Warning — This report focuses on sexual assault, so some readers may find parts of this story triggering. For the safety of the survivor featured in this story, WHQR has kept some names and identifying details out. The alleged assailant in this story is referred to mostly as the "associate."

Wilmington is a city that offers many unique experiences, says 22-year-old Barbara Espino-Corvera, a nursing student at a local university. From the beauty of the coasts, to the fantastic art, historic architecture, and lively community — these are just a few reasons why she loves calling Wilmington her home.

Espino moved to the United States from Mexico City in 2020, and says one of the most noticeable differences between her life here in the states and growing up in Mexico is a sense of safety.

“I love my country, but unfortunately, right now, it's just going through so much violence in general,” Espino said. “Especially as a woman right now, it's scary to live there, like you never know what's going to happen. You can live in the safest place, and you still just don't know.”

Espino encountered dangerous circumstances back home, although she asked WHQR not to publish details to protect her safety. She said she had to leave Mexico and live with her father in the States.

Attending nursing school in Wilmington with aspirations to be a pediatric surgeon, and she was sure she’d escaped much of the gender-based violence women in her home country are constantly subjected to.

“So I think living in Wilmington, being able to walk on the streets — also kind of dangerous — but it's nothing compared to how it is in there,” she said.

But even though Wilmington is relatively safe, Espino still couldn’t escape violence against women.

Espino tells her story

Though Espino never considered herself much of a drinker, or much of a party-goer these days, coming of age while under quarantine during the COVID-19 Pandemic made her urge to get out and socialize much stronger.

She took every opportunity she could to get out of the house once she met a group of women, who would become her primary friend group. Espino said they were like her anchor to Wilmington’s social scene.

“I went from not really having friends because of the pandemic in Texas, like I arrived and they closed everything down, so I was not able to really talk to people or go out or make friends, really,” Espino said. “So when I arrived to Wilmington and then I started having friends, I went crazy.”

Then, one night in 2023 turned the world as she knew it upside down.

“Something that happens in Wilmington, a lot that I've noticed is being roofied at the bars. I think it happened to me this one time,” she said.

On that night Espino had gone out to a local bar downtown with her friends. Later on, a male associate of the group who Espino only encountered a few times before that night, arrived at their location.

“So what I think happened, or how I got roofied that night is this guy had a rum and coke. I don't drink sodas, but I have never tried a rum and coke,” she said. “He had it in his hand. He was like, ‘Do you want to sip?’ And I tried it. Didn't like it. Gave it back.”

Espino had one more drink after that — a Gatorade shot — and she said, “after that, [I] completely and absolutely blank. I don't remember anything from that night.”

“We were supposed to go to one of my girl's house,” she said. “We had our stuff in her apartment and stuff to go back there. The plan was for all of us to sleep in that apartment that night. I wake up the next day and I'm in my apartment. So I was like, odd, and then I look around and there's like, a broken condom on my floor.”

Espino was further startled the next morning, after her roommate informed her that she seemed intoxicated when she came in that night. He could hear her stumbling through the hallway into the kitchen, where she dropped a pitcher of water on the floor – leaving a large puddle in the middle of the kitchen the next morning.

Her roommate confirmed with Espino that he could hear her that she was possibly having intercourse in the next room.

This prompted Espino to reach out to her friends to find out what happened the rest of that night, and they told her that she went home with the male associate who had offered her the rum and coke.

“That makes no sense,” Espino told them. “Why would you let me go home with him?”

The only answer her friends could offer was that they thought she was fine, and they were told by the male associate that Espino asked him to take her home. So, ultimately, they did not think anything was wrong when she left that night with her alleged assailant.

“Maybe I wanted to go home and he drove me here, or whatever,” Espino said. “I didn't know what happened. I really could not remember anything.”

Espino said this is when she suspected she had been drugged.

“When you black out,” she said. “You have flashbacks, like you remember some stuff, especially, like, if you had sex. You would remember, and I could not remember anything.”

Espino reached out to the associate through Snapchat to seek more answers, and based on Espino’s account of their correspondence, this was his response:

“‘You were begging me to have sex. So I did and just left. I'm so sorry. You were just very insistent,’” he told Espino.

Espino said she was confused, she blamed herself. That same day, she called her partner and confessed that she may have slept with someone else.

Later that day, Espino shared what happened to a coworker, who explained to her that she may have been taken advantage of. Her coworker said since she was unconscious and unable to give consent that she should take legal action.

“So he kind of took me out, sat me down, and he [said], ‘what happened to you, it's called assault here. It is not okay. It's not your fault.’”

