NEWTON — Book battles have become a regular feature of school board meetings across the country, as parents’ rights groups share tips on finding sexual content and other offensive material in students’ reading material.

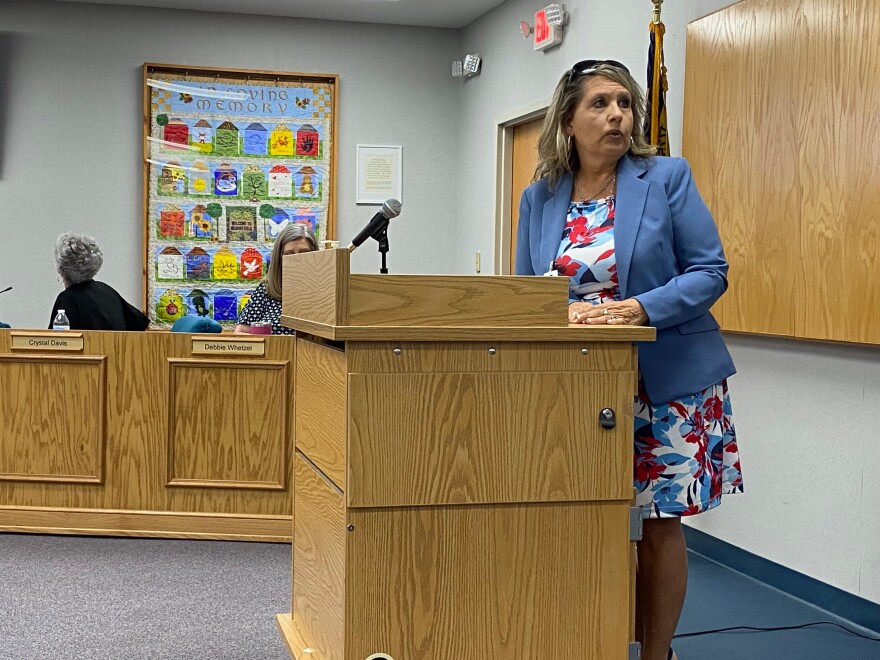

In Catawba County Schools, there’s a twist: The woman who has requested that 25 books be removed from school libraries was elected to the school board last fall. Michelle Teague, cofounder of Mama Bears of Catawba County, now presents her case for removing school library books, then joins the board in voting on her requests. Recent decisions have split 4-3, sometimes tipping for Teague and sometimes against.

Catawba County Schools serves about 15,500 students, sharing the school-age population with separate districts for Hickory and Newton-Conover schools. But the small district is drawing regional and even national attention for the scope of its struggles over what’s appropriate for public schools to put on shelves.

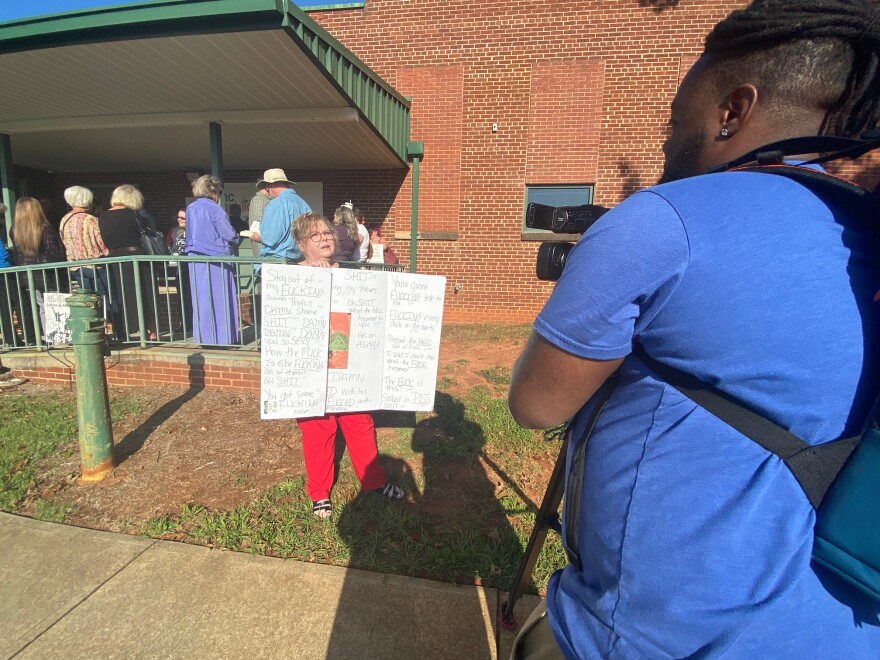

These days half a dozen sheriff’s officers stand guard when the school board meets at the district office building in Newton, where overflow crowds of sign-bearing activists and Charlotte news media show up an hour before meetings.

On Monday, at a special meeting to consider whether Tiffany Jackson’s young adult novel “Monday’s Not Coming” would be removed, there were tallies of F-words in the book, prayers and exhortations for the board to follow God’s will and pleas to protect children from vulgar language and sexual content. There was also talk about defending freedom, fighting censorship and helping students understand the difficult world they live in.

