A focus of controversy in recent weeks has been Policy 5120. The policy addresses the roles and responsibilities of the school administrators and staff as well as expectations of the conduct of School Resource Officers (SRO) — law enforcement officers who work on school campuses.

The main concern was new language that suggested students could be interrogated without a parent present — something critics take issue with.

Angie Kahney, a social worker and advocate with New Hanover County Schools United for Students said she sees an unwillingness from the board to hear and address parents’ concerns, “The actual board doesn't really seem to care very much. I mean everything that they do screams to families that they don't want their input.”

But parents believe Policy 5120 can have lifelong implications.

So parents like Amanda Krug, a mother of three kids in the New Hanover school system are speaking out: “I think it's disturbing that a teacher can surrender our child to a police officer, or that the administrator can surrender our child to a police officer to be questioned, interrogated, and searched.”

She also believes the current policy gives too much discretion to school officials.

“We’re going to have a 20 something-year-old with a Bachelor's Degree in education surrender my child and their rights to make a possibly life-changing legal statement to the police officers,” she said.

What are SROs? History and concerns

SROs have been in some schools since the 1950s but became far more prevalent after the 1999 Columbine School shooting. In New Hanover County, the program is run by the New Hanover County Sheriff's Office and staffed by deputies, along with some Wilmington Police Department officers (who answer to NHCSO for SRO-related issues).

The program, housed under the NHCSO's Detective Division, has been overseen by Lt Christopher Smith for 16 years. Smith recalled the impact of the 1999 school shooting.

“After that, there was a focus on putting more law enforcement officers in school settings for protection with the mission of stopping another Columbine from happening,” he said of the program.

But as the U.S. revisits police practices, activists have begun to demand that police be replaced by counselors. Many believe the presence of law enforcement in the school setting exacerbates mental health issues and escalates established community tensions between police officers and minority communities. Advocate groups also allege the SRO program creates a 'school to prison pipeline.'

Lt. Smith agreed that initial versions of the program did require reevaluation.

“The unintended consequence with more law enforcement officers working in schools is [that] you start to see behavior by students that traditionally was dealt with from a school discipline standpoint, beginning to be taken care of from a law enforcement standpoint. Yes, the behavior may be illegal, in terms of an assault or a fight, or disorderly conduct, but you start to see those things sort of fall into the criminal justice realm with the SRO as being there,” he said.

However, Smith believes that as law enforcement identified this issue around the mid-2000s, they changed their practices.

“In New Hanover County what we’ve done is say ‘let's work together to offer resources to our juveniles.’ So that we're not criminalizing behavior that's probably better handled with school discipline or handled in another manner,” he said.

Smith said the current diversion programs have been successful at keeping school issues from being unduly criminalized.

“We’ve seen it work. In the 2018-2019 school year, we saw approximately 76% of all school-based criminal offenses diverted to a community resource," he said.

Kahney said although she has seen the success rate and has high praise for the diversion programs, some schools still don’t use them.

“There are a lot of other strategies, proactively de-escalation strategies that can be used, as opposed to just resorting straight to questioning and interrogation, but the schools are still not using that. And I think that's largely because of these big contracts that they have with law enforcement,” she said.

She said the cases where the new policies fail dramatically are when an officer has a run-in with special needs and minority groups. The issue, she said, is the officers’ lack of training, understanding, and ability to know how to work with those kids who have been identified with cognitive and mental differences, as well as minority and LGBTQ students.

“Law enforcement doesn’t really abide by special needs plans, or not even trained in that, you know, so you have one group that's coming from that aspect. And then law enforcement is more of a fear-based kind of punitive approach and so they conflict a little bit,” she said.

The Policy & The MOU

So what does Policy 5120 actually say — and why are parents so concerned?

Policy 5120 was put up for first reading during the school board's July regular meeting — with the added language: "When law enforcement officials find it necessary to question students on campus or take them into custody, the principal shall make an effort to notify the parents or guardian of the student, unless requested not to do so by the law enforcement official. If the student is taken into custody of the law enforcement officials, the superintendent's office must be notified."

