The 287(g) program allows local law enforcement agencies to voluntarily enforce immigration laws under the delegation and oversight of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Agencies participate in the program by completing a letter of interest and filling out a memorandum of agreement for the enforcement model they choose.

After the passage of 287(g) in the mid-1990s, law enforcement agencies were slow to participate — the first police department didn’t join the program until 2002, according to a report published in the Du Bois Review, a peer-reviewed social sciences journal based at Harvard.

In December 2024, the American Immigration Council (AIC), a non-partisan organization that advocates for “fair and just” immigration policies, reported that 135 law enforcement agencies across 27 states had agreements with ICE. But that's apparently increased dramatically: as of July 11, ICE reported that the total number of agencies collaborating with them sits at 805, covering 40 states.

According to (AIC), the 287(g) program has faced criticism for being costly to municipal agencies, for historically targeting people with little or no criminal history, and for tarnishing the relationship between police and the communities they serve.

While immigration advocates’ criticism of ICE and the 287(g) program persists from past administrations, its implementation under Trump's current term in the White House prompts new questions.

287(g) Models

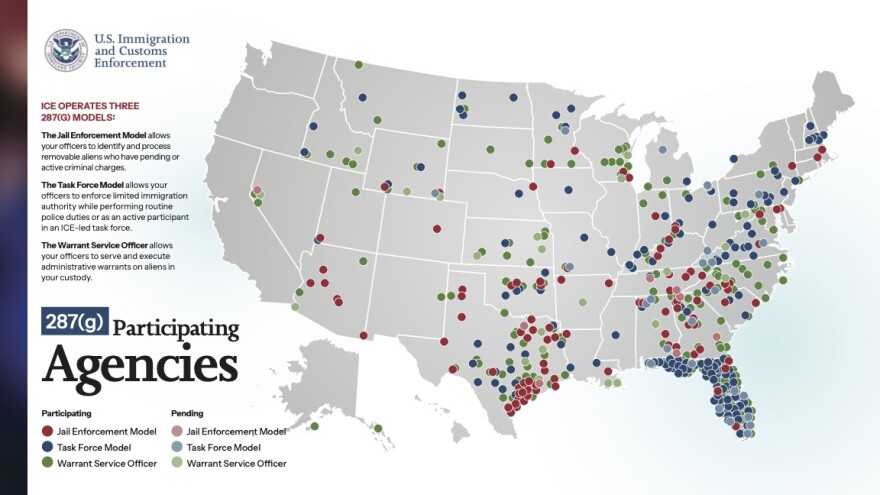

There are three models under 287(g) that designate certain local law enforcement agencies as additional immigration enforcement. This includes one model that was suspended in 2012 and brought back under Trump’s second administration.

The reinstated model deputizes local and state officers to enforce immigration laws during their routine policing duties — an authority normally reserved for federal immigration agents, not local police.

Below are the models as defined by ICE:

- The Jail Enforcement Model (JEM) is designed to identify and process removable aliens — with criminal or pending criminal charges — who are arrested by state or local law enforcement agencies.

- The Task Force Model (TFM) serves as a force multiplier for law enforcement agencies to enforce limited immigration authority with ICE oversight during their routine police duties.

- The Warrant Service Officer (WSO) program allows ICE to train, certify and authorize state and local law enforcement officers to serve and execute administrative warrants on aliens in their agency’s jail.

The Obama Administration discontinued the task force model and the Hybrid model in 2012, the latter allowed deputized officers to perform immigration enforcement functions within detention centers and in the field.

These agreement models were suspended after the Department of Justice conducted an investigation of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, and found evidence that these practices led to racial profiling and unlawful retaliatory practices against Latinos in that county.

The DOJ investigated a similar case of malpractice in North Carolina, in which Alamance County Sheriff Terry Johnson was on trial for racially profiling Latino residents and detaining people without probable cause.

As of yet, the new Trump administration has not revived the Hybrid model, but it has brought back the Task-Force Model.

Currently, there are 111 JEM agreements in effect in 27 states, WSO agreements with 266 law enforcement agencies in 34 states, and 360 TFM agreements in 30 states.

The shifting scope of ICE operations

Kathleen Bush-Joseph with the Migration Policy Institute said each elected administration has prioritized immigration enforcement in various ways.

For example, the Biden administration nearly matched the record 1.5 million deportations carried out during Donald Trump’s first presidency, she said, adding that what the current Trump administration is doing is very different.

