This article was published as part of WHQR's collaboration with The Assembly. Find more here.

On the afternoon of June 19, Dyrell Green was brought into the courtroom in shackles, under the watchful eye of no fewer than 12 uniformed sheriff’s deputies and many more plainclothes law enforcement officers who had come to watch the proceedings.

Judge Kent Harrell began the hearing by instructing his bailiffs to confiscate all phones from the gallery.

“If you see a cell phone, seize it immediately, and take that person into custody,” Harrell said.

That set the tense mood in Courtroom 403. On the docket: a motion to dismiss the murder charges against Green and his codefendants Omonte Bell and Raquel Adams. The three are charged in a high-profile double-homicide case that took place in July 2021 at the home of a top executive for TRU Colors, a controversial brewery with a social mission of reducing street violence by hiring active gang members.

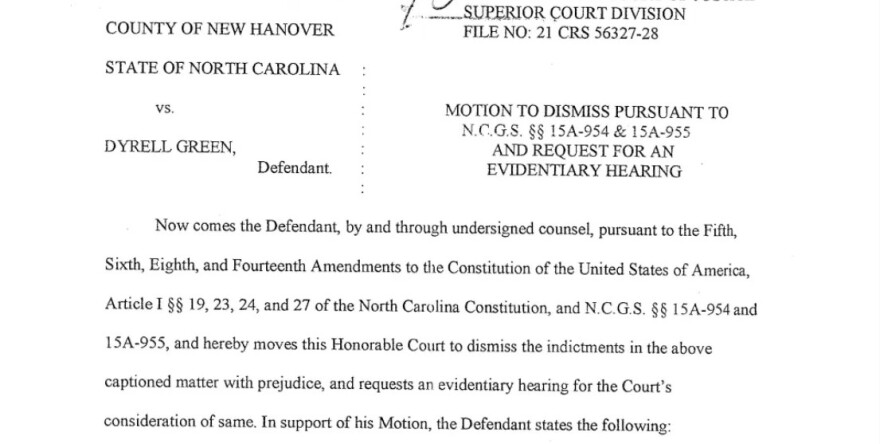

Defense attorneys filed their motion after getting their hands on a PowerPoint presentation from the February 21, 2022, grand jury hearing where Adams, Bell, and Green were indicted— a necessary step in North Carolina to pursue serious felony charges. They argued that the presentation, prepared by New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office Detective Jeremy Boswell, contained potential perjury that violated the suspects’ constitutional right to due process.

That the lawyers had access to the presentation at all is highly unusual because grand jury proceedings in North Carolina are clandestine: no recordings or transcripts are allowed, and jurors are forbidden from discussing what transpired.

As Emily Byrum, Green’s defense attorney, told the court, North Carolina is one of only about 10 states with this level of secrecy. Most state and federal grand jury proceedings have some manner of recordkeeping, although those records are often sealed.

One of the reasons for this secrecy, according to the North Carolina court system, is protecting the reputations of those accused of crimes who are ultimately not indicted. But its effect on the reputation—to say nothing of the freedom—of those who are indicted based on flawed evidence, or even perjury, are often overlooked. And that’s what makes the most recent twist more painful for Green’s family.

Green’s father, Ronald Canty, told WHQR ahead of the June hearing that despite his misgivings about the legal system, he thought there was a very real chance that his son would go free. But that did not happen.

Harrell denied the motion in part because it had very limited case law to draw from because the situation was largely unprecedented. That’s just about the only thing the prosecutors, defense attorneys, and Harrell agreed on.

In North Carolina, the grand jury is a black box. Harrell kept it shut.

But the fact remained, it was opened, however briefly—which has implications beyond the case against Green, Bell, and Adams.

A high-profile double homicide

Adams, Bell, and Green are charged with first-degree murder and conspiracy for the murders of Kordreese Tyson and Bri’yanna Williams, at the house of George Taylor III. Taylor was the chief operating officer for TRU Colors, the for-profit brewery and anti-violence initiative run by his father, George Taylor Jr.

Canty has maintained the innocence of his son since the New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office announced his arrest alongside Adams and Bell in August 2021. He told WHQR that Dyrell was with him on the night of the murders, and disputes law enforcement’s claim that his son was a gang member.

Sheriff Ed McMahon and District Attorney Ben David portrayed the killing as essentially a gang hit. Tyson, officials said, had become a high-ranking member of the Gangster Disciplines (also known as Growth and Development and sometimes referred to by the abbreviation GD), and they claimed Adams, Bell, and Green were validated gang members from a set of the rival Bloods gang. Canty said it was the first he’d heard of his son’s own alleged gang affiliation.