And Catawba County’s struggle to find a path forward is just gearing up.

Mama Bears mobilize

Teague says her now-grown children went through Catawba County Schools and she had a grandchild in the school system when Mama Bears was formed. Its Facebook page now lists 676 members, with a logo of a pearl-wearing, teeth-baring grizzly and an introduction saying it’s a " ‘BOOTS ON THE GROUND’ GROUP DEDICATED TO FIGHTING FOR OUR FAITH, FAMILIES, & FREEDOMS!”

Other counties in the Charlotte region have chapters of Moms for Liberty, a national parents’ rights group that started in Florida. Like Moms For Liberty, Mama Bears started out resisting mandates that students and teachers wear masks to protect against COVID-19, and later moved on to book challenges.

What the various parents’ rights groups that emerged over the last few years have in common is a belief that public schools often can’t be trusted to do what’s right for children, whether it’s related to public health measures, talking about race and gender identity in schools or selecting appropriate reading material.

In March 2022, Teague filed requests to have 25 library books removed. One was a picture book about a gay pride parade, which was part of the teachers-only library at her granddaughter’s elementary school. The rest were books she found in middle and high schools. Among the best known are Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner.”

“I believe that we need to raise our kids with some respect and we need to guard them at certain ages. I mean, I do not agree with inappropriate material in the libraries,” Teague said at Monday’s meeting.

On each challenge form, Teague indicated that she had not actually read the books. Instead, as she explained at this week’s meeting, she checked websites such as Booklooks.org, which searches out profanity, violence and sexual content — especially the kind it classifies as aberrant — in books being used in schools the site includes citations of offending material.

Teague told the board she started out by checking those references and filing the challenges, but has followed up by reading the full books as they read the board’s appeals.Freedom Readers rally

As word got out about the book challenges, another local group emerged: Catawba Freedom Readers, dedicated to standing up for access to books.

Kevin Sparks, a retired physicist, is one of the founders. When he started attending school board meetings he says he was taken aback by the hostility of some comments. He says book disputes are often cast as a battle over fundamental moral values.

“I would say two-thirds of the speakers that are speaking against keeping books in schools, in favor of censorship, will bring a Bible to the lectern or will quote Bible verses or will say, ‘Your souls are in peril if you don’t do something about this,’ ” he said.

“From my perspective,” Sparks adds, “this is an assault on public education. And it’s part of the national story that we see happening everywhere.”

Sparks says Freedom Readers has about 100 members who are sworn to protect each other’s privacy unless someone chooses to go public. Members who work for Catawba County Schools are particularly worried about backlash to opposing the Mama Bears, he says.

Still, Kimberly Turk identified herself as a Catawba County Schools teacher when she told the board Monday that the book challenges threaten to turn schools into hostile environments for some students, especially those who might see themselves reflected in stories about nonwhite, LGBTQ people.

“Wanting these books removed from our schools is sending the message that students who are not white, not straight, should not be visible, that their stories aren’t important and that their experiences don’t matter,” Turk said.

“Please rise above the hate and the fear that are becoming all too common,” Turk urged the board. “Keep our schools a place where every child can find safety.”

Board election and challenge process

Four of the seven Catawba County school board seats were on last November’s ballot, and the Mama Bears put up four candidates. Out of 12 contenders, Teague was the top vote-getter, followed by fellow Bears Don Sigmon and Tim Settlemyre. The fourth seat went to then-Chair Leslie Barnette, a retired educator who kept her seat. She’s now vice chair of the board.

That denied the Mama Bears a majority, and set up some interesting dynamics for the months to come.

Meanwhile, Teague’s book challenges worked through the system. First, each school that had challenged books convened committees to review them. Those panels decided to remove four books from middle schools, but to keep all of them at high schools.

While she was still a board candidate, Teague started filing appeals to the district, which meant convening new panels. Assistant Superintendent Lee Miller estimates that educators and administrators have spent a combined 3,200 hours reading books and weighing Teague’s challenges. The district has also spent almost $3,000 buying copies of the challenged books for panelists to read.

“It does take up some time,” Miller said. “We want to be diligent in the process and make sure we’re serving our students and we’re serving parents and the people who have concerns.”

When Teague did not prevail at the district level, she appealed to the school board — which by then included her. And that raised the question: Could Teague legally and ethically vote on her own appeals?

Barnette and board member Jeff Taylor, also a retired educator, argued that’s a bad idea.

“I don’t think it’s appropriate to sit in judgment of a challenge you initiate,” Taylor said in an interview afterward.

“I said it’s sort of like a prosecutor presenting his case and then sitting on the jury,” Barnette added.

But on Aug. 21, when the first two book appeals reached the board, Teague said she would not recuse herself.

“I’m not biased,” she told her colleagues. “I’m passionate about children and their educational welfare.”

The board’s lawyer said the law does not require her to step aside. Barnette made a motion to recuse her but it failed on a 3-4 vote. Teague voted to allow herself to hear her own appeals.