“Biden deported people by quickly returning them at the US-Mexico border. So obviously, what Trump 2.0 is trying to do is way different,” Bush-Joseph said. “Now we're seeing the Trump administration actually try to use very similar tactics, but in the interior.”

As opposed to quickly returning someone who recently entered the states, according to Bush-Joseph, “now, they're quickly deporting people who've been in the country, many of them for more than a decade.”

Since 1953, the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) has had the authority to search and interrogate any person suspected of being undocumented without a warrant. Under federal regulations, CBP is allowed to patrol all regions within 100 air miles of any external boundary of the U.S. — this is known as the 100-mile Rule.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, two-thirds of the country’s population lives within this 100-mile zone. And some of the largest cities like New York and Los Angeles fall in this region; some states like Florida lie completely within the 100-mile boundary.

However, shifting from the U.S.- Mexico border to a much wider geographic area, including cities across the country, means an increased need for resources.

Because of this, critics of the program fear ICE may seek to carry out the current administration’s immigration overhaul on the backs of local law enforcement agencies — much more so than past iterations.

And in North Carolina, a growing number of sheriffs’ offices are complying.

A look at 287(g) agreements in our state

As of April, North Carolina had the third highest number of law enforcement agencies (LEAs) participating in the 287(g) program, with a total of 19 Memorandums Of Agreement.

Florida had the highest number of LEAs participating in the program, with a total of 243 MOAs with sheriff’s offices across their state. And Texas had a total of 77 MOAs.

Fourteen of North Carolina’s MOAs date back to 2020, one MOA was entered into in 2019, and four started this year.

Syracuse University Professor and expert on America’s immigration enforcement system, Austin Kocher, said the number of agencies contracting with ICE within a state doesn’t directly correlate with the amount of reported immigration-related arrests.

According to ICE’s 287(g) Monthly Encounter Reports for 2025, Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina have had consistent ICE arrests since the start of the year.

However, the reports from March and April would indicate that the number of ICE encounters is slowly but surely ramping up in states that have fewer ICE contracts.

“You're seeing that in Nashville right now, with the State Highway Patrol, working with ICE, doing all these traffic stops and arrests,” Kocher said. “There's no 287(g) there, and they're doing as much, if not more than, what we've seen in recent activity in Florida, which is saturated. So it doesn't always correlate super strongly, but there are very real effects.”

Some counties in North Carolina have had consistent immigration-related arrests since January.

The Cabarrus County Sheriff’s Office has made four arrests, Gaston County Sheriff’s Office has made two arrests, and Henderson County Sheriff’s Office has also made two arrests.

Whitfield County Sheriff’s Office arrested one person in January.

According to the report, most of those were drug-related arrests, however the names were omitted.

Recently, the Columbus County Sheriff’s Office signed onto the 287(g) program. This is after being denied acceptance into the program, when CCSO initially applied about 20 years ago, according to Joseph Williams of The News Reporter.

CCSO spokesperson Jenna Jalving said the agreement would allow CCSO to “legally hold individuals under ICE detainers until federal authorities can take custody.” Jalving said that CCSO would only conduct immigration enforcement in jails and not in communities.

Catawba, Carteret, and Union counties have followed suit.

The New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office has not applied for a 287(g) contract. After reaching out to the NHCSO about the changes in immigration policy in March, this is what Sheriff Ed McMahon said:

Thank you for taking the time to express your concerns about the new executive order on immigration. As Sheriff, I want to emphasize that my foremost priority is the safety, security, and well-being of everyone in our community.

To clarify, the enforcement of immigration laws falls under the jurisdiction of the federal government, not local law enforcement agencies. Our primary focus is to ensure that everyone is treated fairly while keeping our community safe so everyone has the opportunity for success. It’s essential that all individuals in our community feel comfortable reporting crimes and seeking help without fear of their immigration status being questioned. Local deputies do not actively enforce immigration laws, and our role is not to inquire about immigration status during routine interactions.

At the same time, I want to be clear that my office will not interfere with federal law enforcement agencies in their operations. We remain committed to cooperating with our federal partners when legally required, all while ensuring that our primary mission continues to be the protection and well-being of everyone in our community.

Sheriff Ed

During this year’s legislative session, the General Assembly voted on a bill that would require all the Department of Public Safety, Department of Adult Correction, State Highway Patrol, and the State Bureau of Investigations to join the 287(g) program, and it passed through the House and Senate with flying colors.

