Student crime data

While schools track the reasons students are suspended in-school (ISS) or out-of-school (OSS) for misbehavior, they also track more severe crimes.

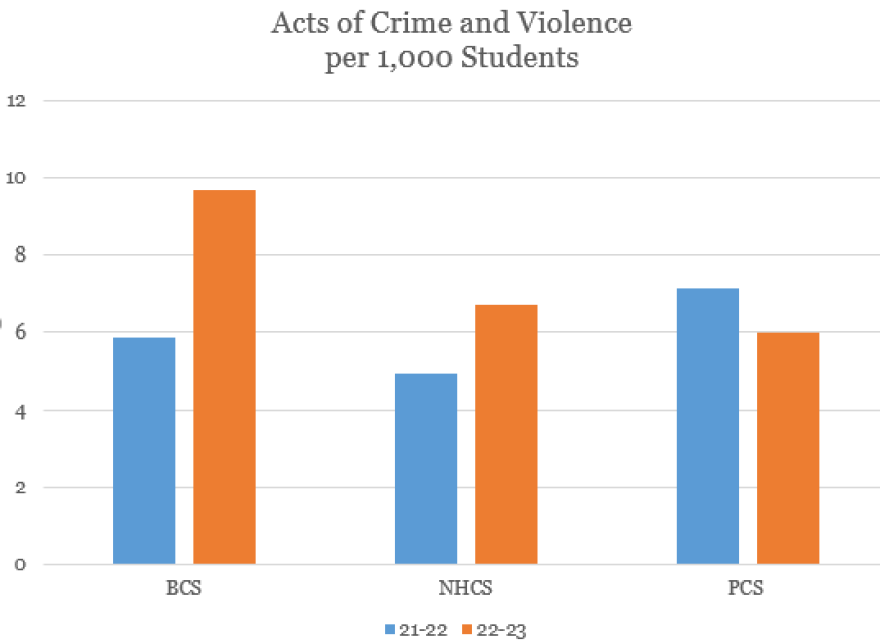

For the 2022-2023 school year, the number of criminal acts per one thousand students in New Hanover County Schools was higher than the previous year. The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) will release statistics for the last school year later this fall.

Brunswick County Schools saw higher rates than NHCS and Pender County Schools.

NCDPI tracks student crimes like assaults (for example, attacking school personnel), possession of weapons and/or drugs and alcohol, robberies, and sexual assaults. The most significant portion of crimes in schools are possession of controlled substances and alcohol.

Most (78%) of the 167 crimes reported in NHCS in 2022-2023 came from high schools. Far fewer came from middle school and elementary schools.

These rates are statistically low: 167 incidents among 24,796 NHCS students, with one in ten being physical or sexual assaults. Still, these events can leave an indelible mark on students and staff. Those negative experiences appear in ratings on a state survey and descriptions in a local NHCS one.

2024 NC Teacher Working Conditions Survey

NCDPI conducts a statewide Teacher Working Conditions survey every two years. About 91% of the district’s teachers and administrators took it this year.

Two categories in the survey featured questions about how teachers felt about student behavior: ‘managing student conduct’ and ‘safety and well-being.’

In New Hanover County, 57% of teachers said they felt students follow the rules for conduct, compared to 68% of teachers across the state. At NHCS, 65% agreed that school leadership routinely enforces the rules for conduct compared to 77% statewide.

According to survey results, the most significant student conduct issue for NHCS teachers is disrespect for teachers; 72% of NHCS teachers felt this way compared to 63% of teachers statewide. And 70% of NHCS teachers agree there are issues with ‘unstructured areas’ (hallways, cafeterias, bathrooms) in their schools, compared to the state average of 63%.

The other issues behind disrespect and unstructured areas were tardiness and skipping (district 65%, state 57%) and disorder in the classrooms (district 58%, state 51%).

One in four teachers say there’s an issue with threats of violence against them. The state average for this was roughly one in six. NHCS said physical violence between students is a problem more often than the state average: 52% at NHCS versus 43% statewide.

2024 NHCS Board Survey

Nearly 2,000 staff members answered the NHCS board survey. It opened in early May and closed by the end of the month.

The survey had a comment section dedicated to the question, “If you don’t feel supported, how can the BOE help with student discipline?” This question garnered 655 comments from teachers and staff.

In her July presentation on the results, board member Stephanie Walker said that the main themes from these comments were "the need for consequences, listening to teachers, spending time in schools, and creating consistent policies.”

WHQR’s analysis of the comments found that the top issue was the lack of consequences for students, followed by staff’s ire at the board for focusing on partisan matters (like the banning of Stamped in the district’s classrooms and the controversial classroom display policy) instead of supporting teachers with discipline and other student issues. They also mentioned they can’t effectively deal with behavior if support professionals like behavior specialists, multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) coordinators, social workers, and counselors are cut.

