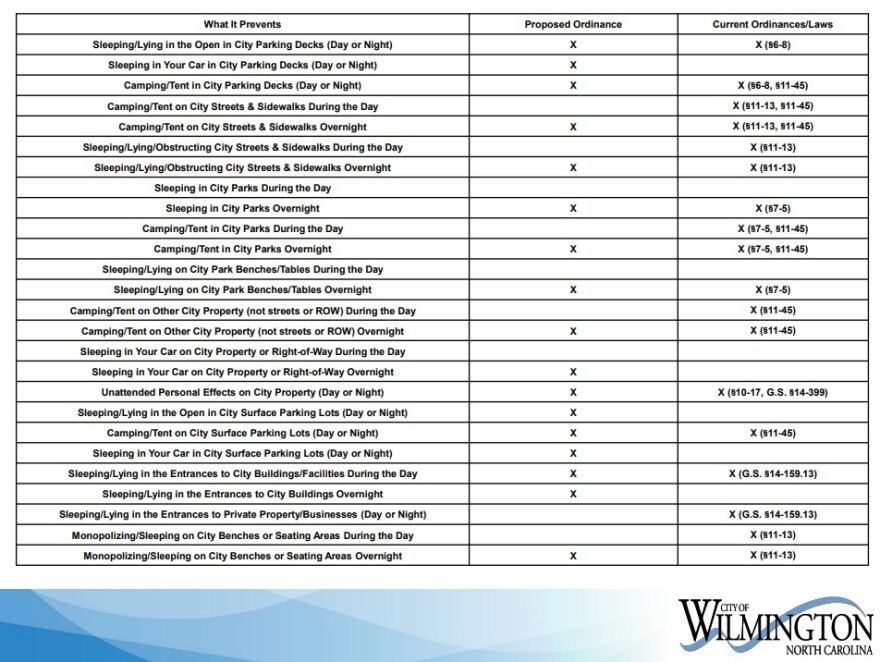

As indicated in the chart above, some of these things were already prohibited by existing statutes and local ordinances.

Notably, in North Carolina, municipalities are only authorized to create Class III misdemeanors, the lowest level of chargeable offense above an infraction. In North Carolina, judges get some latitude for sentencing –—but within structured guidelines. The most severe possible sentence for this type of misdemeanor would be 20 days in jail, but only with aggravated circumstances.

For Class III misdemeanors, first offenses can result in up to 10 days of community punishment — meaning supervised or unsupervised probation, or a fine. For those with up to four prior convictions (not charges), judges can impose up to 15 days of community punishment, or what’s known as intermediate punishment, things like special probation, residential program, electronic house arrest, intensive supervision, day reporting center, and drug treatment court. And for the highest level of prior convictions — five or more — a judge could impose up to 20 days of community, intermediate, or active punishment (i.e., incarceration, likely at the local detention center).

Many of the worst-case interactions with homeless people that have been shared — either anecdotally or as one of the video clips that Waddell shared during the early August council meeting — would likely be charged as more serious offenses: assault with a deadly weapon, breaking and entering, public indecency involving a minor, and so on.

The ordinance also doesn’t mean automatic arrests: officers can both interpret what terms and phrases like “occupy,” “camp,” and “left unattended” mean and decide whether to issue a warning, a citation, or a simple word of advice. And yes, that makes room for both abusive overenforcement and compassionate discretion.

So, that’s what the ordinance prohibits and what, in theory, the criminal repercussions could be — although, in practice, both law enforcement and prosecutors said it’s unlikely they would frequently arrest or prosecute people under what’s new in the law. And, we’ll get into that — and where the criminal justice system might play a different kind of role in addressing the situation.

But first, I want to touch on the complaints and concerns behind the ordinance (and the reason we’re having the current conversation).

Downtown business concerns

Homelessness is a perennial problem, but the recent push to address the issue has come, in large part, from concerns about how it’s impacting downtown businesses.

For some, this is part of broader concerns, including underage drinking (and teenage patrons of 18-and-up establishments), gun violence, belligerently drunk Marines, and other downtown issues that have been around since I got my first Wilmington job as a line cook at Front Street Brewery in 2003, and from what I’ve heard, long before that.

A few business owners actually thought Waddell’s ordinance and the subsequent media coverage were exaggerated for political points and ‘clicks,’ with one business owner calling it a “manufactured crisis” that was doing more damage than unhoused people. But for many others, homelessness has been a top concern as the most consistent and visible issue.

I know plenty of downtown business owners, employees, and patrons who have had scary interactions with people who are dangerously intoxicated or mentally unwell. (And, full disclosure, so have I.) And the point many downtown folks are making is that it does not take a lot of bad scenes to hurt business. Some of those people have lived through past periods of bad PR — due to real, exaggerated, or imagined spikes in crime and homelessness — and aren’t eager to repeat them. And these days, with more options around the region, like Porters Neck, Barclay Pointe, the Cargo District, and Mayfaire, there’s increased competition to further turn the screw.

