A legal fight coming to an obscure board in Raleigh may change how short-term rentals — properties leased a few days at a time through platforms like Airbnb and VRBO — are taxed across North Carolina.

The results could have big implications for local government revenues and housing markets, especially in parts of the state popular with tourists.

How property taxes are determined

The board of county commissioners in every North Carolina county adopts a “schedule of values,” or a document detailing how government appraisers must calculate the worth of different land and building types.

State law requires the schedule to capture each property’s true value, as dependent on factors like location, condition, and use.

County and city tax officials then multiply a property’s value by the local tax rate to set its property tax bill.

For example, a home valued at $300,000 in New Hanover County, where the rate is 30.6 cents per $100 of assessed value, would receive a $918 property tax bill.

What about short-term rentals?

Schedules of values in North Carolina’s 100 counties don’t recognize short-term rentals as a separate property use. Instead, those rentals are lumped together with purely residential properties.

While short-term rental owners must pay other taxes on rental income, when it comes to property tax, local governments treat a house that’s constantly rented out to visitors the same as a house next door occupied by a family when it comes to assessing tax value.

Joe Minicozzi, principal of the Asheville-based municipal consultancy Urban3, challenged Buncombe County government over the 263-page guidelines it uses to assign property values to short-term rentals and other properties.

Vacation rental homes are often worth considerably more to their owners than are residential homes of similar size and quality. But because Buncombe’s schedule doesn’t include short-term rentals, the county isn’t legally allowed to take cashflow into account when assessing their property value.

As an example, Minicozzi pointed to 26 Upstream Way, a four-bedroom, whole-home short-term rental owned by Charlotte-based investors. Known as “The Luxury Asheville Affair,” the property was explicitly marketed on social media as a getaway for bachelorette parties. Buncombe property records showed the house was bought for nearly $1.2 million in 2024, yet the county appraises it at roughly half that value.

Note: NC Local reached out to Siva Naga Sindhur Kakani, owner of Asheville Affair LLC, for comment on the taxation issue. He did not respond, and the home’s website was subsequently taken offline. It remains available through the Internet Archive.

Minicozzi estimated that Buncombe County will lose about $15 million dollars in unrealized property tax revenue this year from short-term rental properties. That works out to nearly 3.5% of Buncombe’s current general fund budget and close to the $15.2 million the county raised through its most recent property tax increase.

“Airbnbs, VRBOs — they just don’t exist in our tax system,” Minicozzi explains. “We are not assessing those commercial investment properties for their income, and we should be. That would bring a significant amount of money to our community.”

Who decides how properties are evaluated?

The Property Tax Commission is the state body responsible for hearing objections to county schedules of values.

Minicozzi is asking the commission to confirm that short-term rentals are a commercial use and require Buncombe County to consider their income for valuation purposes.

The county, in its case brief, said short-term rentals don’t produce more income than regular rental properties, so there is no need to tax them commercially. The brief includes several case studies, based on average daily rates and occupancy over the last year, showing relatively limited returns on investment.

“The data indicates that the income generated by short-term rentals is not substantially higher than that from long-term residential leasing, reinforcing the notion that the highest value is derived from using the properties as permanent residences,” the county’s brief stated.

That conclusion may hold for the modest homes Buncombe featured in its brief, but Minicozzi contended that it’s inaccurate for properties like 26 Upstream Way. He estimates that some of the county’s highest-performing short-term rentals generate annual returns of up to 31%, compared with the average local hotel’s return of about 8%-9%.

Eric Cregger, Buncombe County’s tax assessor, declined to be interviewed for this story.

