An upcoming zoning ammendment will make it legal to build accessory dwelling units on nearly every residential property in Wilmington. They provide many benefits to the homeowner and the community: providing rental housing in established neighborhoods, adding income for homeowners, and maybe providing a home for a new neighbor who can check in on your garden or your pets when you’re out of town.

But building an entire new home is daunting for an average homeowner, who might have little or no experience pulling permits. WHQR asked local expert Roger Gins from the non-profit Back Yard Housing Group to walk us through the process, step by step. His goal is to help homeowners make this dream a reality, for free.

Gins says ADUs are appealing because “There is no land cost to building them, and it creates multi-generational households, which is a very popular solution. It also can add income for the people who are aging in place. And it's a relatively easy process.”

Step 1: Can it fit?

The average ADU in the United States is around 600 square feet, which is about the size of a one-bedroom apartment. In Wilmington, the maximum size is 1200 square feet, which could be a 3-4 bedroom house. But an ADU can’t be larger than half the size of the primary residence on the land.

Wilmington Zoning Administrator Kathryn Thurston says there are strategies to make a larger and more useful ADU despite having a small house: “You could add some living space to your house and then do the ADU above that,” she says.

ADUs can’t be any taller than the primary dwelling if they’re unattached, but attached ADUs don’t have that restriction.

They also can only be placed on certain parts of your property: behind the primary structure, and at least 15 feet away from the rear property line.

Step 1.5: Have an HOA? Your ADU might be DOA

Gins says “Every HOA I know bans ADUs.” Not every neighborhood in Wilmington has an HOA, but most of the newer neighborhoods do. Homeowners might be able to work together to get rid of those bans if they have democratically run HOA boards, but it otherwise may be in the purview of the legislature to stop HOAs from banning this type of property use.

“Oregon won't allow HOAs to restrict ADUs. Same for California,” Gins says. He doesn’t believe this is a high priority in the current legislature, although HOAs are in the hot seat in Raleigh for abusive practices.

All that is to say: if you live in an HOA, check your bylaws to see if you can build an ADU.

Step 2: Draw a sketch, and bring it to the Zoning Department

Once you’ve imagined this ADU in your yard, you’ll need to draw a sketch and bring it to the city.

“All you really need going in is a plot plan of where the residence is going to be and elevation to show how tall it's going to be, because there's a limit of 35 feet,” Gins says.

He recommends pulling a property sketch from the county tax website to use as the basis of your drawing. And at least for this first conversation, Gins says a hand-drawn sketch by the homeowner is “plenty.” This isn't a legally required step, but it's a good way to avoid wasting your time and money to avoid designing something the zoning department can't allow.

Step 3: Design and Planning

Once zoning has taken a look at your sketch, you’re ready to take your plans to the next level. Gins says this is when it makes sense to call in some expert help (like him) if you don’t have much experience with building permits or construction.

“The next step probably will be deciding what specifically your home or your attached adu is going to look like and is it going to be one bedroom, two bedrooms, so forth.”

A cursory Google search reveals hundreds of plans for ADUs of all shapes and sizes. Raleigh even has a fast-track program with plans that are automatically permitted.

Whether you buy plans off the internet for a few hundred bucks, or if you hire an architect for a few thousand dollars, you’ll need to get the sign-off from an engineer, Gins says. “That includes designing the foundation and making sure that the house meets the hurricane requirements.”

Step 4: Permits

Once you’ve designed your ADU, you’ll need permission from the county to build it. You’ll go through New Hanover County for this, whether you live in city limits or not.

“They are also very friendly. And they will go over your plans and guide you for changes,” Gins says. “Then the building department issues a permit to you, rather than each subcontractor.”

You can apply for permits through the county’s portal, and the one to look for is called “Residential Build New Single Family”. These permits cost a minimum of $400 for a detached ADU, or $0.441 per square foot.

