WHQR's Sunday Edition is a free weekly newsletter delivered every Sunday morning. You can sign up for Sunday Edition here.

This week, the New Hanover Community Endowment held a public meeting at Cape Fear Community College: a neatly curated 90-minute affair introducing new employees, announcing a new strategy, and hosting a brisk Q&A with the audience (the Wilmington Virtuosi Brass served nicely as the opening act, doing a snappy version of “Sweet Caroline,” which seemed very on-brand.)

The Endowment – as it has recently rebranded itself – has held these meetings twice a year since 2022, part of the legal requirements put in place by then-Attorney General Josh Stein when he approved the multibillion-dollar sale of the community-owned New Hanover Regional Medical to Novant and the transfer of nearly $1.3 billion in public money to what will eventually become a private non-profit foundation.

The meetings have come a long way since December 2022, when then-CEO and President William Buster stood on stage and read through $9 million worth of grant recipients, in alphabetical order. It was the epitome of ‘this meeting could have been an email,’ except that The Endowment was legally required to do something publicly. Over the years, there have been a few rocky performances, and some fiery criticism from attendees, but December’s meeting – the first with new CEO and President Dan Winslow at the helm – was relatively smooth.

At that meeting, Winslow rolled out two key ideas. The first was a high-level pitch for turning The Endowment into an R&D lab for philanthropic grants, sending out requests for research proposals, funding academic and think-tank work to generate potential solutions, and then turning that research into calls for grant applications. The second was the “grants rainbow,” which – while not particularly colorful – separated out the spectrum of the Endowment’s grantmaking into distinct bands: from modest $5,000 grants to help small non-profits and build capacity all the way up to big-swing, multi-year, multi-million-dollar grants. The meeting was decidedly big picture, short on details but long on grand ambition. Presented under the umbrella of what Winslow called “philanthropy plus,” it felt like an attempt to breathe some life into an organization that had seemingly lost its way, with staffing and strategy efforts going stagnant after the ouster of Buster in early 2024.

Flash forward to this week’s event, which was nearly seamless – well-organized, well-produced, and reasonably well-attended – and the tone was confident, upbeat, and celebratory, with members of the board, Community Advisory Council (CAC), and the executive team all thanking and congratulating each other on jobs well done. There was even a nicely produced video that showcased some of The Endowment’s work over the last few years, featuring harmonious teams of people building new homes, painting murals, delivering healthy food and healthcare services, and working with children (and also, for some reason, a rancher checking on his cattle).

There were a few pointed questions from the audience about the board’s diversity, funding for the arts, measuring grant impact, and support for the region’s elderly and migrant population (the latter currently being destabilized by dramatic shifts in refugee policy under the Trump administration). But there were also several audience members who mostly used their time to praise The Endowment, including New Hanover County Schools Superintendent Dr. Christopher Barnes – who is applying for a $4 million grant – who said he wanted to “set the record straight” that The Endowment had already “leaned in” on education funding.

“You can’t toot your horn, but I can for you,” Barnes said — although, honestly, I don’t think you can say The Endowment struggled on that front. In fact, much of the meeting was dedicated to celebrating the Endowment’s grantmaking to date, its new staff members, and its new strategic plan.

Board Chair Shannon Winslow (no relation to Dan) kicked off the evening by touting the $125 million The Endowment had committed to the community so far.

“We are very, very proud of those investments and the impact that they have had in our community,” she said, going on to praise the hard work of the board’s ad hoc strategy committee, Dan Winslow, and his team.

Winslow himself was introduced by emcee Carolyn Beatty, a CAC member, as the “ideal man” – a quote attributed to the Boston Globe. (There appears to have been a bit of a game of telephone on this: Beatty misspoke slightly, the Endowment has frequently circulated the title “Idea Man,” including on Winslow’s staff bio, though I can’t actually find that quote from the Globe. The closest I’ve tracked down is a reference to Winslow’s “reputation as both an ideas person and a showman,” from his 2013 Senate campaign – Winslow lost in the primary and walked away from political life.)