Customers can be fickle. It doesn’t take much to dissuade them from going to a particular restaurant, for example: a slow service, a hair in their food, a slight uptick in parking fees. Ditto for downtown in general. On social media, I’ve seen people cite their reasons for avoiding downtown: getting harassed for money on the way from the parking deck, walking past someone who was urinating or defecating, or just not wanting to see a homeless person with their belongings stacked around them.

As I’ve written elsewhere, in a perfect world, you’d have patrons who were much more empathetic – and also much less skittish. In New York City, where I lived for almost a decade, people quickly developed the ability to tune out homelessness. Someone wrapped in blankets and cardboard, sitting on an air grate, would never dissuade customers from a restaurant, even if they were feet from the door. The ability of New Yorkers to filter out human suffering was almost sociopathic — I should know, I was one of them. So I’m not going to spend much time on my soapbox here, because I’d be a raging hypocrite.

I will say, many of the downtown business people I talk to care deeply about the people who are struggling with homelessness, some donate to nonprofits or volunteer at shelters or soup kitchens, others have explicitly asked the city and county to do more. But when it comes to customers, many literally can’t afford to judge. You can mock or chastise, but if a single bad experience has patrons clutching their pearls and venting on Facebook, that’s an empty seat during service, and a hole in the budget.

As one chef bluntly told me, “I need Landfall people to come downtown. This isn’t fucking helping.”

Some of the downtown business owners and managers have been pilloried as ‘heartless’ for framing things in terms of dollars and cents – but it’s worth remembering a lot of these businesses operate on very slim margins. Losing business means laying people off, or closing up shop. There are very real consequences for people — i.e service industry workers — who are already living financially precarious lives. Bartenders and line cooks don’t get severance packages; they don’t have 401ks.

As political as this issue has become, for most of the business owners I talked to, it’s not a partisan thing. Some are liberal, some conservative, some would tell you they don’t have time for politics. I don’t think most are wedded to any particular approach — but almost all are asking Waddell, city council, the county, anyone, to do something.

That something, though, is unlikely to be a lot more arrests.

Law and Order

The official party line, from interim Police Chief Ralph Evangelous, is that Waddell’s ordinance is “another tool in the toolbox” for officers, but not a quick fix. Incoming chief Ryan Zuidema, who is leaving Lynchburg, Virginia, to lead WPD starting in late September, is likely to say something similar. It’s a kind of conventional wisdom for police departments that, since officers have the discretion whether or not to enforce low-level offences, there’s really no harm in having more options.

I’ve talked in passing with officers on the street about the issue, but I also spoke with several higher-ranking Wilmington Police Department officers on background, and they all shared similar sentiments about the ordinance. Officially, they’ll tell you their job is to follow the policy set by the chief and the city. But, personally, most felt the ordinance wouldn’t change the equation much on a day-to-day basis.

They did say that it could be helpful to have a single ordinance with all the regulations pertaining to homelessness, something that officers might be able to easily memorize, without having to go through dozens of separate lines in the city code (one officer half-jokingly suggested they could laminate an omnibus ordinance and hand it out to new recruits).

Basically, officers told me when it comes to the general presence of unhoused people during the day — “ambient homelessness,” as one put it — there are no laws being broken. Panhandling, while a common complaint for patrons and business owners alike, is also legal, as a form of protected speech. Back in 2022, the city actually had to revise its panhandling ordinance, which can only be enforced if there’s a safety issue — which, at that point, would likely be a chargeable assault or communicating threats offense — or if there’s aggressive panhandling near an ATM.

Officers also told me they feel the public has a distorted perception of what would happen if they ramped up enforcement under city ordinances.

“We’re not taking them to jail. We’re handing them a paper ticket, a citation, with a date on it, that’s a few months out, maybe more — and, are they even going to remember that date? And are they going to show up in court? And if they do, in most cases, it’s a fine or probation and at most, maybe a few days, a week, in jail. At most. So then they’re right back on the street,” one officer told me.

A WPD lieutenant confirmed that a lot of what’s already on the books, both ordinances and state law, “goes absolutely nowhere when it hits the courtroom.”

Even the most visibly chronic homeless people downtown aren’t breaking the law. Most WPD officers know worst cases by name, and have for years. One WPD captain told me one of the only times he’d actually arrested one of downtown’s most chronically homeless men and taken him to jail was to get him sheltered ahead of a storm that was set to make landfall.

Some officers told me they worried about being taxed with additional workload, given that the department is struggling with dozens of unfilled positions. Others told me they didn’t mind working with social workers, helping to navigate homeless people to service providers, but they were concerned about being used as a replacement for trained mental health professionals.

“We have some training on how to deal with things, but it’s limited — it’s not what we do,” one told me.

While Waddell and Evangelous have both leaned into the “tool in the toolbox” metaphor, some officers are worried that the message is getting lost in the public conversation. On social media, Waddell’s fellow Republican officials and conservative residents have called for the ordinance to pass so it can ‘clean up downtown.’ A WPD captain told me he was worried that, whatever the chief or city council provides in terms of nuance, if the public expects the ordinance to ‘solve’ the downtown homeless problem, it will fall back on WPD and its officers when the ordinance fails to do so.