The challenges of reporting assault

Espino’s coworker suggested that she go to law enforcement before too much time had past, but he left that decision up to her. She decided to contact the Wilmington Police Department, but she said her experience was not a positive one.

“I called the police, and they were incredibly dismissive,” Espino said. “They could not care less.”

Another reason why Espino chose not to report her assault is because she was concerned about possibly re-traumatizing herself after having to repeat her story multiple times.

Espino said the officer she spoke with misinformed her about having to pay $500 out of pocket to have a rape kit performed, which is normally offered for free.

Ultimately, Espino decided not to get examined due to the cost she thought she had to pay — and, more importantly, she felt like law enforcement did not care.

WHQR confirmed with WPD's Public Information Officer, Lt. Greg Willet, who said since a rape kit is part of the evidence collection process there normally is no charge for this service. Chelsea Croom, the Program Director for Coastal Horizons’ Rape Crisis Center also said a rape kit should never cost a survivor.

“A rape kit covers the visit to the ER, the kit being opened, the evidence being collected, any blood samples being taken – it's usually always covered,” Croom said. “The only time that something may not be as if it if there are injuries outside of the rape kit.”

According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, one in five women and one in 71 men will experience sexual violence in their lifetime, yet 63% of sexual assaults are not reported to law enforcement.

This is why Espino is telling her story she said, because sexual assault happens too often and she wants to raise awareness of the issues and resources for survivors.

“For some reason, when you're a victim of sexual assault, or any sort of like gender violence, it makes you be ashamed of yourself,” Espino said. “It makes you want to hide, makes you want to be apart from people. But you need people. You need support. You need help.”

Community resources

There are many national resources for survivors online like the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, National Center for Victims of Crime, and National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC).

Locally, Coastal Horizons’ RCC offers one of the most comprehensive support services in the Cape Fear Region, with a 24-hour crisis line, EMDR-certified therapists, and victim support advocates.

“We go with them to law enforcement interviews. Should it go to court, we're going with them. If they have any other needs that we're unable to help meet, we're going to do warm handoffs and make sure that they have the resources that they need to move forward and do better,” said Croom.

According to Croom, Coastal Horizon’s 2023-2024 Annual Report shows the number of incidents in New Hanover County stood out from other nearby areas.

Sexual violence is a “pervasive issue in this area,” Croom said referring to New Hanover County. “I think people tend to think, if they don't talk about it, it's not happening. It's happening right here and in our surrounding counties.”

As of 2025, New Hanover County has a population size of 244,988, Brunswick follows closely behind with 174,076, Pender County has a size of 74,167, and Duplin has a size of 50,692.

“So in the fiscal year of 2023 to 24, we had 82 hospital calls. That is just New Hanover County. There are many more in the other counties as well.”

Coastal Horizons’ RCC provided Brunswick County with 17 hospital responses and 45 victims of sexual violence sought services; 12 hospital calls were reported and 16 victims sought services in Pender; and one hospital response was reported in Duplin and seven victims reached out for services.

“And then in New Hanover County, we saw 202 victims of sexual violence,” Croom said. “That does include family members. It does include secondary survivors, friends, intimate partners. And then our clinicians provided 288 hours of counseling to survivors of sexual violence.”

Croom says while she thinks most people try to be trauma-informed to some extent, how someone engages in conversation about trauma varies greatly from person to person.

She says a few ways our society can get on the same page is to start by providing support for people who have experienced sexual violence and make sure their voices are heard.

Croom says to make changes on an individual basis, people can engage less in victim blaming or making light of sexual assault and victims.

“I think educating ourselves is the best thing. I think not avoiding topics because they make us a little uncomfortable is a really good thing. Primary prevention, talking to kids about how to be safe and how to not perpetrate, how to recognize signs of bullying, because that's often where it starts,” Croom said.

Law enforcement is one aspect of our society that can greatly impact whether or not a victim moves forward with reporting their incident or not.

“Law enforcement has a job to do, so they have to interview, and sometimes they're asking questions that don't sound positive or nice, but that's because they're trying to investigate a crime, and so that can feel really daunting,” Croom said.

Croom added that it is not only the fear of not being believed that weighs heavy on many sexual assault victims, but it is also the fear of the unknown once entering into the legal process.

“I mean, a victim has to testify most of the time in the trial, and so that means being cross-examined by a defense attorney. And so that's intimidating, having to go up in front of a jury,” Croom said. “So I think there's like, there's fear of the unknown, there's fear of all of the steps that it's going to take. Some people just don't want to even deal with that.”