The praise continued as The Endowment introduced its three new vice presidents – whom Beatty referred to as “the triplets” — Emily Page, Tyler Newman, and Sophie Dagenais, who all have impressive CVs.

Dagenais, in particular, has a wide-ranging resume covering higher education, government, law, and philanthropy, including time as the director of the Annie E. Casey Foundation (an NPR funder). Dagenais took the stage to flesh out some of The Endowment’s grant process moving forward (more on that, in a bit) but also took time for some effusively kind words for the board.

“Our board, of course, is the ultimate steward, and we are very lucky to have them. I am not sure that I have ever, ever observed a more committed, hard-working board. It is absolutely extraordinary, I assure you,” she said.

There is, no doubt, a great deal of which The Endowment can be proud.

There’s a new name and a new website – which features a searchable database of grants (still a bit glitchy, but a good idea) and staff and board photos that flip from formal color profile images to smiling, casual, black-and-white shots when you hover your cursor over them (except Spence Broadhurst, whose subtle grin remains unchanged).

There’s a renewed sense that the CAC is engaged and involved (after last year’s formal protest that they were being ignored). There are new employees who seem raring to go in whatever direction the board and Winslow send them.

And, as we were reminded several times during the meeting, there’s been a lot of money put into the hands of people who are working hard to improve their community – 195 grants worth $125 million, with more in the pipeline and announcements planned throughout the summer and fall.

But, at the risk of crashing The Endowment’s well-earned party, I don’t think the people who showed up at CFCC on Wednesday (or the several dozen who watched online) were there for the self-congratulations. They were there to see and hear what The Endowment is doing – not just in terms of their latest grants, but where the foundation is heading after a months-long “strategic refresh.”

Expectations were high. As Winslow himself told me, it was set to be “transformational.”

Back in March, Winslow came to the WHQR studios to record a short PSA on The Endowment’s community and capacity grants. These grants, worth up to $5,000, could provide crucial assistance to small nonprofits but, in the grand scheme of things, they’re a fraction of the Endowment’s annual giving (less than 3%, even if the Endowment awarded the full $5,000 for every one of the 313 applications they received).

When we wrapped the interview I asked Winslow what he thought the next big “tent pole moment” would be for them, following Winslow’s debut at the December meeting.

Winslow pointed ahead to the May 21 public meeting, telling me, “we’re looking at some – what would be, I think, fairly considered transformational change.”

I told him I looked forward to The Endowment defining that term – “transformational” – in large part because his predecessor, William Buster, struggled to explain the concept in a way that resonated with the public. I said I didn’t fault Buster, because it’s a tough concept to get across.

Nonprofits have long operated with a scarcity mindset, scrambling annually for funding – to say nothing of the upheavals under the Trump administration – and are often limited to addressing the symptoms, not the root causes, of socioeconomic issues. There are great organizations that provide lunches for students, legal aid for tenants, child care for working parents – but none that truly lift families out of poverty in a way that would render those services unnecessary. That would be transformational, but it’s hard for people to imagine, because the status quo of poverty and economic disparity is so thoroughly baked into our reality, even for nonprofits who work to address those issues.

So, I was curious to hear what Winslow imagined as “transformational.”

“Watch and learn,” Winslow told me. “We have something cooking.”

On Wednesday, Winslow introduced what he’d been working on.

