Note: This article has been updated with additional information from the Wilmington Police Department concerning the use of force data.

For over a decade, the Wilmington Police Department has publicly posted annual reports detailing complaints against officers, internal investigations, use of force metrics, and other data. This year, the department stripped the report down to the minimum requirements. Using open records laws, WHQR reassembled the report --- the results initially showed a significant increase in use of force incidents, but WPD said there was a 'mix-up' that inflated the number.

---

Since 2008, the Wilmington Police Department has annually released a report from its Internal Affairs division (after 2016 known as the Professional Standards division). Traditionally, these reports are released in the spring or early summer, and have been two to four dozen pages, containing a number of data sets and infographics.

The 2019 report was quietly released in mid-October. It was just four pages long and wasn't posted along with the past decade of other reports (it was posted as a news item on the department's website, here). The report was largely good news for the department, showing a decrease in citizen complaints and allegations, and an decrease in sustained investigations (after a spike in 2018).

Those four pages contained the minimum requirements of Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, Inc. (CALEA), an independent organization that maintains standards for public safety and law enforcement agencies. The CALEA requirements cover the complaint process: how many complaints were filed, how many were investigated, how many determined a policy violation, and what kinds of disciplinary action was taken. This is the same data published by other CALEA-accredited agencies in the area, including the Sheriff's Offices of Brunswick and New Hanover counties, and the Wrightsville Beach Police Department.

It's worth noting that CALEA accreditation is often seen as a 'best-practice,' but it's far from mandatory. Less than a quarter of state and local law enforcement agencies are accredited nationwide, according to CALEA. Of the more than 500 law enforcement agencies in North Carolina, 74 are accredited and 21 are in the accreditation process (you can find an online accreditation database here).

What the report left out --- and what, in past years, has made it so notable for its transparency --- is a wide range of important data sets: use of force data, call load, officer demographics, police pursuit data, biased-based profiling data, and personnel early warning stats (drawn from the department's system for identifying potential problems ahead of time).

So, what happened?

According to Interim Public Affairs Office Jessica Williams, "Due to how tumultuous this year has been for the police department — with changes in leadership, the pandemic, and the loss of PIO Linda Thompson— Chief [Donny] Williams made the decision to only release the information we are required to release by our accrediting agency, CALEA, for the time being."

Former WPD Chief Ralph Evangelous retired at the beginning of 2020; Williams was named Interim and later appointed the new Chief. Long-time Public Information Officer Linda Thompson, who worked in public relations for the department for a quarter-century, left over the summer to become New Hanover County's first Chief Diversity and Equity Officer.

Williams said she couldn't speak to how many employee hours it takes for Professional Standards to compile the data, but formatting for the most recent report took roughly 20-30 minutes per page for a 42-page presentation (or, roughly half a work week). Williams noted that the Public Affairs Division staff has been halved --- from four to two employees --- and so other efforts have also been impacted, including Williams' podcast 'Cops on Mic,' which is on hold. Some filming for 'Behind the Badge,' Chief Donny Williams' YouTube series, has also been interrupted.

The situation is temporary, Williams said, noting that "in 2021, we will combine the 2020 Internal Affairs report and the 2020 Annual Report into one — including use-of-force statistics for both 2020 and 2019. This is how we will release the information each year moving forward."

Williams also suggested that anyone interested in seeing the data --- like use of force stats --- that didn't make it into this year's report file a Public Records Request with the city.

In early December, WHQR filed a request under Under the North Carolina Public Records Law, G.S. §132-1, sometimes known as the state's sunshine law. The law requires government bodies to provide documents and, in same cases, data in a "reasonable" timeframe, although the interpretation of 'reasonable' has, historically, varied considerably. In this case, the City of Wilmington completed the request in seven business days. (The responses, which you can find at the end of this article, were produced as infographics instead of just raw data, which the city is not required to do.)

Public records show increase in use of force, WPD says data resulted from 'mix-up'

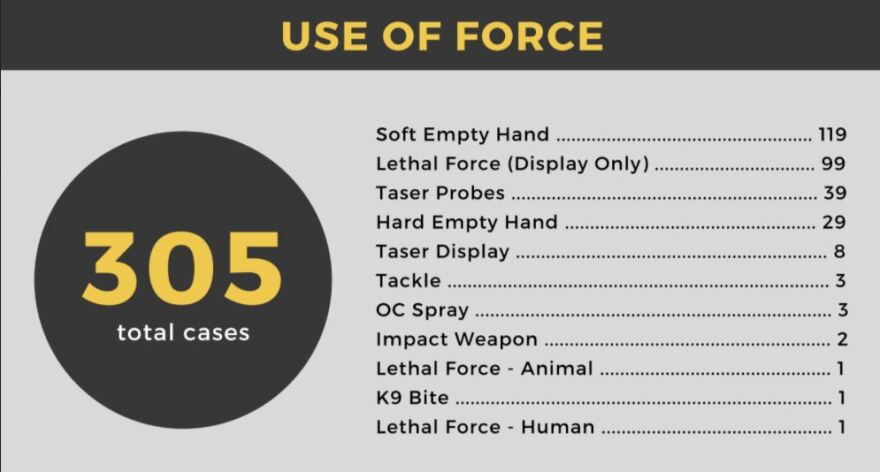

The results of the public record request showed a significant increase in the use of force. In 2019, the city reported there were 305 use of force cases --- an increase from the 185 in 2018 and nearly double the 153 in 2017.

For context, the increase from 2017 to 2018 had already caused concern with some officers, according to a Spring 2019 article in Port City Daily. According to city emails cited in that report, a WPD captain suggested that Hurricane Florence and an uptick in the abuse of crack cocaine and phencyclidine (PCP) may have driven the increase.

Update: Williams said, "there was a mix-up. This is part of the reason we wanted to simplify the IA report: these charts are too complicated." Williams said there were 183 use-of-force cases, and that the 305 number referred to the total number of individual types of force used: for example, is a soft open hand contact and a taser were used in a single incident.

According to the data provided by the city, the officers involved in use of force incidents mapped proportionately onto the department’s overall demographics --- meaning there wasn’t statistical evidence that officers of certain races or genders used more force than others.

Other data sets showed relative consistency from prior years in areas like vehicular pursuits (and crashes), bias-based complaints, calls for service, and other metrics. The information also showed a decrease in the number of personnel 'early warning' notices sent out (58 in 2019, down from 89 the prior year); these are messages sent to supervisors based on range of possible warning signs, like missing property, complaints, pursuit crashes, and other metrics. There were also two employee grievances based on the promotion process (personnel law makes the details of those incidents private).

--

You can reach Ben Schachtman at BSchachtman@whqr.org and find him on Twitter @Ben_Schachtman

2019 Professional Standards Report Wilmington Police Department by Ben Schachtman on Scribd

Employee Grievances and Misc. for WPD 2019 by Ben Schachtman on Scribd

Employee Grievances and Misc. for WPD 2019 by Ben Schachtman on Scribd