From the start of last school year (September 2023) to this upcoming one (July 2024), there are only three fewer MTSS coordinators (18 to 15 positions) and counselors (73 to 70). The district is down one (three to two positions) for behavior specialists. The district said they have one more pre-K/headstart behavior position for this age group.

Social workers are down five (44 to 39); however, this number could be even fewer as the year progresses, as acting superintendent Dr. Christopher Barnes said previously that they’re trying to get down to 25 social workers through attrition (meaning retirements or resignations).

Teachers and staff commented on the district's lack of accountability, suggesting that more stringent suspension policies should be resumed. Some said that students who continually cause physical harm to other students and staff should be moved to the district’s alternative schools, like J.C. Roe.

Setting expectations, clear consequences

Assistant Superintendent Julie Varnam said the policy 4300 series outlines how the district deals with student behavior—along with the district’s Code of Conduct. According to policy 4302, each school must have its own plan for student behavior.

“The reason it's important for each school to create that is because they can identify their own school's data, their own school's challenging behavior trends, their own school’s unique talents and skills in addressing challenging behaviors,” Varnam said. (*You can find the complete list of consequences at the end of this report)

The district relies on the STOIC framework, which stands for ‘structure-teach-observe-interact-correct.’

Varnam said this model addresses challenging behaviors before they become problematic and interfere with learning.

“And then also to carry out appropriate consequences consistently across the building because our goal in the classroom, of course, is to be instructive,” she said.

Varnam said relationship building is most important when establishing rewards and consequences in a classroom, as are clear routines and students' engagement in course content.

If the misbehavior turns into violence, Varnam said the district takes this dangerous or aggressive behavior seriously and that it “has to be addressed immediately.” However, reteaching and redirecting must occur even after immediate or long-term consequences are applied.

“So before we apply consequences, we have to really understand the culpability of that student in engaging in that behavior. Was it in self-protection? Was it to be aggressive? If the answer to that is different, we have to carry out a different level of intervention. So this is very complicated,” she said.

Essentially, the question for staff is: did the student have the knowledge and strategies to correct the behavior? If it were proven that the student did, then a more stringent consequence would be applied.

The schools are undoubtedly responsible for discipline and consequences with student behavior, but when North Carolina laws are broken, that leads to the New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office deputies.

School Resource Officers' role

There are School Resource Officers (SROs) stationed at every school in the county, including several at the high schools. The county’s total annual investment in these positions is $4.9 million (which includes salary and benefits), and the district typically pays the county back $403,000, which it receives from state grant funding.

New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office Lieutenant Jerry Brewer outlined the SROs’ purpose in the schools.

“It is not our role to be the disciplinarian at a school. That's the role of the school administration. Now, it’s when they cross that line of 'this is no longer school disciplinary,' [it’s] not necessarily a[n], ‘acting up in class’ type of thing,” he said.

Brewer said they start enforcing state laws mainly in middle and high schools, and statistics show that high schools are where more of these incidences occur.

“Some of these kids are big people. It's not up to the teacher to stop a fight. I think a lot of them get involved and help, but that's the reason they have the deputy there, and they have the training and the tools they need to break up a fight between two to four, even six people,” he said.

The typical arrests in high school are for either illegal drugs or fighting. Brewer said another factor that complicates the situation for SROs is overcrowding in high schools.

“Every single high school we have is overloaded. I mean, it's just a sheer number of people there,” he said.

While Hoggard, Laney, and Ashley are overcrowded, New Hanover High is under-enrolled.

Some critics say that the research on SRO impact shows mixed results — and that sometimes, at the middle and high school level, they can contribute to more student suspensions, expulsions, and arrests, especially for students of color.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and discipline

While Brewer said SROs have to enforce the law, he noted that the deputies are also trained to understand issues like the school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon. This is based on data showing that students who are suspended at higher rates are more likely to be arrested and jailed as adults — and this affects more students of color. Hence, some researchers say finding alternate consequences or rehabilitative strategies is better.

“[Kids] still haven't developed that part of their brain that says, ‘If I do this now, that's going to hurt me later;’ they just don't have that. So we're trying to have programs that can help them unmake a mistake without getting into the criminal justice system,” he said.

He also mentioned an example of a student’s impulsive decision that was unfortunate. It was at New Hanover High in May when a student posed in front of a mirror with a gun.

“It's an immediate, ‘Hey, let me do this. This will give me clicks. This will give me whatever.’ But it also got you arrested, straight to a felony, and that's an unfortunate reality of the world today. I mean, why bring a gun to school?” he said.

Some staff on the NHCS survey described incidents like students throwing chairs or destroying classrooms. While these may be anecdotal accounts, UNCW associate professor Dr. James Stocker said the district should pay attention to them.