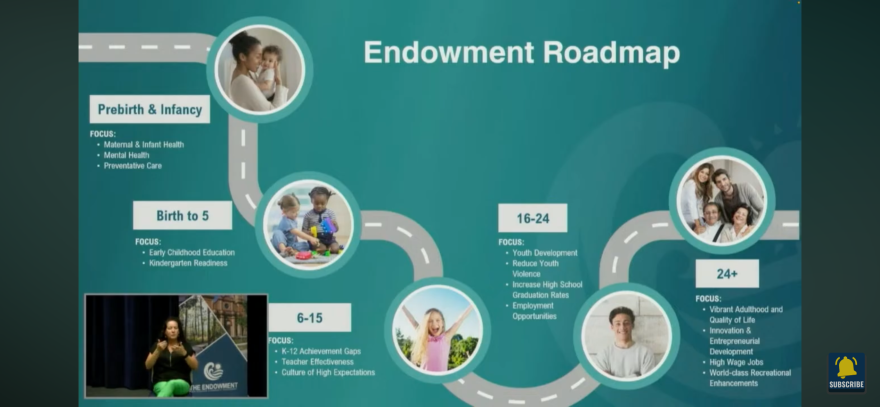

“Last year, at the public meeting, I introduced you to the concept of our grants rainbow, where we segmented our grants program into understandable concepts to make The Endowment accessible and relevant to more people in our county this year, I want to introduce you to The Endowment roadmap,” Winslow said, unveiling a board game style graphic of a road leading from birth to early adulthood.

Winslow laid out several waypoints, with different issues associated with each subsequent age bracket.

- For “pre-birth and infancy” – maternal and infant care, mental health, and preventative care

- Birth to age five – early childhood education and kindergarten readiness

- Ages six to fifteen – K-12 achievement gaps, teacher effectiveness, and a “culture of high expectations”

- Ages 16-24 – youth development, reducing violence (including gun violence), increasing high school graduation rates, and providing employment opportunities

- Ages 24 and up – providing “vibrant adulthood and qualify of life, developing innovation and entrepreneurial opportunities, creating high-wage jobs, and “world-class recreational enhancements”

This road map, Winslow said, was the result of The Endowment’s deeply intentional and multi-faceted strategic refresh process. He said it represented the “convergence” of the Endowment’s four pillars – education, social and health equity, community safety, and community development – and the foundation’s significant resources, which in financial terms look like $85 million in annual grants within the next few years.

Winslow noted that, in addition to the road map, The Endowment would continue to focus on housing and access to nutritious food, as well as “unique opportunities that arise that we didn’t foresee” and emergency response (for example, hurricane recovery).

“Our vision as we travel along the road is to live in the healthiest county in North Carolina with the number one ranked school system in the state, where every New Hanover County neighborhood is safe and resilient […] and we have a vibrant economy and a quality of life for all,” Winslow said.

But, as I sat in the audience texting with members of the nonprofit community, I heard some frustration. The road map Winslow presented was not new – there’s really not an issue there that hasn’t been discussed ad nauseam over the last five years – and he’d said nothing about how The Endowment would prioritize the issues, how it would convene organizations around particular projects, or what success would look like in terms of measurable goals.

Many I talked to felt Winslow had essentially laid out the vast majority of the issues facing New Hanover County and, other than arranging them on a ‘road map,’ had not advanced an explanation for how The Endowment would address them. I’d been hoping for “transformational,” but I had to agree with that assessment.

Later in the meeting Dagenais – the new VP of programs and grants – delved a little deeper into what The Endowment would do with its new strategy. But, though I have no doubts about her expertise, her explanation felt very general.

Dagenais was charming and funny when she went off-script. She got the best laugh of the evening when referring to Newman as “my triplet,” pausing for effect, and then adding “we’re fraternal” with solid comic timing. But her actual speech was a wall of jargon and buzzwords. She deployed phrases like, “zone of alignment,” “tactically, this also contemplates convenings,” and “change occurs at the speed of trust,” while eschewing details and examples.

“We want to be flexible, and we want to be disciplined. We'll prioritize impact, sustainability, and alignment, and we will intentionally target gaps and disparities. If we don't, we won't achieve those bold goals. Progress will demand that we confront disparities head-on with data, courage, and resolve,” she said. “We will use the rainbow as a framework to illustrate the range of grants and the partnership pathways that will help us bring that shared vision to life.”

Dagenais said The Endowment would be working with the community, that it would “learn from the agencies and the organizations that are out there doing the work,” that it would rely on data, explore successful models in our own and other communities, convene granters (like other foundations and governments). That’s all for the good, but none of it is new or enlightening. If I’d sent a reporter to cover the meeting, asking them to gather the basics — who, what, where, when, and why — I think they’d have come back largely empty-handed.