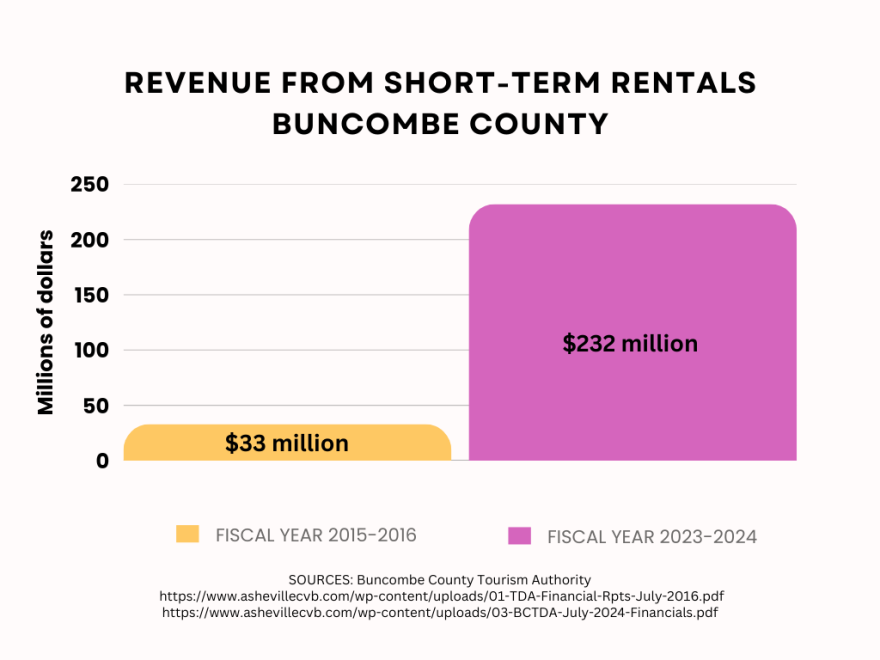

Buncombe’s contention that short-term rentals aren’t financially attractive, Minicozzi added, is difficult to square with the explosive local growth of those rentals in recent years.

Minicozzi said he isn’t advocating for all short-term rentals to be treated as commercial property, but he believes some should and their income should be accounted for in the assessment.

“The house that is pulling $300,000 per year in income is not the same animal as the house that is renting out a basement conversion in West Asheville,” Minicozzi said.

How does the appeals process work?

All North Carolina property owners have the right to appeal and ask for the value of their property to be reconsidered. By disputing a county’s assessment of their property, owners often end up lowering their property tax bills. One 2021 study from Durham County found that 80% of appeals were successful, while 60% of Wake County appeals succeeded in 2020.

A property owner must start the appeal process by contacting their county tax office sometime between January and April. Owners can submit supporting documents such as photos showing the condition of the property, sales records for comparable properties, and recent professional appraisals. A county assessor then reviews the evidence and issues an informal decision.

If the property owner disagrees with the assessor, their next step is the county’s Board of Equalization and Review. These boards, either consisting of or appointed by the county’s board of commissioners, must begin conducting formal hearings on tax appeals no later than the first Monday in May each year.

If a property owner still disagrees with the county-level ruling, they can go to the state Property Tax Commission. The commission’s quasi-judicial hearings are held over four days each month at the N.C. Department of Revenue’s headquarters in Raleigh.

Despite the important role of the Property Tax Commission, it can be difficult for the average resident to follow its operations. The body has not livestreamed its meetings since the end of pandemic-era virtual meetings in February 2022. It relies on an independent court reporter to record and transcribe proceedings, and members of the public must pay to access those transcripts.

Property Tax Commission judgements regarding a property’s value are final. However, if a taxpayer disagrees with the commission’s interpretation of the law, they can appeal to the N.C. Court of Appeals, and from there to the state Supreme Court.

What’s next?

Minicozzi’s case is unusual because it goes beyond a regular appeal to challenge the entire schedule of values, not just a single property value.

Under state law, his appeal must go directly to the Property Tax Commission.

If the Property Tax Commission upholds Minicozzi’s complaint, he believes other North Carolina counties will be empowered to consider short-term rental income as well.

His Urban3 colleague Andrew Fletcher said the approach would be particularly meaningful in Swain, Dare, and Avery counties, each of which has more than 100 active Airbnb listings per 1,000 housing units.

The hearing

The commission is set to hear the case at 1:30 p.m. on Monday, Feb. 9.

While the presentation of evidence and argument is considered public, the actual deliberations of the commission are closed. Stephen Pelfrey, the commission’s secretary, cited a state law that allows state agencies to close hearings held “solely for the purpose of making a decision in an adjudicatory action or proceeding.”

The Property Tax Commission generally issues its decisions on the day of a hearing and provides written documentation within 90 days. Those findings are public records that people can request through the N.C. Department of Revenue.

Commission hearings have no public comment period, and commissioners can’t consider comments submitted in advance by anyone who isn’t a formal witness for a party in the case. Members of the public who attend hearings are only permitted to record them, Pelfrey said, if they have “demonstrated sufficiently in advance that [their] equipment and recording activities will not interfere with the proceeding.”

This article first appeared on NCLocal and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.