Stocker, a special education expert who teaches courses in applied behavior analysis, including classroom management strategies, said teachers' accounts “should be absolutely supported and validated, and then also realize, what led that reaction to occur in the child, to understand maybe a little bit more why, and is there a strategy that might work a little bit better in that situation? And that's tough, right?”

Varnam also said that the district is not immune to stressors and crime in our community but that “Our schools are certainly among the safest public places you can find. I believe that, and when we have situations where our students, staff, or families do not feel safe, that needs to be immediately addressed.”

Brewer agrees. “I'd say our schools are not dangerous. The school is a microcosm of society. So, is a movie theater dangerous? No, it’s just when different violent acts get highlighted. [...] I think our schools are very safe, especially since Sheriff [Ed] McMahon put a deputy at every single school.”

Stocker said that students who get help from educators and support staff when it comes to addressing their ACEs will have much more success in middle and high school.

ACEs can range from having parents who are incarcerated, being homeless, and experiencing physical, emotional, and/or drug and alcohol abuse in the home. ACEs are often part of maladaptive behavior — and they can be difficult to deal with, even compounded, by the harsh economic realities parents face these days.

“It's even harder now to raise children than I believe it was in the past, just because of the amount that both parents need to work to make ends meet,” Stocker said.

Parental influences

Some staff respondents on the NHCS survey discussed having more parents involved in enforcing consequences for students who misbehave in school.

Brewer said he sees parental involvement as essential to whether or not students re-offend with more severe acts of violence and incidents involving drugs and alcohol.

“It’s whether or not you have parents involved in care, and some don't, and you see that same offender again and again. You know it's just unfortunate, but it's reality,” he said.

He gave a more concrete example, “[If] you're raising your kid that marijuana is not a big deal [like] ‘It's going to be legal here one day, and it's okay to have.’ ‘No it's not, and it's still illegal.’ And we get kids that bring in vape products to school, bringing edibles to school. I mean, it's a constant fight between the school administration and us; they bring our attention, and we have to deal with it.”

However, if the parent(s) or guardians can establish a good rapport with the school and the teacher, it will help with these discipline and behavior issues.

“One thing that I've learned is that the better our relationship with the parents, the easier my job was as a teacher,” Stocker said, reflecting on his early years as an educator.

Support staffing – who can respond?

While parental support is important, the district must also take care of students’ academics and well-being while in the building. According to Stocker, this becomes more difficult when staffing levels drop. If schools and teachers are dealing with challenging behaviors constantly, it’s hard to employ effective behavior-management strategies.

Another issue, he said, is the current levels of teacher attrition and the influx of staff without certifications or pre-service training. “And what occurs is they go in, and it turns out to be a revolving door where they're not making it.”

According to the district, 80 beginning teachers came in with alternative licensures for the 2022-2023 school year. This past year, that number rose to 88. For the upcoming one, they have 69 coming in.

Stocker said some are frustrated when they don’t get support or find the time to employ the right strategies.

“How do you expect me to teach when I'm constantly having to redirect or I'm constantly having to do this? That really takes a shift in thinking. How do we resource our schools, how do we provide training to our teachers, and how do we make sure that they have enough to do their jobs?”

Stocker said most veteran teachers have learned how to de-escalate and then show concern.

“It's making the right decision at the right moment, and that takes a lot of training,” he said.

Varnam agrees that it is difficult on top of everything that teachers and staff are already expected to do — veteran or not.

“It is hard work that [teachers] are trying to do, on top of following pacing guides and addressing every individual student need that isn't related to behavior. Behavior isn't the only thing that's supposed to be addressed in the classroom. So [they’re] trying to circle back and reteach these learning objectives and provide these supports and accommodations over here,” she said.

While this was a tough budget cycle for the district—facing a $20 million shortfall—and positions had to be cut this year, including social workers, counselors, and MTSS coordinators, Varnam said her division, student services, faced cuts along with all the district’s other divisions.

“All of our division leaders advocated to maintain the existing level of resources, but that does not math,” she said.

However, she said she wanted the teachers to know they are not alone in addressing problematic student behaviors.

“This has to be a team approach in the building. Do we have a magic team out there across the district that can swoop in and address this? No, and it also wouldn't work from a behavior standpoint. It has to be created within the learning environment. Relationships are the biggest tools,” she said. But added that her and her staff are there for administrators if they need additional support with continuing behavior problems.

Stocker said that moving forward, he hopes the schools get more funding to keep and expand important support positions and that veteran educators choose to stay in the profession.

“How do we as a society start to champion teachers," he said. "And start to consider them heroes?”

Range of Consequences - Policy 4300 by Ben Schachtman on Scribd