I take it that Winslow is the big picture guy and Dagenais is the detail-oriented operations person, but they both felt like they were describing the situation from 30,000 feet, if not low-Earth orbit.

Dagenais also noted, as Winslow and other Endowment officials have frequently reiterated, that The Endowment is relatively young.

“We are big, but in many ways, we are still a startup. I have a feeling that a lot of a lot of you in this room know what that's like,” she said. “You've been there with your own organizations. You remember the growing pains and the fits and starts and all the learning that comes with trying to build something meaningful.”

The Endowment is relatively young, and it still has a couple of years before the IRS regulations requiring it to put out 5% of its assets’ value in annual grant spending (that’s the $85 million figure that’s been batted around, although it could be higher depending on how its $1.6 billion in investments does on the market). Winslow has been on the job less than a year, Dagenais just a few months.

But I think some of the concerns I’ve heard this week are not just that the public is impatient (although they are), not just that Winslow promised something transformational. It’s that he really thinks the road map laid out this week is transformational, and folks are struggling to see how.

The morning after the meeting, I got a chance to ask him about that.

Sitting down at The Endowment’s offices in downtown Wilmington with Winslow, communications director Amber Rogerson, and marketing director Jodi-Tatiana Charles, I held the ‘road map’ in front of me. I asked Winslow, “What about this do you feel is transformational, compared to what, say, The Endowment was doing six months ago?”

Winslow launched into hypothetical examples, like attacking racial disparity in the infant mortality rate for Black babies and the third-grade reading levels of Black students. He talked about the crippling economic burden of childcare and the positive impact of neighborhood basketball programs on violent crime statistics. (He didn’t mention “world-class recreational enhancements.”)

Since maternal health is a major issue, which Winslow had brought up several times, I had to ask him about The Endowment’s narrow focus on New Hanover County, largely to the exclusion of other southeastern counties (whose residents helped NHMRC grow in value to the point where its sale made The Endowment possible).

“Are you going to go into New Hanover Regional Medical Center and pick winners and losers based on zip code? Meaning, based on county of origin? ‘Cause all of these moms are coming to New Hanover Regional Medical Center to have their children, but some of them are from Brunswick, Pender – are you gonna say, ‘Sorry, ma’am, but you live too far west by about two miles?’”

“I don’t know yet, we’ll have to see,” Winslow said, reiterating that The Endowment’s founding documents describe the defined beneficiaries are “New Hanover County and region,” adding that grants could have “collateral benefits” for people outside the county, as long as the primary focus was New Hanover.

Setting aside the county boundary issue – admittedly, one of my hobby horses – I got down to the main issue: I hadn’t heard anything truly new or transformative on Wednesday night.

“There’s nothing here I haven’t seen before,” I told him, holding up the road map. “There’s people in the community who have been saying all of these things for a long time.”

“Did any of them have $500 million to put behind that,” Winslow shot back.

I admitted that they didn’t, but pushed the issue.

“I’m just being candid with you,” I said. “I don’t see how we are any further down the road, no pun intended, than we were two years ago. We know what we need, we know we have money. I don't see anything else on the table that has changed the equation other than an adorable graphic. I'm just being blunt.”

“Ok,” Winslow said, not missing a beat. “Hold my beer.”

He said The Endowment is going to “work our strategic implementation plan over the next six to eight months, we’re going to have a series of convenings with people.”

Winslow suggested a possible childcare worker pipeline and plans to support more licensed childcare facilities.

“You know, a lot of entrepreneurs and innovators, they go into a big bold idea, but they don’t know if there’s a market. We know there’s a market. So now we just have to address the need,” he said.

Winslow said he was confident that the new road map – approved, he reminded me twice, by a unanimous board vote — would generate real change in the community.

“This is where we're putting our firepower, this vision, for at least the next five years, and possibly longer,” he told me.

“I’m telling you, what I hear is that this is not a vision. This is just a one-pager or summary of what exists,” I said.