WPD's response to calls for justice

Last year, Cassie Payton, a sexual assault survivor turned community advocate, started a petition that calls for reforms to the way the Wilmington Police Department responds to crimes of sexual violence.

Payton even held a protest at WPD’s headquarters in December, and advocated in front of the Wilmington City Council in February.

Espino attended the protest to stand in solidarity with Payton and the many victims of sexual violence, whether they choose to heal in silence or advocate within the community.

“I think it all started because of a Facebook post,” Espino said. “She posted what happened in a girl's group, and I kind of [saw] how unfair police were to her in her case and how dismissive they were.”

Espino interacted with Payton in the comments of that post and was astonished by the many responses.

“The fact that in that single Facebook group there were hundreds of comments saying the exact same thing, that's crazy. This is hundreds of women being abused and hundreds of men abusers still out,” Espino said.

Here is what is included in Payton’s petition, which now has over 10,000 signatures:

1. Mandatory Timelines for Evidence Collection: Require that crime scenes in sexual assault cases are examined within 48 hours of reporting and that identifiable perpetrators are contacted with the same urgency.

2. Victim-Centered Training: Implement mandatory trauma-informed training for all officers handling sexual assault cases to ensure physical and emotional safety for survivors.

3. Accountability Measures: Establish transparent procedures for investigating departmental delays in sexual assault cases.

Payton closed by saying, “My experience is not an isolated incident—it reflects a broader need for systemic change. Survivors who come forward should be met with urgency, protection, and professionalism — not delays that compromise their cases.”

WHQR sat down with Lieutenant Kevin Tully and Captain Rodney Dawson from WPD’s Criminal Investigations Division — which oversees cases involving violent crime, property crimes, fraud, and sexual assault — to get their responses to Payton’s suggested reforms.

Timeliness

“When a crime is alleged, you know, the timeline becomes important,” Tully said. “Did the victim tell a friend? Did they report it? Have days gone by? Has it happened in the past? Is there something that I can use to make that timeline consistent?”

Tully said in many cases, survivors may not divulge certain details of their assault because they may find it uncomfortable or embarrassing to talk about, or they may not remember. However, he said not having all the information pertinent to an investigation can possibly make the process take longer.

Dawson said, directly in response to one of the reforms Payton listed in her petition, that the 48-hour mandatory timeline could potentially be compromising:

“There’s certainly occasions where we either cannot access the crime scene, we don't know where the crime scene is, and to put a mandatory time frame on that potentially could hinder a case if we don't meet that time frame that we've now established in policy.”

If sexual violence has occured, and the victim does not feel comfortable reporting to law enforcement, the detectives said it is best to tell someone they trust as soon as they can.

Both officers said WPD treats sexual assault allegations as a top priority, and said they try to respond in a timely manner.

However, Tully holds the view that most people, regardless of what crime has occured, have an exaggerated expectation of the investigation process, which mostly stems from legal dramas like Law & Order.

“There's a lot of crime dramas on television that people you know have been through enough jury trials to know, everybody's sitting there waiting for the DNA test kit in the car, and Joe Blow Pops out… and that's not realistic,” Tully said. “So they don't typically know forensics and the stuff that's collected to prove a case or that has an evidentiary value in it.”

Tully said a myriad of questions arise at the start of a sexual assault investigation, and that directs them in their search for evidence – which can be anything from text messages, clothes that were worn at the time of the incident, to sexual assault evidence collection kits.

“There could be other factors involved, other objects involved, the presence of any kind of bodily fluids. [Also,] any kind of injury anywhere else on the body, bruising, lacerations, cuts, abrasions, anything like that, and any other type of medical factors, you know, temperature, blood pressure,” Dawson added.

“You know, it's just the accusation, but then we build off of that, and depending on where the story leads, that's how we would respond, you know, and what resources we would need. You know, there's 100 scenarios,” Tully said.

Executing search warrants

Both WPD officers said the amount of evidence that must be collected can seem insurmountable to survivors when going through the investigation process.

However, the more viable evidence they can collect, the stronger their request is for a search warrant, which Tully said can take months:

“And what a search warrant does is it allows the police to pretty much invade somebody's privacy. You have a right to privacy, but in this particular case, if probable cause exists that a crime may have happened and there's evidence to support that, then a judge has the authority to give a court order a document that we swear to give us the right to search and violate someone's privacy.”

Dawson added that there are certain limitations WPD must abide by when executing a search warrant.

The forms must go into great detail about what specific evidence they are looking for, where they plan to look for it and how; the warrants must be thorough enough to gain approval from a judge, Dawson said.