A couple of weeks ago, I spent about an hour with Republican District Attorney Jason Smith, who agreed with much of what I’d heard from the officers. He also told me he’d heard the same concerns from business owners that I had — and acknowledged some of the same limitations, in terms of enforcement, that officers had described to me.

“Well, obviously, we want to see streets that are clean. We don't like the visibility of seeing someone laying down, out in the middle of the day. It's not good. It's not good for our city. It's not good for our area. But as the enforcer of a law, is it illegal? Sometimes it's not, right? You sit on a park bench and you're homeless and you look homeless, that's not illegal,” Smith told me.

Smith said he was concerned about the real dangers — to the public and more importantly homeless people — of encampments, and said legal tools to break those up were useful. But he was skeptical of trying to use the criminal justice system to ‘clean up’ the downtown streets when it came to homelessness.

He spoke highly of WPD’s work, but noted that, “there’s a lot that goes on in this city that they have to respond to every day, whether it’s people getting hit by cars, drugs, murders, shootings, ATVs going crazy. They are patrolling downtown, them and the Sheriff’s Office, they provide a task force. But good Lord, if you’re going to come down here and you’re going to every [homeless] person and saying, ‘it’s time to move along,’ and you have to issue a citation and that takes time, it takes away from the rest of your patrolling.”

Smith was adamant that, “we’re not going to arrest our way out of this,” comparing the situation to the War on Drugs (drugs won, we both agreed).

And, like the officers I talked to, Smith noted that even a repeat offender with five convictions — not charges, but convictions — would get a maximum of 20 days in jail, which he said was both judicially improbable and financially irresponsible.

“Is a judge really gonna sentence a guy to jail for sleeping on the sidewalk? The answer is, 'no,'” Smith said. “Should we, as taxpayers, that's $100 a day, pay for that?”

Like officers and service providers I’ve spoken with, Smith said he felt like Wilmington’s homeless problem was in large part a mental health problem — part of a national issue that he said drove a lot of the crimes being prosecuted in his office.

One place Smith said he did think the criminal justice system could help address the problem would be with a specialty court for homeless people, similar to those for veterans, people dealing with drugs and mental health issues, and women who are pregnant or have young children. (My colleague Kelly Kenoyer took a deep dive into how some homeless people are already navigating these courts on an episode of The Newsroom last year; it’s really worth a listen, but you can also find a shorter conversation about it here, as well)

Defendants have to voluntarily agree to participate in these courts, but once they do, judges can divert them away from incarceration and towards rehabilitative services. A ‘compassionate court,’ as they’re sometimes called, for homelessness would share some features of a drug or mental health courts, but also offer some specific services tailored for unhoused people.

Smith said former District Attorney Ben David had been considering the idea before his retirement, and that he’d be willing to revisit it.

“I have thought about that, I’ve talked to some of my staff about it. We've got to get buy-in from people,” Smith said, meaning law enforcement, service providers, the public defender’s office, prosecutors, the probation office, and a judge to oversee the proceedings. (In particular, probation plays a major role in diversion, Smith said.)

The court would not be for everyone. Violent offenders wouldn’t be eligible, and homeless people who’ve rejected help in the past — either because they were distrustful or weren’t thinking clearly due to substance abuse or mental illness — might not agree to participate. Still, for some people, it might be very beneficial. The particular mix of carrot and stick available to a judge in these compassionate courts has proven very effective for other high-risk populations.

But, of course, the courts would ultimately only be as good as the resources that people can be connected to. More on that, in a minute.

What do we mean when we say ‘the homeless'

Most of the concerns — and complaints — about downtown fall into two categories. One is just the presence of homeless people, the vast majority of whom are not breaking the law or actively harassing anyone. The other is about more aggressive or visibly dysfunctional people, who may or may not be breaking the law, but are the source of a lot of the ‘negative interactions’ reported by downtown businesses, patrons, and residents.

But these people, the visibly homeless of downtown Wilmington, represent a fraction of the problem. And, even assuming that Waddell’s ordinance works, and granting that there are knock-on impacts on the downtown environment, there’s still a much bigger issue. So, if the goal is to have a conversation, it’s worth trying to get the whole thing in the frame.

Talking to service providers, downtown business owners, law enforcement, prosecutors, and even other homeless people, there are about two dozen people downtown who are the most chronically and intractably homeless.

Some have serious mental health issues, substance abuse problems, or both — what’s known as co-occurring or dual diagnoses, which can be difficult to handle. That’s not just because they exacerbate each other, but many service providers focus on either mental health or abuse, but not both. (There are more options for substance abuse than mental health, more on that later.)