Step 5: Financing

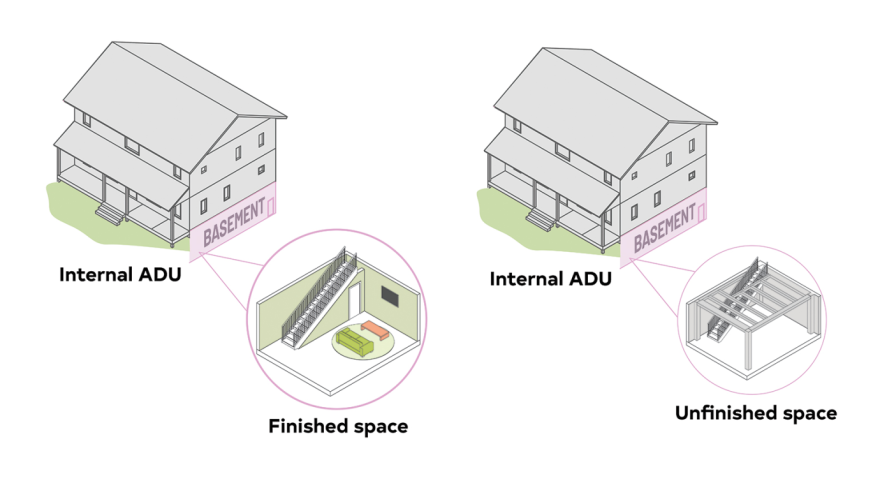

The average ADU costs $150 to $300 per square foot, or $60,000 to $225,000. The less expensive versions are usually attached ADUs that largely re-purpose existing structures, while detached cottages tend to be the most expensive. There are several ways to finance them if you don’t have that kind of money sitting in a bank account, but Gins admits, “That's probably the hardest part of the whole process.”

For federal programs, you can get an Federal Housing Administration loan called 203(k). That program expanded to cover attached ADUs last year, and requires a mortgage on the house and the ADU.

“They will allow you to use 50% of your projected rental income to qualify them for the loan,” Gins says.

But with interest rates as high as they are, taking on a mortgage may not be appealing to the average homeowner. The city of Wilmington has a program that could be used for ADU construction: the Rental Rehabilitation Incentive Loan. It’s a 0% interest loan of up to $200,000 for a rental home that will be rented at an affordable rate, and could potentially be used for ADUs.

At this time, the loan program is primarily used by professional landlords and developers to rehabilitate derelict housing or build ADUs on existing rental properties, but Gins sees a future where regular homeowners might use it for their ADU projects.

Currently, the city loan program has limitations that make it unappealing to many homeowners: it makes it financially very challenging to sell your home during the repayment period.

If you sell your property during the affordability period, which is 5-20 years, depending on how much you borrowed, there will be a recapture of interest at a rate of 10% per year from the date of the original loan closing through the sale date.

That’s an effort to ensure affordability and prevent flippers from taking advantage, but it is a deterrent to homeowners who aren’t primarily real estate investors. Perhaps a Home Equity Loan is a safer bet. But there are many new financing options available, as described by the L.A. Times.

Step 6: Build it!

If this seems like an understatement, it is.

“You need to have realistic expectations, it's going to take a year to 14 months of effort. It's building a small house,” Gins says.

Still, Gins says it’s a process anyone can do, and there are “plenty of resources to assist you going through the whole construction.” Gins has contacts with contractors and subcontractors who can help build the ADU for you.

You’ve got your initial permit, but you’ll need additional permits and an inspection for each phase of construction: the foundation, the framing, electrical, plumbing, and air conditioning. Hiring a builder means having an expert handle those permits for you, along with managing each subcontractor.

Gins says it can be costly to hire someone, but it saves you a lot of headache and labor compared to doing it yourself. At one project he’s involved in, “We're adding at 500 square foot ADU. And we're projecting $140,000.”

If you’re handy enough to DIY, Gins still suggests talking to experts for guidance. “Don't try to do it just by yourself. There's a learning curve, but it's completely doable”

Often, attached ADUs are a bit less expensive, especially if they’re repurposing an existing part of the main structure and just adding an exterior door and a kitchenette. A more detailed cost estimate guide is available here.

Step 7: Moving someone in

Once everything is done and you’ve gone through the final inspection, all you need is a certificate of occupancy from the zoning department. “Once you have that, you can move in, or you can find a tenant,” Gins says. “Don't forget this is in your backyard. Usually, I'm assuming this is an owner occupied primary residence. And so your criteria is going to be slightly different than if it's investment property.”

Some homeowners want to use an ADU to house a family member: either a recent graduate or an aging parent. Others are looking for rental income, so they’ll rent to a stranger. If you’re an aging homeowner, an ADU can offer multiple benefits: adding extra money to your typically fixed income, and adding a neighbor who can check in on you while still giving you privacy.

For renters, ADUs are typically below the market rate for an apartment, while existing in desirable, single-family neighborhoods. And for the city, it’s an added unit of rental housing that doesn’t require additional infrastructure: a win-win-win.

And what about the impact to the neighbors? Gins says there isn’t too much of one. “We have a local example of how successful ADUs can be, especially to property values and how they fit into the community and that's Forest Hills. The majority of the homes in Forest Hills have ADUs, and certainly it hasn't affected the values nor the traffic.”

Forest Hills was one of Wilmington’s earliest suburbs, and its large number of ADUs is an artifact of history. During World War II, thousands of people moved to Wilmington to help build ships for the war, and there wasn’t nearly enough housing for them all. While the Federal government tried to step in with public housing, locals also answered the call by taking in boarders and building garage apartments for new tenants. These low-barrier rentals supported the war effort, and many ADUs in Forest Hills neighborhood exist because of that patriotic call to house workers.

ADUs in the modern area play a similar role in managing the country's affordable housing crisis, and could help create an entry-level housing type that's more affordable than standard 1-bedroom apartments.