“We can't look for anything that was outside of the scope of what we were looking for, if we violated something that could jeopardize the entire case,” he said.

Being trauma informed

Tully said, “it takes a really good detective to know what questions to ask to start getting that information to build that much bigger picture, to help the case.” But he said the detectives at WPD are trained to be trauma-informed as well.

Dawson said some of the mandated trauma-informed training that Payton asked for in her petition is already in place.

“These officers, they go through training, and then on-the-job training as well. But they're, they're not naive to the point where they have no information when they go in there and talk to somebody,” Dawson said. “But as far as mandating what a procedure should be, I have a problem with that, because every situation is different, and when a report comes in, we allocate the necessary steps, and based on the information that's reported, and we build off of that.”

Tully said during his investigation process that he “[tries] to limit the initial interview with the victim, because there's a lot of time trauma involved. And as far as the investigator goes, we like to set up an appointment after the fact to bring you in a more comfortable setting. Sometimes you have advocates with you.”

Tully also said most officers who respond to the initial report of sexual assault have some sort of trauma-informed training, but they can also lean on the patrol supervisor or senior officers if they ever need assistance.

Both WPD officers believe there is a fine line to walk between investigating a victim’s claims and preserving the rights of the accused.

“So that's our ground rules that we have to play by,” Dawson said. “And you know, sometimes, victims feel that suspects have more rights than they do, and it sometimes seems that way, but they have the same rights as everyone else, and we, as government officials, have to abide by the Constitution. It's the guiding principle for what we do.”

Reporting Sexual Violence

Tully, Dawson, and other professionals mentioned in this story agree on at least one thing — there is no set procedure that can guarantee a specific outcome for every sexual assault investigation, usually because these cases can vary greatly, or oftentimes incidents can go unreported.

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center reports that 63% of sexual assaults are not reported to police. According to NSVRC, reporting a rape or any form of sexual assault can be a daunting task for survivors because of the stigma associated with this type of crime.

Croom, Coastal Horizons RCC Program Director, said incidents also go unreported due to many survivors’ fear of not being believed. That's despite the fact that cases of false reporting of sexual assault range between 2 and 10% — potentially lower than any other violent crime, she said.

Another factor to consider is that, in many cases, the perpetrators are family members or someone highly respected by the survivor, which Croom said makes that fear even greater the closer to home the threat is.

“There's a lot of different things, I think, that survivors feel when it comes down to reporting to law enforcement,” Croom said. “If you think about it, a survivor coming forward and telling their story once is hard, but oftentimes what we're seeing is that they have to tell their story a few times, and that's re-traumatizing. And then stories change, because trauma affects the brain. So then they feel invalidated.”

There are a lot of uncertainties after someone chooses to seek a legal remedy, Croom said. This is why she recommends people who have experienced a sexual assault have a victim support advocate to walk them through the legal process.

“Law enforcement has a job to do, so they have to interview, and sometimes they're asking questions that don't sound positive or nice,” Croom said. “But that's because they're trying to investigate a crime, and so that can feel really daunting. That's why having a victim advocate in the room is really important, because we can help support through those conversations.”

“I think there's like, there's fear of the unknown, there's fear of all of the steps that it's going to take. Some people just don't want to even deal with that. They would rather heal in their own way,” she said.