Because they are essentially living in extremis —around the clock, everyday — they’re not always reliable narrators of their own conditions. But from the more lucid conversations I’ve had, many of them have been homeless for a long time, sometimes with brief periods of shelter of one type or another. They’ve often alienated or been abandoned by family and friends. Most often, the people who know them best and look after them are cops and service providers. When elected officials and other stakeholders talk about people who ‘refuse’ services or seem to be unreachable, it’s often one of these folks.

These are human beings, but many have fallen into a de facto untouchable class. Those with most serious mental health issues aren’t unsalvageable, but the resources — the time, money, professional and familial support — necessary to get them some semblance of safety, stability, and sanity would be exceptional. It is more than our current network of service providers often has at their disposal.

Both service providers and law enforcement officers noted that, three generations ago, these people would have been institutionalized in state mental hospitals. Those facilities were shuttered in the two decades after WWII, and for good reasons, but the ensuing shift of mental care to regional and local community-based programs left most areas without the kind of subsidized, around-the-clock care that’s needed. Right now, the most extreme cases might go to New Hanover Regional Medical Center, but that’s acute care — so, sooner rather than later, patients are discharged back onto the streets.

For a lot of reasons, including intoxication and mental illness, but also an earned distrust from bad experiences with law enforcement, hospitals, or other agencies in the past, it can be hard to get some of these people to accept help. And a small number of homeless people have simply decided to live their lives this way, a decision that they might make differently if they were sober and in substance or mental health treatment, but that seems final if you’re just having a passing conversation with them.

Sometimes officials and stakeholders use this small group of very unfortunate people as a metonym for homelessness writ large — and the difficulty, perhaps impossibility, of fully rehabilitating them is used as a license to throw one's hands up and say ‘they won’t accept help’ or even ‘they can’t be helped.’ I’ve heard darker suggestions, too: rounding them up to be shipped off (to where?) or arrested (and then what?).

But there are many other types of people who are homeless — and their homelessness can look like a lot of things.

There are over 200 homeless people in New Hanover County living in some kind of shelter — I don’t mean like a tent or car, but a friend’s spare room, or a motel, or an emergency shelter like Good Shepherd (which serves over 100 people) and similar but smaller facilities. It’s not uncommon for folks to cycle between different places, renting a room when they can, crashing on a couch until patience and goodwill runs out, and staying at a shelter when there’s room (and the region is way over capacity).

There’s not one story here. Some might be on a street corner with a cardboard sign, but a lot of these folks still have one foot in the world many of us would recognize: they have cars, shop for food, work a variety of jobs, have kids and families. I once worked in a kitchen with a line cook who was homeless for six months and never said a word about it until he asked me to help him move some hand-me-down furniture into his new place — I’d had no idea. It’s hard to generalize, but many people dealing with this type of situation aren’t exactly invisible, you just don’t know that’s what you’re looking at.

And, while substance use and mental health play a role here, I’d say it’s not too different than the role it plays with housed, fully-employed people. But if you have anxiety, or maybe drink too much, that’s going to get amplified if you don’t have a home (if you’ve ever been homeless, say couch surfing for a few weeks, you know the feeling of not having your own space — and what it does to your mental health and sense of self-worth).

Most of the people in this large, diverse category struggle with housing affordability. There are a lot of people living just a few paychecks away from foreclosure or eviction. It’s happened to me, maybe it’s happened to you. I was lucky enough to have family and friends to lean on. Not everyone is.

The refrain of ‘they won’t accept help,’ that really doesn’t apply here, according to service providers. These people would, overwhelmingly, accept a bed to sleep in, a path housing, in a heartbeat.

Then there are the unsheltered homeless — that’s at least 230 people in New Hanover County, 30 or more in Brunswick and Pender counties (and those numbers could well be higher). And again, there’s no one story about that group of people. Last year, WHQR profiled five people dealing with homelessness, and each person had their own trajectory and issues.

Some are living in vehicles — and would be affected by bans on sleeping in those vehicles on city surface lots — others in encampments under overpasses, along railways, or in wooded areas. Many have some friends or family they can occasionally rely on for help, and some still work, albeit at some of the region’s lowest-paying and most menial jobs. Some are families, or couples, or living alone. Some use substances, but that can mean drinking a few beers or abusing hard drugs — which hardly seem like they should fall in the same category. Some end up dipping into homelessness during a rough patch and spend just a few weeks or months on the street — some have been homeless for much longer.

For reasons I think any empathetic person could imagine, living unsheltered can be a kind of quicksand. Your ability to maintain your connections, personal hygiene, a sense of stability and sobriety, it can all get eroded, quickly or slowly, by living rough. I don’t want to try to paint too broad a picture by anecdote, but I’ve definitely heard stories from people who, bit by bit, habituated to circumstances they might have recoiled from on day one.

But a lot of these people can — and are — helped. And it’s sometimes difficult to say what, exactly, ‘winning’ the battle against homelessness would look like.

Measuring and managing homelessness

The official numbers provide an admittedly muddy picture of what’s going on. And that means the numbers can be used to claim victory or defeat when neither is really accurate.