“Stop talking to cynical people, Ben,” he said.

We moved on to some other topics, but as we wrapped up, we politely sparred a bit more over The Endowment’s transformational new plan. Winslow told me again, “This is going to be our laser focus for the next five plus years. And to the exclusion, potentially, of things that are not on this path.”

“I will say, if I were you, I would not say ‘laser-focused,’ because this is everything,” I told him. “You can't be laser – if you focus on everything, you're focused on nothing.”

“Well, I say, okay, a big fat laser, because it's—” Winslow started to say.

“That’s not how lasers work,” I interjected. “I’m begging you to give up the laser analogy.”

“All right,” Winslow said, laughing. “I concede the point, counselor — but here’s my point, Ben: there’s a lot of stuff that’s not in this path.”

I quote this exchange, in part, to show that Winslow is always game for a back-and-forth, not something I can say about everyone in his pay grade. He conceded the point about lasers, and I conceded his point that there were things that weren’t on the roadmap (it wasn’t everything, that’s true). But it was clear we were going to agree to disagree on the broader message he’d delivered this week.

And maybe Winslow is right and he’ll prove me – and other cynics – wrong. I am wholeheartedly rooting for that outcome. I will eat my fair share of crow, and more, if that comes to pass. (Roast crow, crow casserole, crowburgers, corvid noodle soup, you name it.)

But I do wonder what the community thinks of The Endowment, when they think about it at all. Is it just an ATM, a stopgap for local governments looking to tighten their budgets, a weirdly insular group of people dolling out grants based on private conversations had at closed meetings? Or do they see it as the big, bold, thought-leading, community-shaping organization Winslow presents it as?

The Endowment knows more than I do. I’ve had plenty of conversations, but they skew heavily toward people in the nonprofit world who are fairly plugged in. I’ve got anecdotes galore, but The Endowment has data.

Specifically, this spring The Endowment commissioned a survey from Emerson College, polling over a thousand people on how they feel about The Endowment, whether they trust them with $1.6 billion in essentially public money, and other questions.

In late April, I asked The Endowment if they could share the survey results. Rogerson told me they’d be announced during the May meeting.

But that didn’t happen.

I asked Winslow what happened and he said he’d “rethought” releasing them. I asked if that was because they were bad, but he said, “I loved it. I loved it. I loved the survey results.”

He didn’t give many specifics —although he confirmed a rumor I’d heard that more than a third of survey respondents said they didn’t know much of anything about The Endowment, which is “bonkers,” as I said to Winslow. He did say the results affirmed The Endowment’s new strategy.

Because we had limited time, I let the survey issue go. However, after our interview, I asked for some official clarity on the decision not to release the results.

Here was Winslow’s response:

As part of the strategic refresh process, we consulted with the Board, staff, CAC, local and regional experts and practitioners, and national subject matter experts. To understand whether our early thinking aligned with broader community views and values, I commissioned public opinion research by a nationally respected firm to seek community-wide input. That information was shared with the Board along with all the other supporting material. To avoid undue emphasis on any single source of information, we will keep these documents internal as part of our deliberative process. But I was pleased that there is strong alignment between the Roadmap and community priorities.

Now, this is the kind of stuff that drives journalists nuts. Commissioning a high-quality survey, celebrating the results, and then burying them doesn’t feel like it’s living up to The Endowment’s core value of transparency — a value Winslow has repeatedly invoked starting with his first public comments as CEO and president.

It’s also worth noting that if The Endowment had been established as a public entity, we would have just filed a Public Records Request. But that’s something the founders explicitly contemplated and sought to avoid, so here we are.

As I’ve written and said many times before, in the next decades, even if only by accident, The Endowment will do tremendous good in our community. If The Endowment settles into a predictable role bankrolling existing nonprofit programs and plugging holes in local government budgets, it will still help improve — even save — lives in New Hanover County (even cattle ranchers, I imagine).