In a meeting that lasted five hours, the board then voted 4-3 to remove “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Pérez and to keep Susan Kuklin’s “Beyond Magenta” in high school libraries.

Tears, prayers and passion

The third challenged book came before the board at a special meeting on Monday. The Freedom Readers had invited Democratic state party chair Anderson Clayton to headline a press conference before the meeting, but they called it off as a crowd gathered and they concluded it might be disrupted.

In addition to the Freedom Reader members, carrying signs saying things like “Dictators Ban Books,” Diana Jimison was there with a hand-lettered sign full of profanity-laced quotes from “Monday's Not Coming.” She insisted that a TV reporter needed to show that sign if he wanted to interview her.

“He said WBTV couldn’t use this sign because of all the words on it,” she said. “This is every word … coming out of the book being discussed tonight. Yeah!”

“Did you read it?” a Freedom Readers member asked.

“I sure did. In four hours I got that book read,” Jimison said. “How do you think I got all the verbiage?”

“Oh, you looked for it, didn’t you? Like the good little pervert you are,” the Freedom Readers member replied.

Once the meeting started Clayton, the Democratic Party chair, got her say during the public comments. “It’s about the freedom to read. It’s about the constitutional right for every student to learn what they want to,” she said. “And it’s about being anti-censorship.”

From people who wanted the book removed from high school libraries, there were appeals to religion. One speaker prayed aloud for God to give board members “clear dividing lines on what is right and what is wrong, on what is evil and what is good.” Another said the debate isn’t about the book: “It’s about the devil. The devil wants our children. He wants to get into their minds.”

Rick Settlemyre, the father of board member Tim Settlemyre, said that “the F-letter word” is in “Monday's Not Coming” 27 times. “How in the world can you let that book be in the hands of your kids?” he asked.

Among those who wanted it kept on the shelves, there were several references to Zahra Baker, a 10-year-old Catawba County girl who was reported missing in 2010 and eventually found to have been killed by her stepmother. They noted the similarity to “Monday's Not Coming,” a story narrated by a girl whose best friend, named Monday, doesn’t show up for school. Adults in the story ignore warning signs about what’s happening to Monday and the story ends with the discovery that she’s been killed by her own family.

Carrie London, the mother of a 10-year-old, cried as she argued for the book to stay, “because our children should know what their friends are going through. They should be able to see and recognize evidence of abuse.”

The only student who spoke was Madelyn Beisler, a senior at St. Stephens High School. She said she and her classmates don’t need to be protected from profanity or uncomfortable material.

“This is my phone,” she said, holding it up. “I can find anything I want to on my phone. So, I mean, if you’re going to put a phone in my hands, why not put a book in my hands?”

Agreement and emphasis

Speakers on both sides agreed on two things: That the content of the story and some of the language made them uncomfortable, and that it reflects a painful reality for teens. They split on which aspect was more important.

Those who wanted to keep “Monday's Not Coming” said high school students need access to books that teach empathy and reflect real life. They noted that none of the challenged books are required reading; they’re just available for those who choose to check them out.

Others took the view of board member Tim Settlemyre, who said there are better ways to make the point.

“Child abuse is wrong, child neglect is wrong, murder of children is wrong. You could have come up with that without all the vulgarity, without all the sex,” he said. “Why was that even … put in there? Was it to normalize it?”

Several people who spoke for removal from school libraries noted that parents who wanted their kids to read “Monday's Not Coming” could buy it or check it out at public libraries.

After 3 ½ hours, the board voted 4-3 to restrict access to students who are at least 18 years old. The three Mama Bears board members voted no, hoping to get it removed.

The path forward

As of this week, the Catawba County school board has weighed in on three of Teague’s challenges, which means there could be 20 or so to come.

Board member Taylor says he worries that the district is becoming known as the book-ban district, despite the fact that the issue seems to be important mostly to activists who don’t have children in Catawba County Schools.

“The time we’re spending on this, we’re not talking about making our schools safer. We’re not talking about how we hire and retain high-quality staff,” he said. “And my concern is if we become known for this … we will repel high-quality staff.”

On Monday, the school board will meet again. One of the things they’ll discuss is a change to the policy governing book challenges. Miller, the assistant superintendent, said they’re considering a new policy that would eliminate the school-level appeal, to reduce the demands on principals and teachers.

Next year the three remaining school board seats are up for election. And there’s a twist: The General Assembly switched Catawba County’s school board elections from nonpartisan to partisan.

The current board includes four Republicans, two Democrats and one unaffiliated voter. In a red county, having party affiliation on the ballot could make it harder for Democrats like Taylor and Barnette to win.

As for Teague, who’s a Republican, she said in a brief phone interview that she knows there’s more to being a board member than removing books from libraries.

“We can’t be just focused on books,” she said. “That’s just one item. There’s a lot of stuff going on with the school system.”

But she quickly ended the call and declined to talk about her other priorities — or what she hopes to see as Catawba County Schools moves forward.