When officials do a Point in Time count, it’s a snapshot. For one, it’s in January, when people might spend their limited financial resources to get shelter, or are sometimes allowed inside by family and friends because of the cold — an understandable desperation or kindness that skews the numbers of how many people are living rough outside. During a recent Wilmington City Council meeting, Republican Councilman Charlie Rivenbark — who has watched the city struggle with homelessness for decades — noted this, and staff suggested they could do a summertime count to get a more well-rounded picture.

These PIT numbers also don’t really capture trajectories: some people are clawing their way out of homelessness, others are sinking down into it.

And, the official definitions obscure part of the problem. Of the roughly 500 or so homeless people in the Cape Fear Region, around 165 are ‘chronically homeless,’ meaning they have a disability and have been homeless for at least a year (or experienced three episodes of homelessness over four years). But that fails to capture people who don’t have a disability but have been homeless for a long time, or who have repeatedly fallen into homelessness.

That’s the story in Bergen County, New Jersey. It’s an affluent region, sitting across the Hudson River from the Upper West Side, the Bronx, and Westchester. Geographically, it’s only slightly larger than New Hanover County, but it has over four times the population. According to Community Solutions, a nonprofit working to end homelessness, in 2016 Bergen County became the first community in the country to end chronic homelessness.

Bergen County’s efforts are genuinely impressive, marshalling significant resources under a single, focused office that brought together government and nonprofits. But there are still many people who have been homeless repeatedly or for more than a year. The urban affairs nonprofit and magazine Next City wrote about this several years ago, and helped tease out another issue as well: ‘functional zero’ measures of ending homelessness can obscure the underlying problems that cause homelessness in the first place.

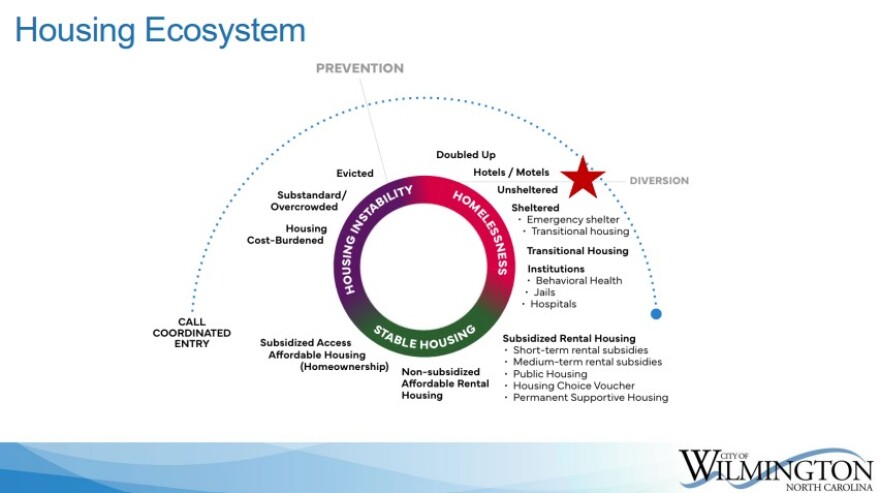

Right now, a lot of the work — good and important work — that’s being done in Wilmington and the Cape Fear Region is providing shelter. That includes over ten providers offering emergency shelter and another ten offering transitional or permanent supportive housing, which is subsidized and includes wrap-around social services.

All of these shelters are at or over capacity. Even with the completion of the new Salvation Army facility located north of Creekwood off the MLK Jr. Parkway, there will be around 230 or so beds in our region — far short of the roughly 500 homeless people documented in the Cape Fear Region during that last PIT count (which, again, may have missed people). As many as 200 will still be on waiting lists, so to speak, for shelter, even after the Salvation Army facility comes online.

In addition to a gap of hundreds of emergency shelter beds, according to an analysis by city staff, presented by Housing and Neighborhood Services Director Rachel Schuler during the recent special meeting, the region is also short between 25 and 75 permanent supportive housing units. These are the most expensive projects, and they’ve received pushback from conservatives, based on objections to Housing First policies.

But there’s an even larger gap: 800 units for what’s known as Rapid Rehousing and Access to Affordable Housing. These are units for people who have the will and the means to get back into a home — if only there were an affordable place to go.

At the moment, there’s an understandable focus on getting more shelter capacity — with affordable housing as a kind of ‘next step.’ And there’s more that the local government — the city and county — could do, along with the state and federal partners. And, of course, there’s The Endowment (you know, the $1.6 billion elephant in the fiscal room, born from the sale of the hospital, tasked with making transformational grants, essentially for the exclusive benefit of New Hanover County residents).

Who takes up the mantle, and foots the bill, has always been a negotiation. Right now, it’s a fairly tense one.

City and County (and The Endowment, and Trillium)

Over the last month, there’s been a lot of finger-pointing, including between the city and New Hanover County (the two’s on-again, off-again relationship when it comes to cooperating on housing, transportation, and other issues is the stuff of governmental tragicomedy).

