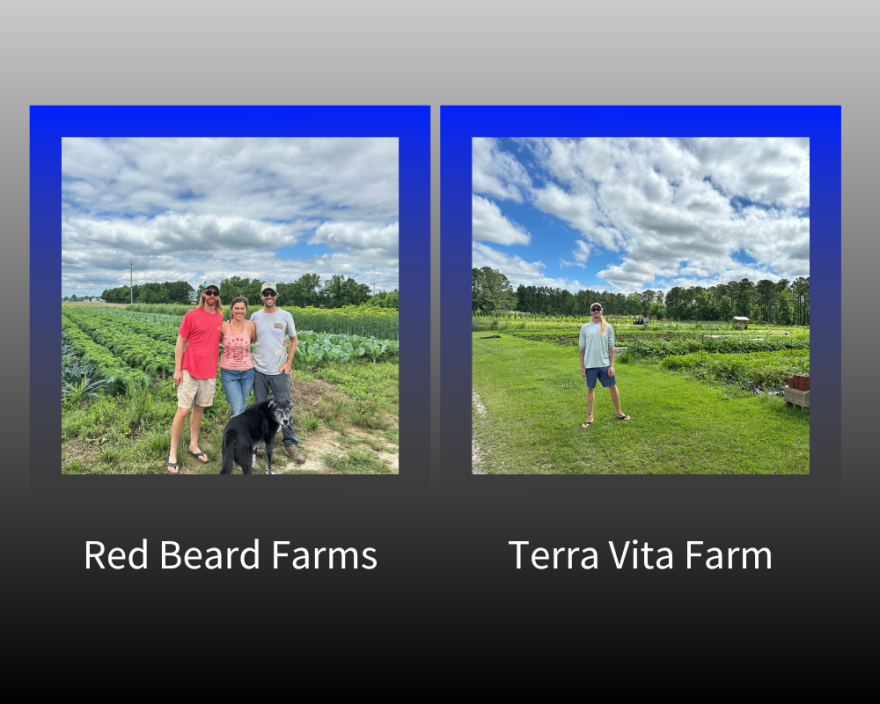

Farmer Michael Torbett of Terra Vita Farm in Castle Hayne, packs a lot of produce into a relatively small 2-acre plot near the River Bluffs neighborhood.

“So we do a bunch of seasonal crops of different things. We do a bunch of flowers, some fruits, a bunch of solanaceous crops. We have a bunch of garlic and onions out there. Our foxglove just started to flower; snapdragons have been beautiful, they always are," Torbett told WHQR.

In the spring and fall, Torbett offers a CSA box — that stands for "community-supported agriculture," where people basically subscribe to receive regular batches of whatever a farm grows. Torbett also sells at the Tidal Creek Farmers Market — and to local restaurants.

“So it's a lot of turning and burning. Once crops are done, we're getting beds prepped and back up and stuff replanted, very labor intensive, a lot of work,” he said.

Red Beard Farms in Pender County, a nearly 18-acre property, is a 30-minute drive from Terra Vita. Morgan Milne is the owner and operator and also sells a CSA for two seasons as well as vending to restaurants and at the farmers market — and, yes, he does have a red beard.

“Yeah, so the name started as a joke. I didn't want to shave for my sister's wedding, and we were starting the farm at that time. And I was like, ‘Oh, if I name it after the beard, I won’t have to shave.’ I ended up having to shave,’” Milne said.

According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, New Hanover has 60 farms, mostly crops, whose market value of products sold is $2.5 million. For Pender, it's much larger: 354 farms produce a market value of $246 million, but these mostly consist of livestock farms, not crops-producing farms like Red Beard.

Milne said it’d be easier to say what he doesn’t grow on the farm, but then he proceeded to list off the dozens and dozens of plants at Red Beard:

“We're into cut flowers, red radish, French breakfast radish, purple kohlrabi, yellow squash, patty pan squash, broccoli, sweet corn. [...] We have slicing tomatoes, plum tomatoes, jalapenos, banana peppers, eggplant. [...] Basil, purple basil, cherry tomatoes, heirloom tomatoes, strawberries, fennel, all three beets, three types of radicchio, iceberg lettuce, red potatoes, white potatoes, gold potatoes…”

Milne said he couldn’t make the farm work this without his wife, Katrin, his employees, and his lead manager, John Gurganus.