The defense’s argument hinges on a peculiar—and possibly unique—set of circumstances, stemming from a May 9, 2022, bond hearing. According to the defense attorneys, prosecutors had a considerable advantage: They had “access to voluminous amounts of discovery from the [New Hanover County Sheriff’s Office] and opted not to release it to the Defendant” ahead of the hearing.

The discovery process essentially requires both parties to share evidence so neither is surprised by any evidence brought up in the courtroom.

The defense attorneys said they were frustrated by facing evidence they had not yet seen being brought up in this hearing, despite having made multiple requests and a legal motion to release the “exorbitant amount of outstanding discovery.”

The hearing resulted in Green receiving a $1.2 million bond. Canty, Green’s father, said that was functionally the same as denying him bond entirely, as the family could not afford even a 5 to 10 percent down payment to a bail bonding company.

Prosecutors finally released additional material several weeks later, including the PowerPoint presentation Detective Boswell had created.

After reviewing it, the defense pointed to Boswell’s claim that Bell had been arrested for shootings in Wilmington. According to the defense, “Detective Boswell was presented a certified copy of Bell’s criminal history and could not locate any record of a previous shooting arrest.”

The defense also said that in both Boswell’s presentation and on the stand, the detective claimed Bell “stated to detectives that he was not going to snitch but did not deny murdering the victims.” But defense attorneys said interrogation transcripts show Bell did deny committing the murder, not just once but more than 70 times.

Nor did Bell say he was with any of the other codefendants on the night of the murder—although Boswell’s PowerPoint claimed he did.

There were also “inaccuracies” regarding the case against Green, the defense motion said—notably two rap videos that Boswell’s presentation alleged were created and posted “after the murders but before [Green’s]” arrest.

The defense claimed, and WHQR was able to verify, that the songs were initially posted as audio tracks on SoundCloud in April, months before the killings.

The videos feature Green, who goes by “Sleepy,” and others brandishing multiple firearms, and the songs contain plenty of violent lyrics, including reference to shooting someone in the neck with hollow-point bullets. Green raps with a drawl that occasionally makes it difficult to parse his lyrics, but one line sounds like “hollows at a n—–’s neck, now I just popped a n—–’s collar” (you can listen at the 0:42 mark).

According to the defense, Boswell’s PowerPoint indicated this was a reference to a wound that Tyson, one of the two murder victims, suffered.

The admissibility of rap and other lyrics in court is also a matter of active legal debate, though increasingly courts are accepting them as evidence. California and Louisiana have passed laws meant to protect artists, and a bill has been proposed in Congress that would provide federal protection, although it hasn’t gotten much traction.

Canty said he has asked his son about the track.

“He said, ‘Dad they took an old tape I made in April of ’21, took it to the grand jury, and said I killed Kory, and made it that I was bragging about it,’” Canty said.

Canty noted the lyrics don’t name Tyson or use his street name, “Thug.”

Canty also told WHQR that he felt the misrepresentation of the publication date was designed to make the song feel more like a confession.

“That was really what got him locked up, because they had no other evidence,” Canty said. “So, how can you get a true bill of indictment on a man—he must have lied about the date, because the grand jury would see the date and say that couldn’t be.”

Whether you call them errors, mistakes, inaccuracies, or something stronger, this is the kind of thing that, in a courtroom in front of a judge or jury, could be grounds for a mistrial.

But because it happened during the grand jury proceedings, we’re not really supposed to know that it happened at all.

The Black Box

In almost all grand jury proceedings, neither the defendant nor defense attorney is allowed in the room—in fact, it is rare that the person named in the indictment proceedings is aware the grand jury is even considering their case until they are arrested or appear in court. The prosecution is also not present, and the proceedings are overseen by a grand jury foreperson, not a judge.

Jurors are only shown the case against a suspect, almost always in the absence of exculpatory evidence. They are asked to consider a lower standard of proof than what’s put forward in a jury trial, too. For those reasons, grand juries almost always indict. Because it’s not public when they don’t indict, exact figures are hard to come by—but many experts say it’s over 90 percent. Federal juries indict 99 percent of the time, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics data.

“He said, ‘Dad they took an old tape I made in April of ’21, took it to the grand jury, and said I killed Kory, and made it that I was bragging about it.” — Ronald Canty, father of Dyrell Green

No one knows what happens in the grand jury except the jurors and one witness, who is usually a person familiar with the case—often, but not always, a law enforcement officer familiar with the case. Everyone in the room is barred from discussing the events of the proceeding and can be held in contempt of court if they do.

And that is what makes the release of the PowerPoint in the Tru Colors case so unusual.

Phil Dixon, an expert on criminal defense who educates public defenders at the University of North Carolina School of Government, said he’d never seen a case quite like it.