City attorney Meredith Everhart appeared to have kicked off the latest round of recriminations when she told council in early August they were “having some difficulty” with the county-funded social workers who partner with WPD officers as part of the Getting Home project. That’s a city-county program, founded in 2022 as the county considered its own ordinance to restrict homeless people from county property, particularly the downtown library and parking deck. Everhart’s comments sparked a flurry of concerned emails and ultimately a meeting between county staff and Evangelous and WPD brass to “reaffirm” the partnership (WPD reportedly apologized for the miscommunication). The reality ended up being that social workers are spending less time in the field because they now have fairly full case management schedules — not because they’ve in any way bailed on the project. (Although it does beg the question of whether there ought to perhaps be additional social workers added to the program.)

But there have been other suggestions, by Mayor Bill Saffo and Councilwoman Salette Andrews, both Democrats, that the city is increasingly ‘going it alone.’ And, because — at least anecdotally — there’s some regional migration to the shelters and services provided in Wilmington, officials have argued that the city isn’t just pulling its own weight, it's pulling others’ as well.

At Saffo’s request, staff added up the city’s contributions to homeless services over the last five years, which totals around $5.5 million, with the majority (over $3 million) going to Good Shepherd. That’s been contrasted by Andrews and others with the county’s recent fiscal cutbacks (in many cases, as Covid-era federal funding dried up and the county declined to pick up those line items).

To that end, Andrews said she’s asked city staff to prepare a grant request for The Endowment to fund a strategy worked out by city and county officials and staff last year. As detailed in a Substack post this weekend, Andrews said the proposed grant would help expand service provider capacity, adding more low-barrier shelters (especially those offering showers, laundry, and other hygiene amenities), housing assistance, and a mental-health day center. One would hope that, with a strategy and a team of partners in hand, the city could make a good case to The Endowment — and if Endowment leaders were to say no, I think the community could rightfully demand a damn good explanation.

All that said, I think the Manichean city vs. county picture that some are painting isn’t quite accurate.

It’s true that the county has divested itself from nonprofit funding (foisting $1.6 million in vetted grants to The Endowment for this year, with a question mark hanging over future years), and recently left the city-council housing committee after ending its five-year, $15 million affordable housing program after three years. The county also cut roughly $27,000 in funding for the Continuum of Care, the federally mandated organization that distributes federal grants and runs the coordinated entry program for homeless people (the county has noted that the CoC did receive a $200,000 grant from The Endowment).

These decisions, part of this year’s efforts by Republican commissioners to trim the budget, have left a bad taste in a lot of mouths left of center — but the county has continued to fund a host of projects related to homelessness, including $536,000 this year for the Getting Home program, and $500,000 over two years for the Salvation Army facility.

The county has also dedicated millions of dollars, including Opioid Settlement Funds, to address mental health and substance abuse, including debt service and operational funding for The Healing Place, which provides both emergency shelter and peer-led substance abuse treatment, and roughly $1.5 million for the 36-bed STAR detox facility (which replaced The Harbor, a crucial resource for uninsured and underinsured people). While that’s not exactly the same as directly addressing homelessness through additional shelters or supportive housing, I think some experts would agree it’s part of the bigger picture of the homeless problem.

But for me, the most interesting county contribution to the problem has been percolating under the radar: a staff-led proposal to build a residential mental health facility that would offer medium-term inpatient care. The proposal is modeled on The Healing Place, a partnership with Trillium, the quasi-governmental agency that directs state and federal funding for mental and behavioral health issues.

County staff are currently looking at two facilities for best practices: HopeWay, in Charlotte, and Skyland Trail, in Atlanta, Georgia (Hopeway is itself based on Skyland Trail’s model). Staff visited Hopeway and, according to a county spokesperson, they’re planning to revisit a trip to Skyland in the fall.

Chief of Strategy and Innovation Cindy Ehlers confirmed Trillium was “excited to work with the county on this first of its kind project for adults who experience mental health concerns and need long term support and sometimes transitional housing in our state,” and was in the process of setting up a meeting with the county to “get more into the details.”

I spoke with Beth Finnerty, who was the founding executive director for Skyland Trail thirty-six years ago and now serves as President and CEO.

She told me Skyland started as something of an anomaly — "When we opened under 36 years ago, we were one of very few, and insurance companies didn't know what to do with these residential programs," she said.

Skyland Trail now has over 100 beds spread across several campuses, providing a crucial form of treatment between acute care — say a three-to-five-day involuntary commitment or hospital stay where someone gets stabilized — and longer-term outpatient psychiatric care. Importantly, the facilities also offer services for dual-diagnosis patients who are dealing with mental health and substance issues.

Finnerty noted that, over the years, there have been major sea changes in the stigma around mental health. Part of that is reflected in attitudes towards the location of the campuses; what once might have been a source of NIMBY pushback hasn't had a negative impact on property values or public opinion, Finnerty said. She added that neighbors frequently become volunteers and that community groups use the facility's auditorium for events.

"I mean, our facilities are beautiful," Finnerty said. "Property values have increased."