Republican Senators Buck Newton, Warren Daniel, and Phil Berger are the primary sponsors of Senate Bill 153, also known as the North Carolina Border Protection Act. However, it was vetoed by Governor Josh Stein in June.

This would have been the catalyst for broader and stricter interior immigration enforcement. But North Carolina is not the only state trying to set legal precedents to multiply ICE’s personnel numbers by heavily relying on local law enforcement agencies (LEAs).

287(g) and Secured Communities

A patchwork of more unstructured cooperation between law enforcement agencies and immigration enforcement formalized when the 287(g) program went into law.

In an interview with Syracuse University professor Austin Kocher, Writer and attorney Jessica Pishko — whose work delves into the power of the sheriff’s office — said that the Secure Communities Program later reinforced the expansion of immigration enforcement into local policing by creating a “digital ICE presence”.

Pishko said that Secure Communities, a program started by George W. Bush in 2008 and expanded by the Obama Administration, allows fingerprints submitted to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s criminal database to simultaneously be checked against the Department of Homeland Security’s immigration database.

If an inmate’s record indicates a potential immigration violation, ICE could then issue a request, asking the local agency to notify them if a person of interest is being released, and to hold them until immigration enforcement determines whether to make an arrest.

These “ICE holds” are called detainers, and the requested time a person can be held usually lasts up to 48 hours beyond their set release date. Meaning, for example, someone who served their sentence, or paid their bond — effectively ending the state’s custodial responsibility — could still be held until ICE picks them up.

However, according to Albany Law’s Government Law Center, the oldest law school-based center in the country providing nonpartisan research, the cost to house people for additional time beyond their release adds up quickly, and local agencies are left to foot the bill.

There is a government assistance program called the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP) that reimburses counties and municipalities for the incurred costs of incarcerating an undocumented person at their local detention centers; however, those funds go to the county or municipality and not the LEA directly.

According to North Carolina Justice Center’s 2019 report, ICE-issued detainers cost local governments in our state approximately $7.4 million per year.

In addition to heightened costs, Jonathan Thompson, executive director and CEO of the National Sheriffs’ Association, a nonprofit organization that oversees the professional development of over 3000 sheriff’s offices across the country, said agencies responsible for carrying out a detainer are liable for anything that happens to the inmate on a detainer for ICE.

“The Supreme Court has ruled many, many times on this, if they're in the custody of the sheriff, they are responsible,” Thompson said. “However, it just depends upon the agreement. Most of the 287(g) contracts have a negligence clause. [If] your deputy has proven to be negligent in his behavior, that's on them.”

AIC states the Secure Communities program primarily focuses on identifying alleged noncitizens in jails and prisons, and it does not give the acting agency authority to enforce immigration laws, unlike 287(g).

Risky business

Amanda Armenta, faculty Director for UCLA’s Latino Policy & Politics Institute, explores the way immigration policies have impacted low-income migrant populations throughout U.S. history in her work — Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement.

Armenta says public officials, the media, and American society as a whole have constructed illegal immigration as a political crisis that warrants tougher enforcement and more restrictive immigration laws.

As a result, more emphasis on interior immigration enforcement has increased over the years, Armenta said.

“Today, the most salient developments in interior immigration enforcement are the devolution of immigration enforcement authority to state and local law enforcement agencies, attempts by state and local governments to enact immigration restrictions, and the integration of the deportation system with the day-to-day operations of the criminal justice system,” she said.

During her interview with Kocher, Attorney Jessica Pishko said the role Sheriffs play within interior immigration enforcement, in some ways, is connected to the war on drugs.

“The idea behind it was to say, well, if we're arresting people who may be selling drugs, maybe some of them are immigrants, and some of them can be deported,” she said.

According to Pishko, the risk of discrimination that the task force model creates is a troubling aspect of the 287(g) program, especially since she says there has been an increase in task force agreements.

Without fail-safes to protect against potential discrimination, such as the 287(g) steering committee that appears to no longer be in place, Pishko is concerned that this could put immigrant communities in fear of reporting life-threatening crimes to their local police.

“Depending what state you're in, if [an officer] thinks that [a person] might be undocumented, you can't really do anything else, you have to either let them go, or you have to call ICE and wait,” Pishko said. “However, in [their] ICE role, [they] have decided that you might be deportable, and so now [they’re] going to arrest you under that authority and turn you over to ICE.”