What survivors should know

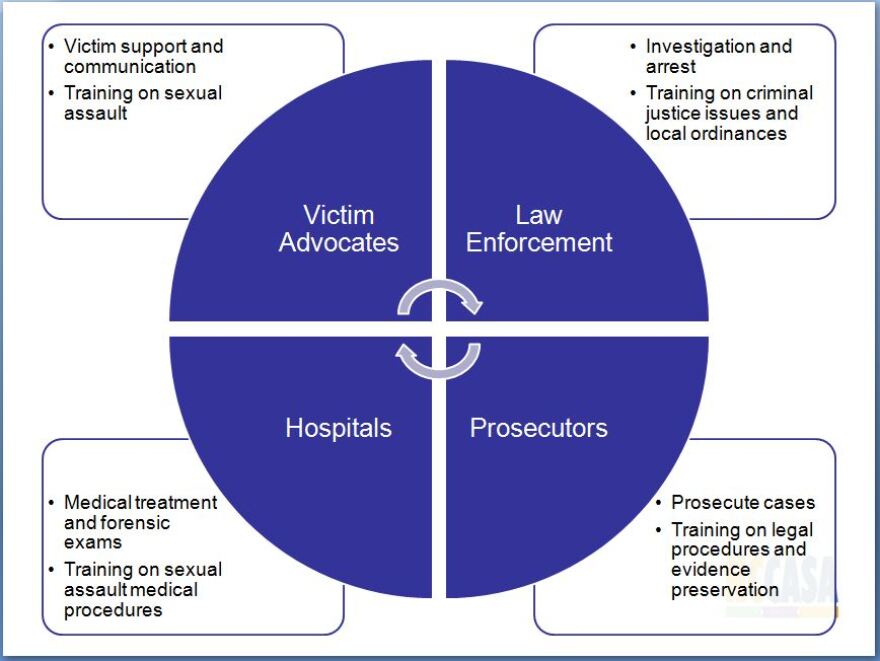

(J. Engelking, S. Florman. (2015). Sexual Assault Response Team Starter Kit: A guide for new SART teams, Sexual Violence Justice Institute).

Executive Director for the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault (NC CASA) Monica Johnson Hostler said there are a few options survivors have if they are considering reporting, but ultimately that decision is left to their discretion.

In North Carolina, survivors have the option to report and move forward with the legal process, or report anonymously, Hostler said.

The latter option allows for evidence collection immediately after an incident, however, officers would refrain from starting a criminal investigation using that evidence until the survivor is ready to move forward.

Whichever option is best suited for an individual, the process of beginning the evidence collection process is the same.

Hostler says a survivor can go directly to an emergency department to have a forensic evidence collection kit performed. They can also call law enforcement, who can transport them to a hospital, or meet them there to collect the kit.

The third option is reporting through a rape crisis center, and then an assigned advocate can meet them at a hospital for evidence collection.

“I would tell a survivor that the choice is really theirs. Both of these are viable options, but neither of them guarantees that their case will be prosecuted in the court of law,” Hostler said.“Because it's a felony, it's the state's case, so the prosecutor has the final decision on if that case will be prosecuted. That's the most difficult thing to explain to a survivor.”

Hostler said how an agency chooses to investigate and their timeline throughout the process depends on that specific agency.

“If it's a large department, they may have a sexual assault detective or investigator [and] that is their only job,” Hostler said. “So they may be responding very quickly. You have other law enforcement officers look[ing] at all cases, so it gets in their queue. How they investigate is certainly up to each agency based on their capacity.”

Though there is no set time frame for investigations, there are victims’ rights that officials must acquiesce. For instance, law enforcement and prosecutors must inform survivors about the status of their case, Hostler said. They should also provide a victim impact statement.

“That happens through your prosecutor's office, or the prosecutor's office has a victim witness assistant who sends them paperwork. Sometimes police will deliver it too, but that's where they are writing down what happened to them [and] the impact,” she said.

“Of course, they should also be made aware of Crime Victims Compensation,” Hostler added. “Meaning, if they have any lost wages, medical bills, all those that also legal process, that there's paperwork that they should be provided, they have the right to confidentiality, and then, of course, for us, they have the right to free support services through our rape crisis centers. So those are state rights.”

NC CASA works with the Justice Academy to help set the standards of trauma-informed training that law enforcement is required to have. Though Holster said, “there is no current training standards that require them to be consistently trained, and that has been a priority for me and other advocates in our state.”

Cultural shift

Hostler said this signals a step in the right direction, however the stigma surrounding sexual assault is harder to mitigate – much of this change starts at the local level, she said.

“We can train people, we can work with people, but the culture does require a shift. That doesn't happen overnight. It requires constant support,” Hostler said. “It’s one Police Department at a time. It's one hospital time, one DA's office at a time.”

“There is not certainly a culture shift of believing survivors at every agency that absolutely does not exist, because, like I said, it requires a commitment, a long-term commitment, and an institutional belief that we're going to believe survivors,” Hostler said.

Croom agrees, saying one of the best ways to support someone who has experienced sexual violence starts with believing the victim:

“I mean leaning in, listening, not asking intrusive questions, validating feelings, if we lean into that and really understand that this is a hard thing for anyone to talk about or to admit that has happened to them, then we can really start understanding and believing and opening the dialog. Hopefully, by furthering the dialog, we can prevent further instances from happening, because we're educating the community.”

As for Espino, she says it is important for people to understand the power of a no.

“A 'no’ needs to have more power, period,” Espino said. “That should be it, I say no and nothing happens.”

Resources for Survivors

- Coastal Horizons Rape Crisis Center - Call 910-392-7460 or email supportrcc@coastalhorizons.org to speak with a counselor.

- NC CASA Survivor Resources

- NC Council for Women & Youth Involvement

- Rape Abuse & Incest National Network

- National Center for Victims of Crime