She also cited the passage of the Affordable Care Act as a significant benefit for mental health care; the ACA helps cover inpatient care and strengthened ‘parity laws,’ which essentially require insurers to cover mental health and substance use issues on the same terms as medical and surgical benefits.

But, as Finnerty noted, ACA and other insurers frequently fall short of covering the average three-month stay that Skyland offers. She said 45 days was the most she’d seen covered, just half of what many patients need before they’re ready to transition to outpatient or day center care. And that care can be expensive, well over $1,000 a day for inpatient, $500 a day for intensive outpatient, when you add in the cost of medication and psychiatric or other therapeutic care.

“The downside is that it runs out pretty quickly, and that's when our financial aid kicks in, and it allows them to complete their services here, because it doesn't happen overnight,” Finnerty told me. “So we raise money from the Atlanta community, and we base our financial aid program on the federal poverty guidelines, and it's pretty transparent for our families to see what they can get. It's based upon household income and size, and it's just been a lifeline for so many of the people that we're serving.”

To be clear, this project is in the very early days — but it is a real thing that can be done. Based on county emails and agenda meetings I’ve reviewed, there have even been some early conversations with The Endowment and other philanthropic community partners.

Working with Trillium could also help address the persistence argument that building more resources would have the negative side effect of drawing more homeless people, a feedback loop some conservatives have pointed to as a reason to stop the flow of 'unlimited' funding to service providers. Law enforcement officers I spoke to also frequently invoked this argument.

While CoC data shows the majority of homeless people in Wilmington are from here, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence (including my own reporting) that some came here originally to get treatment for substance abuse (both to get away from 'people, places, and things' in their hometown and because Wilmington has a lot of private treatment options, not to mention nice beaches). And Finnerty acknowledged that their Atlanta facilities pulled from other regions, especially those with poor mental health resources, like Texas.

But because Trillium is responsible for a wide portion of North Carolina, covering 46 counties, it might have more luck getting above the fray of arguing about paying for 'other regions' problems,' as I've heard it put. (And, in fact, The Healing Place currently contracts out its beds to many other eastern NC counties.)

In any case, addressing mental health and affordable housing are the closest I think we’ll get to addressing the root causes of homelessness, based on my conversations with just about everyone involved in this issue — including those who are themselves homeless.

During the city’s special meeting in mid-August, Councilman Rivenbark asked Hillary Faulk Vaughan, clinical director at Physician Alliance for Mental Health, “If you could snap your finger and solve the problem today, what would be the first thing?”

She responded, “I would say, it would need to be a combination of housing and greater access to stabilization in care, in residential or supervised settings,” noting that wouldn’t be for everyone. But many of the other service providers I spoke to agreed.

Short term, the region needs more emergency and supportive shelters, but long term, we have to address the reason people need those shelters.

It’s not an accident that these are too enormous and complicated issues. But I can say this, at a time when governments at every level are looking to trim their budgets, and we see less political will to leverage significant taxpayer money for the homeless, I think you could find broad consensus for the need for affordable housing and mental health care — not just for the most vulnerable among us, but for wide swaths of the population.

A few words about the costs of homelessness

There are moral, ethical, and scriptural arguments for focusing specifically on the most in need among us. There are also financial arguments, which tend to have a broader appeal. For politicians, journalists, and advocates alike, if you want to get the people's attention, aim for the pocketbook and the wallet.

That said, the financial situation is complicated — and I don't think slapdash math will win many over.

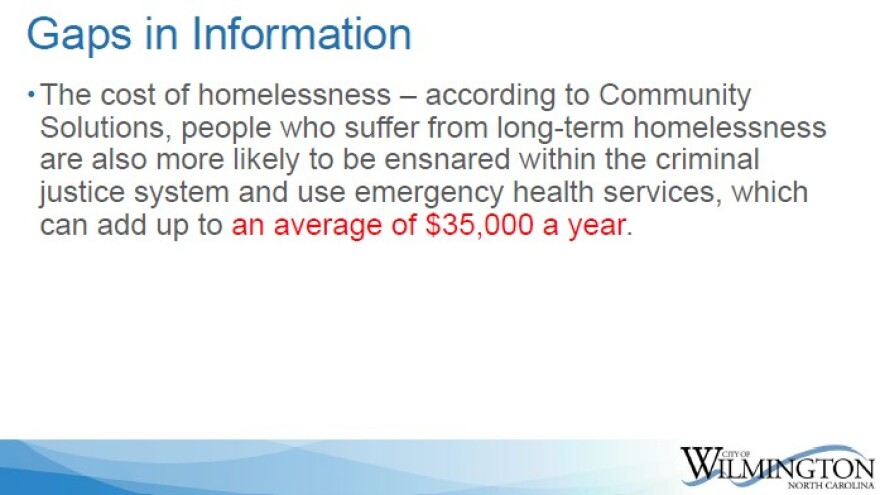

City staff and advocates have cited Community Solutions' estimate of the average cost of chronic homelessness. According to the nonprofit, "People who suffer from long-term homelessness are also more likely to be ensnared within the criminal justice system and use emergency health services, which can add up to an average of $35,000 a year."