Facing pushback around wording about allowing criminal interrogation of children without parent’s notification and presence during criminal interrogations, the board struck the proposed new language and changed the policy to reference the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

But the MOU had similar language: "In cases where the parent(s) or guardian cannot be reached and any questioning of a student is conducted without parental notification, the school principal or designee must be present unless the SRO directs otherwise for safety or investigative reasons."

The MOU allows both for the school to act in loco parentis during interrogations, which the courts have disagreed with. It also appears to allow questioning without even a school representative present, at the discretion of the SRO, which appears to fly in the face of state law and U.S. Supreme Court precedent.

It's worth noting that Policy 5120, like all policies, is part of the district's public-facing website; the district often refers parents to these online policies when they have questions or concerns about how the school operates. The MOU, meanwhile, is the contract between the district and the Sheriff's Office — and while it is a public document it's a bit harder to find online, and it's written in legal jargon, making it harder to parse for the layperson.

It's also worth noting the MOU is relatively new. In prior years, the district used an interlocal agreement with the county, municipalities, and law enforcement. At the beginning of the 2020-2021 academic year, an MOU was approved for the first time — without apparent issue — by both the school and law enforcement. The MOU initially put forward by the board this summer uses identical language as last year's contract.

In the July 13th Special Meeting, community member Barbara Anderson expressed her concerns after this change: “Even though the language was changed prior to the last board meeting regarding parental notification, this policy is still unclear as to what happens and to which age groups it addresses. Does this mean the student was arrested? Are they restrained with handcuffs? Even elementary students? Are students provided Miranda rights? Do they even understand the rights when they're in elementary? Is a parent present when a student is arrested?”

Just moments later, board member Nelson Beaulieu said “The MOU dictating the relationship between SROs and our county schools, and the New Hanover County Sheriff's Office MOU was passed unanimously in June. And it addresses all of these issues very, very clearly.”

Beaulieu’s 'clear as day' statement only fueled suspicion and concern according to Kahney, who reported receiving an influx of calls, messages, and emails from parents about the policy and MOU.

So the board, or at least some of its members, responded by inviting Judge J.H. Corpening, chief district judge for New Hanover and Pender, to speak at the August 3rd meeting. Corpening has years of experience with juvenile court, and played down concerns about the policy.

Board members Stephanie Adams, Stephanie Kraybill, Pete Wildeboer, and Nelson Beaulieu pushed to pass the policy “as is,” and Wildeboer stated that the concerns were addressed by Judge Corpening, again saying the policy was very clear. But board members Judy Justice and Stephanie Walker both expressed their surprise at Corpening’s visit.

Walker said during that meeting, that if she had known Corpening was going to attend she would have come prepared with the questions she had received from community members and asked for the policy to go back to the committee for review.

“Maybe he [Corpening] alleviated their concerns or maybe he expanded them some,” said Judy Justice. “This has been a very useful experience having him here talking about this particular policy. But I mean what is the harm in waiting a week or two weeks when we have our interim meeting to doing this? Like we said we were going to do originally.”

Parents and legal officials agree parents must be present during criminal interrogations.

Angaza Laughinghouse, attorney, and advocate at the ACLU of Raleigh specializes in legislation and legal matters of School Resources Officers spoke about the policy and the law.

“This policy clearly contradicts what the law says. The Constitution, the Fourth Amendment, and even North Carolina State law clearly say that if cops are interrogating anybody, number one, they have to read the Miranda Warning. If the person is a juvenile and 18 years old, they have to notify them of the rights to have their parents present. And on top of that, if they are under 16 years old, they cannot be questioned in custody, without having a parent or an attorney, or guardian president. So this school policy just completely ignores that fact ignores the law,” he said.

Lt. Smith, the deputy in charge of all New Hanover County SROs, said North Carolina law clearly addresses this.