But if The Endowment is going to change the world, at least for the nearly quarter million people in its chartered purview, it will have to do more — and it will have to bring people along with them. And that’s not me throwing a gauntlet down, that’s the goal The Endowment has repeatedly and publicly set for itself.

So, on that note, let me say two final things

First, The Endowment cannot fail, not really, not short of a total stock market collapse. It can make mistakes, head down blind alleys, even blow millions of dollars on unfruitful ideas. But it’s set up to run in perpetuity — think $100 million a year or more, forever. It’s hard to wrap your head around that sometimes.

By way of example, one question posed on Wednesday was whether The Endowment could fund a new Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, prompting cheers and laughter from the audience.

Winslow dismissed the idea, saying, “Well, we could do that. We could do that and then we’d be done.”

He didn’t elaborate, so I don’t know if he meant the Endowment could spend $1.1 billion (the latest estimate for a new bridge) from their principal or just be tied up in annual payments for the foreseeable future.

I know it was an off-the-cuff remark, but it did seem either a little disingenuous or ignorant about The Endowment’s actual financial firepower. They could buy a new bridge and still have a half-billion dollars. A better financial option would be a 20-year payment plan, which wouldn’t touch The Endowment’s principal; that’d still leave $25 million or more a year to spend. Would they have to tweak some bylaws? Probably. But the point is they could do it.

(Do I think that’s the best use of The Endowment money? No. And, obviously, I think Senator Thom Tillis and Congressman David Rouzer should get their butts in gear and make sure we don’t lose that quarter billion dollar federal grant, but that’s another story.)

But back to my point, The Endowment has time to figure things out. Past leaders have been cautious — to a fault, even — when it came to big swings. But they shouldn’t be.

Because of its strength and stability, The Endowment should be well-equipped to take criticism. With respect to Dagenais, they’re not a startup, they’re not some fledgling company forced to sink or swim on a brutally short timeline. Startups don’t have perpetuity to experiment or a billion-dollar cushion (excluding OpenAI, which I’m pretty sure is a scam).

For all the talk of transparency, The Endowment remains largely tucked away from public view. Dan Winslow does an admirable job of taking point, and Shannon Winslow (like Bill Cameron and Spence Broadhurst before her), has also amiably taken on the role of spokesperson from time to time. But the board’s other 12 members — effectively the jury when it comes to the fate of philanthropy in our town — remain mostly silent, safely ensconced in private meetings the public cannot attend and for which there is no public record.

Meanwhile, criticism — of the healthy, earnest, open variety — from community leaders has been somewhat scarce, especially from the nonprofit sector. It’s not that there are no concerns, they’re just not spoken aloud. My private conversations about The Endowment bear almost no resemblance to the public offerings of tribute, praise, and gratitude.

Listen, I work for a non-profit, so I understand the deferential posture that many have taken toward The Endowment during their meetings, and in general public conversations. I’m not shaming anyone for playing the game. And I’m not saying gratitude is the same as groveling.

But I think all this genuflecting has obscured the actual history and purpose of The Endowment.

What we’re really talking about is public money, taken out of the public sphere and placed in the care of a private foundation. The Endowment’s board members – noble, and caring, and hard-working as they are reputed to be – are giving the public back its own money. Now, the time and energy they spend — and it is considerable — are given altruistically. While Winslow and the triplets are handsomely compensated, the board works for free. And they deserve credit for that.

But they are not themselves billionaire philanthropists, the money is not theirs to give, and The Endowment’s grants are not a sign of their generosity. It is the people’s money and it is The Endowment’s legal duty to return it to the people, in the form of grants that address the most pressing issues in our community today. And it is, I think, fair for people to want a better, clearer idea of how they intend to do that.

For what it’s worth, I’ll disclose that WHQR has applied for grants, and received some funding, from The Endowment; that includes several applications for capacity grants, which are expected to be announced next week (I could have held this column until after that, I’m sure someone will say). I’ve had some friends and colleagues suggest that maybe I should go easy on The Endowment, or just find a different story entirely, especially with the Trump administration attacking public media funding on several fronts.

To all that I say, with love and all due respect:

Hold my beer.