Some, including Andrews, have just multiplied $35,000 by the number of unsheltered homeless, to get a $9.4 million price tag that "we're already paying," as Andrews put it.

I'll note that Community Solutions isn't super transparent about where that $35,000 figure comes from, although if you follow enough footnotes, you can find your way to a few studies that support similar costs. And, of course, it can be hard to get a really accurate number of how many people are suffering long-term homelessness.

But even accepting $35,000 per person and $9.4 million annually as fair estimates, things are still more complex.

Arrests are inexpensive in comparison to the costs of healthcare (you'd have to spend almost the entire year in the New Hanover County detention center to rack up $35,000, but I'm willing to bet you could rack that up in less than a week, with a number of health issues).

So, I think it's safe to say in our region the preponderance of the costs are coming from Medicaid and Medicare and also from New Hanover Regional Medical Center providing unreimbursed charity care — which, as a nonprofit, Novant writes off against its obligations to receive tax breaks. (Whether or not North Carolina's nonprofit hospitals actually do enough of this has been a long-running issue, and was a hobbyhorse for former Republican State Treasurer Dale Folwell.)

There's a profound difference between costs borne by the state (for Medicaid) and federal government and a nonprofit hospital network — plagued by allegations of excessive executive compensation (another Folwell hobbyhorse) — and those born by local taxpayers.

And, to that end, it's worth noting that this year's City of Wilmington budget negotiations did not contemplate any additional funding for day shelters or mental health, according to a city spokesperson. (Although that could change in November, when city council and staff will again sharpen their pencils and look ahead to the FY26-27 budget.)

I do think that the issues of charity care should bring Novant to the table. And I do think, as I've said, The Endowment would have to make a good case not to invest in a strategy to reduce homelessness. But both are more likely to be partners than sole funders, and if that's the case, they'll want to see something a bit more accurate than a back-of-the-napkin estimate if they’re calculating an ROI.

Rhetoric and Reason

As I’ve said, there’s been a lot of passionate debate about this issue — and some heated rhetoric, particularly from council members Waddell and Andrews. Both are smart, both care about the community, and both are politically ambitious — and have racked up points with their respective bases on this issue. Never let a good crisis go to waste, as the saying goes. But I would hate for the meaningful conversation that’s happening right now to get reduced to a political Punch and Judy show.

Did Waddell short-circuit some debate by calling his ordinance a binary choice and a “reasonable, common-sense” solution (implying that, if you disagree, you’re unreasonable and senseless)? Probably. It certainly seems to clash with his suggestion that he’s open to conversation. I asked him about this, and he stood by what he’d said.

Was it helpful for Andrews to implicitly compare the ordinance to the Nazi’s 1933 “Law Against Dangerous Habitual Criminals” on Facebook? I don’t think so. I asked Andrews about this, and she wrote back, “My post was a reminder that, as we tackle issues like homelessness and public safety, we must ensure our laws are fair, balanced, and protect everyone’s rights.”

But, at the same time, I think Andrews is right that — if you have nowhere to lay your head at night — then making it a crime, even a low-level one, is bound to feel like you’re very existence has been criminalized. In the Kafkaesque nightmare that homeless people endure, this has surely got to feel like a particularly dark twist. (But, by the same token, no one on council has made any effort to remove other ordinances that impact predominantly homeless people; aside from the adjustment to the panhandling ordinance over free speech concerns, the other ‘criminalizing’ statutes remain on the books.)

And, I think Waddell has a point when he complained about weak leadership. Whether or not you agree with his ordinance, and whether your concern is downtown aesthetics and business, the well-being of homeless people, or both, I think you have to acknowledge that we have extraordinary resources in our community and have failed to put together a more concerted effort to address homelessness. The fact that some elected officials are still saying they need more data and information is, well, kind of galling. I think certainly some service providers might feel that way.

“I mean, it's not like we're throwing good money after bad, but I've sat in so many meetings just like this,” Rivenbark said earlier this month, and not for the first time.

Almost ten years ago, about eight years into the Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness, one of my first editors was talking to me about a somewhat similar debate. Folks on the right were calling for ‘law and order’ while folks on the left called for compassion and more resources. He’d earned a fair amount of cynicism covering local politics for decades, and his outlook was pretty jaded.

“You’re gonna see a lot of this,” he told me. “Democrats promising shit they can’t afford and Republicans banning shit that’s already illegal.”

That’s a bit harsh, I know. But when I brought the quote up to non-politicians — meaning service providers, cops, advocates, and even homeless folks — there was frequently a smirk of recognition, a wry eyeroll and nod, and sometimes a cynical chuckle.

But in the war against homelessness, we can do better than trench humor, I think. No matter what happens with the ordinance, there is more work to do. I would love to see that be the topic of debate.

Below: Presentations on the proposed anti-camping ordinance and an update on the region's unsheltered population and services for the homeless.