“So lucky me, I ran into him, and I said hey, ‘Come check us out,’ and he drove a hard bargain, and three years later, he’s still here," Milne said.

Gurganus laughed and said, “Yeah, the hemp market wasn’t what it was all cracked up to be.”

These farmers say that, for health reasons, it’s important to buy local produce.

“Plants start to atrophy their nutrients; they start bleeding out the minute they're harvested, so produce sitting on a shelf for an extended amount of time really drastically takes away from its nutritional value,” Torbett said.

Milne said that buying local is also about keeping the economy strong.

“You keep the money in the community. And, you know, we're not a big corporation. All of our employees live around here; they spend their money around here,” he said.

Farming practices

Torbett and Milne both say they use organic practices on their farms but don’t go through the process for the official label because of paperwork, time, and finances.

“The last time I looked into it, I think it was $1,500 or $1,600 a year for us to be certified, and if we can do all of the same things without having to deal with the organic inspectors, and then we don't have to tack that extra cost onto our prices,” Milne said.

Torbett said his farm has a naturally grown certification, which is done in partnership with the New Hanover County Cooperative Extension.

Matt Collogan is the consumer horticulture agent there and said they have to have “peer farmers or extension agents come out and make sure that [their] practices are up to snuff with that standard organic.”

Llyod Singleton, the cooperative's director, said Milne and Torbett's polyculture practices help keep the pests at bay.

“When you have a more diverse cropping system, you actually have predators of the pests may be attracted there for some other reasons, so that kind of keeps things a little bit more in balance and does actually reduce the need for a lot of pesticides,” Singleton said.

In addition to pest control, they have to think about things like disease and fungi.

“It always shows up; you’ll see evidence of fungi on some of the older broccoli plants. It's part of the name of the game around here. We're always fighting it. We're never going to win, but we have to tie,” Gurganus said.

Both farmers also use the cooperative to send soil, irrigation, and compost waste samples for analysis.

Gurganus said Red Beard has a high phosphorus level in its soil, which they monitor closely.

“The biggest thing is making sure our pH stays balanced because if our pH dips too low, we'll start seeing a lot of other plant problems,” he said.

These farmers are always battling something. Torbett said his strawberries didn’t make it this year, but he isn’t sure why.

“I don't think our bed prep was great, and we ended up with a lot of disease, a lot of dead plants. Not real thrilled about it. We only got good production for maybe a month, and then everything kind of stopped. At this point, I'm just gonna get them out of the ground and get new stuff planted,” he said.

Mother Nature and resiliency

Of course, weather and climate are always top of mind.

“I am a little bit worried about hurricane season; we are going from El Niño season into La Niña season, so I'm very unsure what that looks like for our fall, but we'll find out,” Torbett said.

For Milne, Hurricane Matthew was one of the first big storms for Red Beard — it wiped out their fall crop.

“And that was our second full year here, and then 2018 would have been our fourth full year, Hurricane Florence, the same thing wiped out our whole crop. So two out of the four, of our first four years, the second half of our season was completely gone, so that made it very difficult,” Milne said.

Torbett said before the Castle Hayne farm, he had one in Rocky Point and lost everything during Florence — and said he can’t rely on loans or a GoFundMe after a major storm hits.

“If there's one thing farming will teach you, it's resiliency. It's nice to have safety nets and people willing to help you when you need it, but those aren't always guaranteed,” he said.

Milne agrees: “You just keep trudging ahead. Once you lose it, it's gone. Typically, in our experience, the community really rallies around you because they want to see smaller farms and have options, obviously, for where they can get their food.”

Collogan said to handle all these factors of weather, climate, pests, disease, and balancing the economics of it all — he’s in awe of farmers like Torbett, Milne, and Gurganus.

“All those folks share some common characteristics: stubborn, but in a good way, hard-working, and just will work until the cows come home,” he said. “They have very strong personalities, and you got to deal day in and day out with environmental conditions and the hard labor that goes into it, and then the business behind it, which, if it's not making money, you're wasting your time.”