While the pandemic continues to stress the American healthcare system, nursing programs are turning away qualified applicants at record numbers. Why? There’s not enough faculty to teach them--because the job doesn’t pay well enough.

More Nurses Are Needed

There are over 2200 nurses at New Hanover Regional Medical system, and about 1700 of them work in hospital settings, according to Chief Nurse Executive Mary Ellen Bonczek. “So we hire a minimum of 150 new graduates every year. Last year we hired probably closer to 200,” says Bonczek.

Those new nurses come straight from local programs, at schools like Cape Fear Community College or the University of North Carolina Wilmington. The majority of graduates from those programs have jobs already waiting for them upon graduation and passing exams.

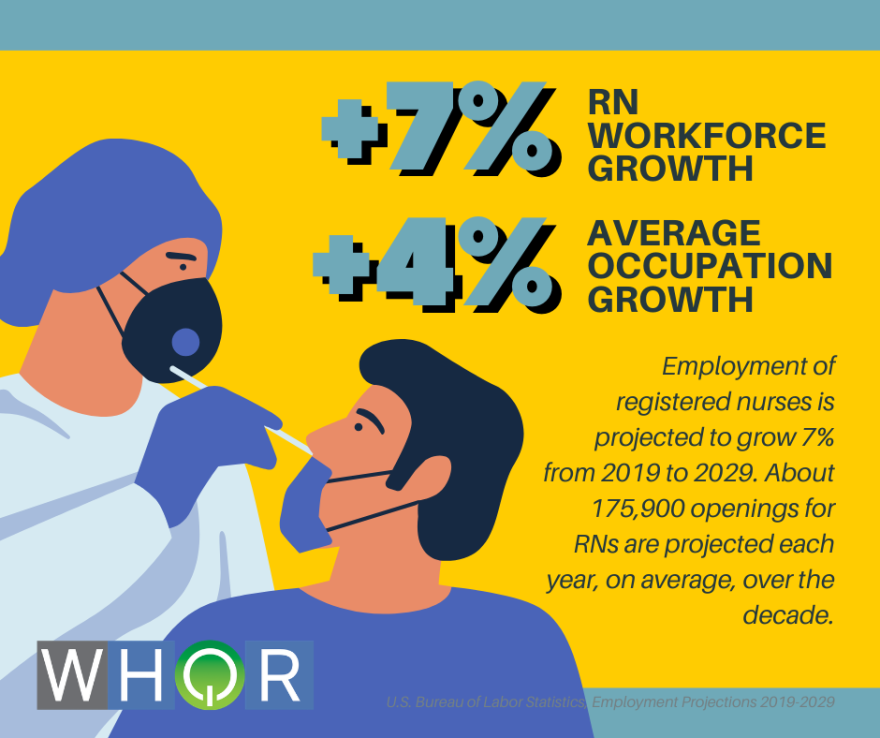

There are nearly 4 million nurses in the US alone--the largest majority of the healthcare profession, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Between Baby Boomer nurses retiring and that aging generation requiring more healthcare services, the demand for registered nurses is at an all time high. So why aren’t programs graduating more nurses?

It’s not for lack of applicants.

Application Rates Are Wildly High

“We here at UNCW, we always have high demand and that demand did not change.” Linda Haddad, Nursing Program Director at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, says their programs always receive hundreds of applicants--and that numbers haven’t noticeably changed since the pandemic began.

That consistently high application rate is true for the nursing program at Cape Fear Community College, too.

“We always have well over 400 applicants.” And that’s for just 80 spots, according to Brenda Holland, Department Chair of Nursing at CFCC.

According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, U.S. nursing schools turned away 80,407 qualified applicants from nursing programs in 2019.

The main reason nursing programs can’t accept these applicants?

There’s no one to teach them.

Not Enough Pay Means Not Enough Faculty

It’s not that people don’t want to teach, says Bonczek. It’s the pay cut. “There are some of my nurses at the hospital, across the health system that would love to teach, but they're not going to take that kind of a cut in pay.”

Simply put: a nurse makes more money in practice than teaching.

“When I first started, I took a pay cut,” says Holland. According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, nursing educators in academic positions earn significantly less--about $20,000, on average--than clinical or private-sector nurses with the same education. And it’s hard to find someone who can afford to take that major pay cut for their professional passion.

Holland: “We just had two faculty this past fall, we were looking for a faculty member and we had two turn it down before we found someone who would accept. And so we do get lucky in that, you know, sometimes we have nurses whose husbands make enough money that they can take a pay cut. And the schedule's nice. But it's probably going to cut, you know, $30,000 a year off their salary.”

The CFCC Nursing Department Chair says a nurse making $80,000 in practice might make $50,000 teaching at their program. Full-time faculty need a master's degree for teaching accreditation, whereas only an associate’s degree is required to practice nursing.

For nurses who do want to pursue education beyond an associate’s degree, the higher compensation in clinical and private-sector settings is enough to lure current and potential nurse educators away from teaching.

But who can blame them, when the pay differences are so stark? According to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, the average salary of a nurse practitioner, across settings and specialties, is $110,000. By contrast, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing reported in 2020 that the average salary for a master's-prepared Assistant Professor in schools of nursing was just $79,444.

As a result of these pay disparities, nursing faculty positions are difficult to fill, and some even remain unfilled. Data from 2019 reveals a national nurse faculty vacancy rate of 7.2%.

Enough Clinical Sites Are Available, Simulation Learning Helps, but Faculty Still Needed

Nursing education requires hands-on learning, with students training directly under current nurses in clinical experiences. This kind of training requires smaller class sizes--and hence, more faculty--to ensure close supervision in real-world healthcare settings.

Holland: “We have classes of 30, and we can't have one faculty take 30 students out to take care of patients--that wouldn't be safe, of course. So we need our clinical groups to be smaller.”

This small group learning can be complex to set-up, requiring cooperation between nursing programs and healthcare providers.

But finding appropriate clinical sites is more an exercise in creative problem solving than a barrier to accepting more students. In the Cape Fear region, outpatient practices and night shift rotations offer more potential clinical sites for nursing students.

Brenda Holland stresses that more clinical sites can’t be supported without more educators. “If we could find the faculty and have the resources to support extra students, then we would venture out and look harder for the clinical sites. But right now finding the clinical sites wouldn't do us any good.”

North Carolina does allow up to 50% of clinical nursing experience to be done in simulation labs, which reduces the strain of finding and staffing more clinical sites. Both UNCW and CFCC use simulation labs with their nursing students.

“Without those simulation labs, you know, your first hour and your 60th hour is in the hospital or in the acute care setting,” says Bonczek. “But in sim, you can actually hone a skill down on those amazing mannequins that are lifelike people. They even tell you when you hurt them or tell you when you gave them the wrong medicine. I've been through some of the simulations and they are phenomenal.”

While simulation labs and creative problem solving have helped nursing students gain clinical experience, the nursing faculty shortage remains the limiting factor when it comes to accepting more qualified applicants.

And this nursing faculty shortage is projected to worsen as faculty age continues to climb. The average age of a nursing professor with a master’s degree? 57. A doctorally-prepared professor? 62. As the current nursing faculty ages, a wave of faculty retirements is expected across the U.S. over the next decade.

And there just won’t be enough faculty to replace them.