NSA Executive Director Jonathan Thompson said from a sheriff’s perspective, it comes down to asking themselves one question: Did I do all I could for my electorate?

“If you're in the business of public safety and security, you fail once, and you take a hit you might never recover from,” he said.

“I think their perspective is, I can't fail my community, and if it means being hyper vigilant and constitutional, because there is still the Constitution they have to uphold, there are a lot of elements they've got to honor.”

Sanctuary states and the Power of the Sheriff’s Office in the context of border security

Eleven states and the District of Columbia have sanctuary policies that limit law enforcement's involvement with federal immigration enforcement. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports that states and localities self-identify as sanctuary jurisdictions, but since there is no federal statute defining exactly what sanctuary policies are, how these policies are observed varies by jurisdiction.

According to Albany Law School’s Government Law Center, "state and local governments make four kinds of choices about immigration enforcement:

- Should they use their resources (personnel, time, and so on) to participate in federal enforcement activities?

- Should they share information about noncitizens with federal authorities?

- Should they detain noncitizens at the request of the federal government?

- Should they grant federal immigration agents access to physical sites controlled by the state or locality?”

According to CRS, the two most common variations of sanctuary measures gaining attention from the Trump administration are ones restricting the exchange of information between LEAs and immigration authorities, and ones that prohibit LEAs from complying with detainer requests.

DHS and conservative organizations argue that sanctuary policies may violate the 10th Amendment and the supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution, establishing federal law as the supreme law of the land. In May, DHS Secretary Kristi Noem asserted that sanctuary policies undermine federal immigration laws by giving states and localities the green light to aid in the refuge of undocumented migrants.

According to CRS, some dissenters argue that when LEAs are able to cooperate with immigration authorities, it provides a type of safety net for field agents.

Instead of trying to identify and arrest people in unpredictable settings, supporters of 287(g) argue that agents are safer identifying people for removal in a so-called low-risk setting such as a jail or prison.

Some who support sanctuary policies from a practical standpoint don’t approve of municipal resources being used to aid in federal matters. Other argue from a moral perspective, saying that sanctuary policies discourage the separation of families and unnecessary arrests of people with minor or no criminal background.

As stated by CRS, “defenders also maintain that constitutional principles of federalism allow states to choose not to participate in federal immigration enforcement activities.”

But since the reverse is also true, Pishko is concerned that many organizations with deep ties to the Trump administration, like the Federation for American Immigration Reform – an organization that advocates for much stricter immigration policies — and Border 911 - a nonprofit founded by White House ‘Border Czar’ Tom Homan — will try to maximize their appeal amongst more conservative sheriffs.

And given the fact that right-leaning sheriffs in sanctuary jurisdictions in particular are adopting the ideology that they should have full authority to determine whether or not they cooperate with ICE is particularly troubling, says Pishko.

Pishko said these anti-immigration organizations may lobby with those deeming themselves constitutional sheriffs; bringing about what she deems are dangerous precedents through a series of sanctuary lawsuits.

“The ‘Constitutional Sheriffs’ movement has done this very well. Their greatest achievement is sort of persuading people that you can't make laws about sheriffs. We're the highest law, etc, etc. It's just kind of not true,” she said.

Where sanctuary laws prohibit ICE from working with local LEAs

Sanctuary jurisdictions have been on Trump’s radar since his first term. As evident in 2017, when he signed Executive Order 13768 Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States, which has been criticized for the interior immigration enforcement measures playing out now in his second term.

Pishko said there are some lawsuits floating under the public’s radar aiming to take this a step further by legally sealing the fate of sanctuary jurisdictions; and making current anti-immigration measures (like E.O. 14159 “Protecting the American People Against Invasion) nearly steel-proof to any rollbacks that a new administration could issue.

Earlier this year, the Department of Justice filed its first lawsuit, targeting sanctuary jurisdictions, against the state of Illinois, Cook County, and the city of Chicago, where LEAs are prohibited from participation in immigration enforcement.

The complaint alleges that sanctuary policies impede the federal government’s ability to enforce immigration laws.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit think tank researching economic inequality, sanctuary laws do not seek to restrict or impede federal immigration agents from carrying out their duties.

EPI states that sanctuary policies clarify what the federal government cannot do — and that is to compel lower-level jurisdictions to use their own resources to aid in immigration enforcement.