“So custodial interrogation, when it comes to the juvenile, the standard is essentially the same as an adult meaning that, you know, the juvenile, or the adult, they're in custody, meaning that they're, they're not free to leave. And that's whether they're restrained or not, and that they are going to be questioned by a law enforcement officer about a crime that they're suspected of committing… a juvenile has to be read a specific Miranda warning and that's set forth in North Carolina §7B 2101. That, you know, the juvenile be advised of their rights and their right to have a parent guardian or custodian present.”

What does the statute say?

State law clearly lays out the rights of juveniles — including the right to remain silent, the right to stop questioning, and the right to have a parent, guardian, or custodian present. And, while the school's language appears to suggest that the 'custodian' role can be filled by a principal or other administrator, many legal experts disagree.

During the August 10 policy committee meeting, Assistant Superintendent Julie Varnam stated that the Sheriff’s Office had problems with the language and was editing the document to reflect the law; a spokesperson for NHCSO confirmed this. While it's not yet clear what specific changes the Sheriff's Office will request, it does seem to support concerns from parents that the MOU — 'as is' — had legal issues.

The burden falls on children

Kahney said this policy has historically put the burden on the kids to speak out, “Our kids have to be very empowered to pretty much demand that their parents be there or another advocate. And especially when you're talking about kids who are five years old, they're not going to do that, like they're a bit intimidated by an officer with a badge and a gun… children are taught to respect this authority.”

That sentiment can be heard in the 2001 Supreme court case J.D.B. v North Carolina. The court ruled that “it is beyond dispute that children will often feel bound to submit to police questioning when an adult in the same circumstances would feel free to leave… we hold that a child’s age properly informs the Miranda custody analysis.”

Justice Sonya Sotomayor expressed this concern during the hearing, saying "I'm hard-pressed to think that anyone would believe that if you took a 9-year-old out of his classroom and the assistant principal walked him into a room and said 'these guys wants to talk to you,' that the 9-year-old would think he's free to leave."

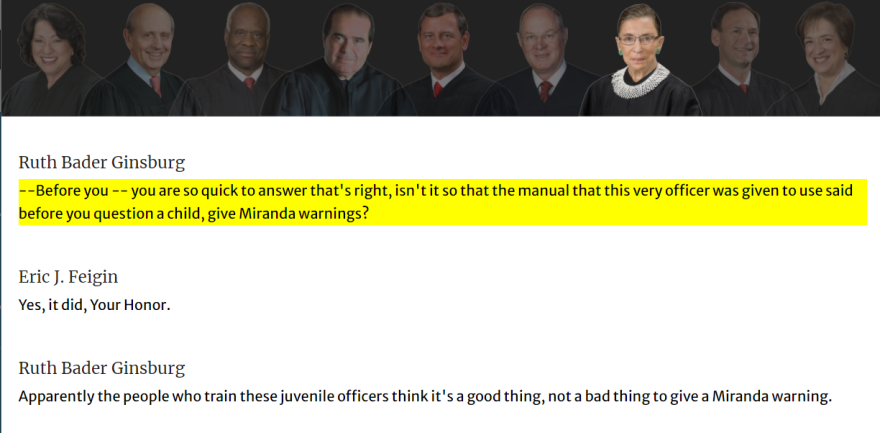

The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted that the North Carolina SRO training manual itself required the reading of Miranda in this case, saying "the people who train these juvenile officers think it's a good thing, not a bad thing to give a Miranda warning."

This burden leaves one asking what one lawyer asked the Supreme Court court to consider, in the 1967 case In re Gault:

“Furthermore, experience has shown that "admissions and confessions by juveniles require special caution" as to their reliability and voluntariness, and ‘[i]t would indeed be surprising if the privilege against self-incrimination were available to hardened criminals, but not to children.’”

As things stand right now, the board is looking to reconsider the MOU — and the Sheriff’s Office may ask for additional changes as well. This stands in stark contrast to the unanimous approval of an identical MOU last August — and to the attempt to pass it the MOU 'as is' earlier this summer.