“That’s not something I’ve ever seen in discovery,” said Dixon. “There’s probably a decent argument that it isn’t discoverable, or that it shouldn’t have been disclosed in the first place. But once they have it, the cat is sort of out of the bag.”

It’s not clear if including the presentation in discovery was an accident. Given the potential repercussions, it certainly feels that way. District Attorney David’s office has declined to comment on the case. But the question going into last month’s hearing was, now that the cat was out of the bag, what would the court do about it?

"Uncharted Territory"

During the June 19 hearing, defense attorneys Emily Byrum and Jordan Willetts said they had “serious concerns” that the grand jury process had been “tainted by perjury.”

Byrum noted that in federal cases, grand jury records are kept, even if they’re sealed, for a situation “just like this.” The defense attorneys pointed to a ruling from a 1974 federal district court judge that referred to perjury in a grand jury as a “cancer of justice.”

Prosecutor Doug Carricker argued against the merits of the defense’s motion, saying it was “an enormous leap” from mistakes to “material perjury.”

The district attorney, David, focused on the importance of grand jury secrecy.

“There’s probably a decent argument that it isn’t discoverable, or that it shouldn’t have been disclosed in the first place. But once they have it, the cat is sort of out of the bag.” — Phil Dixon, University of North Carolina School of Government

“They’ve never been able to invade the secrecy of the grand jury—they’re stabbing all around it,” David said.

David also called the defense’s motion “slanderous allegations” and said grand jury secrecy cut both ways—preventing the detective who created the presentation from defending himself from accusations of misconduct.

Byrum said her motion to dismiss was a “good faith” complaint based on solid evidence. And, although there’s no record of whether the PowerPoint was actually shown to the grand jury, the defense argued the metadata showed it was prepared right up to the day of the indictment. Byrum said it “defied belief” that it wouldn’t have been used.

David didn’t acknowledge the alleged errors in the grand jury presentation—although he did say the state had plenty of evidence. Instead, he focused on the defense’s “creative attack on the grand jury process” and cautioned against what would happen “if we begin to go down this road.”

Judge Harrell seemed to agree. “If I allow what you’re doing here, what’s to stop every defense attorney [from challenging the grand jury]?” Harrell asked.

Harrell’s opinion is in line with what most judges would say, said UNC’s Dixon.

“That is a sacrosanct rule in North Carolina, that the grand jury is secret, and that you’re not allowed to ask them about their deliberative process or what evidence was presented before them,” Dixon said.

But as the defense attorneys have said, it’s also rare for them to find themselves in this position.

Dixon agreed on that front, too: “Defense lawyers are not willy-nilly challenging grand jury indictments, based on this sort of challenge.”

Nor does this situation easily fall under the statutory reasons for challenging a grand jury, Dixon said. It has more often been invoked in scenarios where racial discrimination impacted juror selection, or where a juror was ruled “incompetent,” which refers to mental capacity, not truthfulness.

“That really puts us in uncharted territory. We have very sparse case law about when the veil of secrecy can be pierced,” said Dixon. “We don’t have anything that says, ‘Here’s what happens when someone lies to the grand jury.’”

"Where Do You Go From Here?"

Ultimately, Harrell ruled against the defense’s motion to dismiss—and also against a request to reduce the defendants’ bonds.

Harrell didn’t rule on the merits of the claims, in large part because doing so would violate the principle of grand jury secrecy he sought to protect. He would have to allow a discussion of, and even a hearing on, the issue.

Instead, he argued that even if the defense’s claims were true, whatever constitutional violations might have occurred would be dealt with at trial—when those rights are guaranteed. Harrell noted that many constitutional rights aren’t required in grand juries. For example, defendants don’t appear before the grand jury and thus can’t face their accuser.

In the future, Dixon said concerns about the grand jury process would “take somebody crafting some kind of procedure that manages to protect the integrity of secrecy of the process on one hand, while also holding to account the state for any misleading or incorrect information that was presented.”

Dixon added that, short of that, the court could make sure the trial happens sooner. He also said that, at that trial, the alleged perjury of an officer could definitely play a role.

Green’s father said he was frustrated with the ruling and felt that race played a role in it, at least at a systemic level.

“My point is, where do you go from here? I mean, is there any kind of rights for us?” Canty said. “If them boys were white they’d have never went to jail,” Canty said.

Green has been in detention for two years, and the case probably won’t go to trial until May 2024 at the earliest. His father says he’s mostly been held under maximum security in the county jail, wearing shackles for most of the day, even in the shower.

Canty said he’s deeply frustrated that the secrecy of the grand jury has taken precedence over the evidence of perjury in his son’s case.

Knowing now what an unusual occurrence it is to have any evidence from the grand jury, he said he’s concerned how many other times something similar has happened—especially to young men of color—without anyone knowing about it at all.