Another case under Pishko’s microscope is a lawsuit taking place in Washington state against the Adams County Sheriff’s Office and Adams County, filed by Washington state Attorney General Nicholas Brown.

In the lawsuit, Brown alleges that ACS deputies were violating the ‘Keep Washington Working Act’ since 2022, by jailing individuals based solely on their immigration status.

The Adams County Sheriff’s Office retained lawyers from the America First Legal Foundation, a nonprofit founded by top Trump aide Stephen Miller.

AFLF states, “the Keep Washington Working Act designates Washington State as an illegal sanctuary jurisdiction, which contradicts federal law.”

Prosecuting Attorney Joel B. Ard, who is representing Adams County, wrote in a letter that the county simply wants to cooperate with federal law — suggesting that the state’s sanctuary statutes prohibit the county (and theoretically the sheriff) from doing so.

Pishko said, “I'm concerned, if it gets to the Supreme Court, that the Supreme Court might say these laws do violate the Supremacy Clause, even though they theoretically don't.”

According to the National Immigration Forum, there are no legal grounds to prove state and local officials are acting unconstitutionally when deciding whether to participate in immigration enforcement, or to what degree they choose to cooperate under sanctuary policies.

NSA Executive Director Jonathan Thompson points out why some sheriffs, particularly those in sanctuary districts, see it fit to cooperate in federal immigration enforcement — saying the decision should ultimately be left up to local governments.

“I think the sheriffs need to have the independent authority to decide whether they support the federal government's need to contain or hold individuals. It's a local government prerogative,” he said.

But like Pishko, Thompson said ultimately the decision to require local agencies to enforce immigration laws would be up to the Supreme Court.

“The vast majority of these sheriffs who have come up through law enforcement, that's their training, that's their ethos, that's their knowledge and expertise,” Thompson said. “And they've always been taught you have to protect the community. So when they're told you can help the FBI, but you can't help ICE. You can help DEA, but you can't help CBP [Customs and Border Protection], how is that — How is that, right?”

Thompson said at the political level, this gives sheriffs the power to pick and choose what they want to support, causing a conflict between state law and the federal responsibilities of immigration enforcement.

Adding that both ICE and local law enforcement are in some ways working towards one goal: reducing crime.

Costs and concerns

Thompson said one thing people, especially journalists, don’t ask sheriffs about enough is the challenge of policing people they live and work with so closely.

“Arresting responsibility is 100% done by your neighbor. Think about that,” Thompson said. “[Sheriffs and deputies] know the people that they're arresting most likely. Half the sheriff's offices are smaller than 50 sworn officers. These are their neighbors.”

There have been 28 deportations in North Carolina since January. Five took place in the Raleigh/Durham area, and the rest happened in Charlotte.

Although Charlotte-Mecklenberg County does not have a 287(g) agreement, four surrounding counties do. But an ICE arrest that happened near a local school in Charlotte-Mecklenberg County on May 12, has educational institutions there feeling susceptible to more ICE raids.

This incident — which took place near Charlotte East Language Academy, a full Spanish-language immersion magnet school — demonstrates just how targeted these arrests can be.

More importantly for advocates, it demonstrates the trauma all of this could cause in the community.

Dr. Amanda Boomershine, a UNCW Spanish professor and leader of the university’s Latino Alliance, said there have been deportation cases in New Hanover County.

But she said, “it's kind of hard to define who is being targeted for immigration enforcement right now,” since it has extended to people without legal status who have not committed crimes in the U.S.

“We can't even understand the situation that people are being put in,” she said. “[This] is extremely stressful for another adult in the family, who then takes over the primary role of caregiving and financial support for the family. And then it's also traumatizing for children, as well as loved ones here and in their home country, who were left worrying.”

Boomershine said we run the risk of dehumanizing our neighbors when we only focus on one aspect of their identity.

“Sometimes when we talk about immigration enforcement, we just kind of look at people as numbers or undocumented people, or, you know, criminals,” Boomershine said. “I think we run the risk of dehumanizing the situation when we don't learn about each individual person and their story.”

Additional Resources

- View the full conversation between Jessica Pishko and Austin Kocher here.

- Find the most recent data on ICE arrests, detainers and removals from the Deportation Data Project here.

- Fact sheet on the "Mass Influx" declaration.

- Government Law Center's explainer on 287(g), and LEAs agreements with ICE.