We received so many wonderful submissions to our 2013 Homemade Holiday Shorts Story Contest that we wanted to share six more of our favorites with you! Every day this week we'll post a different author's story. Homemade Holiday Shorts will air live on December 15th at 6pm on WHQR 91.3 fm. Tune in (or purchase tickets to the live performance) to hear Rachel Lewis Hilburn read the winning story, Mebane Boyd's "Kurisumasu."

A Jar of Good Cheer

A True Story

Nothing signals the start of the Holiday season like the aromas from the oven: warm gingerbread with spicy cinnamon and cloves; buttery cookies topped with peppermint sprinkles, and rich dark fudge that fills the whole house with a bouquet of chocolate ecstasy.

As a speech-language therapist in the public schools, my holiday themes often revolved around my love of food. I could do a month of lesson plans that included counting, categorizing, comparing and contrasting - nothing but food.

In the winter of 1987, one of my groups consisted of five language-delayed special-needs middle school students. My goal was to increase the students’ vocabulary and conversation skills by having them discuss their own family food traditions, and make a bar graph with index cards showing the diversity.

I started the lesson by giving an example of my family’s tradition of crushing fresh cranberries in the food processer with orange juice, sugar and apricot jam.

“Do any of you have any holiday food traditions?” I said.

They all either shrugged their shoulders or shook their heads to indicate No.

“Does anyone eat cranberries at the Holidays?” I said.

Twelve-year-old Ashley spoke up. “Well,” she said, twisting a strand of her long blond hair, which constantly looked like she just got out of a convertible with the top down. “My Mama just opens up a can and dumps it in a bowl and some people eat it and some people don’t. That’s it. We don’t do ‘nothing to it.”

All of the students agreed that their families did the same.

I put up one index card for fresh cranberry relish.

Trying to get them to talk about their own traditions, I told them how I made apple strudel just like my grandmother did in Czechoslovakia. I pantomimed making a ball of dough and then rolling it so big that it covered the whole kitchen table, layering on thinly sliced apples, and sprinkling it with cinnamon and handfuls of sugar, never measuring anything. I pretended to fold it, jelly-roll style before I put it into my imaginary oven. I could almost smell it baking

“Do any of you do anything like that?” I said.

Ten eyes stared silently.

I put one index card with apple strudel on the chart.

These students were being schooled in a rural school district. Most of the men were tenant farmers or coal miners. The three closest towns had populations of 350, 400 and 750, respectively - one stop sign, one gas station and three churches among them. Theirs was not exactly a world of haute cuisine.

“O.K. Does your Momma make pies for the Holidays?” I asked.

“Yes,” they all said, almost in unison.

Eric, lisping through the hole that was left after one of his front teeth had gotten broken in half when he hit a rock while diving head-first into the lake, said, “My Nana makes pumpkin pie.”

“So does mine.”

“We eat that, too.”

“Perfect,” I said. “Me, too.”

We put six index cards with pumpkin pie on the chart.

Kenny, who still hadn’t mastered the “R” sound and sounded a bit like Elmer Fudd, said they eat apple pie. Two others did, too; more cards for the chart. We were on a roll.

All five ate green beans that their Mamas had canned. Four ate mashed potatoes. They talked about helping to dig “the spuds” out of the dirt or carrying them out of the root cellar. Four families had stuffing but some of the students didn’t eat it and asked if they should still put on an index card. The group decided they should since it was a family tradition.

The student who did not have turkey was a fair-skinned redhead with a face covered with freckles and a grin that made you wonder what he'd been up to. It was impossible not to smile back at him.

The bar graph was growing nicely.

“We eat turkey at our house,” I said. “Who eats turkey for the Holidays?” Four hands went up.

The student who did not have turkey was a fair-skinned red head with a face covered with freckles and a grin that made you wonder what he’d been up to. It was impossible not to smile back at him.

“What do you eat, Bobby?” I asked.

“I don’t know. Whatever Uncle Chuck shoots. Rabbit. ‘Possum. Raccoon. You like raccoon?” he asked me.

“Don’t think I’ve ever had it.” I said.

“That’s some good eating,” Bobby said.

“And deer.” Bobby almost jumped out of his seat. “Uncle Chuck and Louie gonna take me deer hunting this year; they promised. I can’t wait to shoot me a deer.”

“You ever eat squirrel?” Bobby asked.

Most of the children had eaten it; I had not.

“That’s nasty.” Ashley said.

“I don’t like squirrel neither,” said Eric.

“In my family, you eat what’s put in front of you. If your Momma done gone through all the trouble of fixin’ something, you better not be turning up your nose,” Bobby said. I could almost hear his mother’s voice.

I was about to tell them that squirrels were members of the rodent family, but I kept that to myself. I had to fight the image of seeing a rodent on my plate surrounded by mashed potatoes and peas.

We added five index cards with “turkey” written on it. We did not put a card for any of the wild game.

At the end of the lesson, we compared the foods on the graph. I had been hoping to find examples that made each student - each family – uniquely one-of-a-kind. Instead, the students found their similarities, the shared rituals that united them, binding them not only to each other but also to their community, to their world.

During the forty-five minute drive home, I re-played the tape in my brain of what happened with the group.

“What’s a tradition, anyway?” I thought to myself. I took a deep breath and exhaled slowly.

“For these kids, opening a can of cranberries is their family tradition. Eating whatever Bobby’s uncle kills is the tradition, even if he kills something different every year.”

I wondered if any of them ever went to bed with their stomachs growling, if they even had a bed. And I knew exactly what I needed to add to the chart.

On the last day before the break, I had a little party with all of my students. I brought in homemade gingerbread cookies and store-bought apple cider. We played Uno and sang “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

When Bobby came in, I noticed that he had on the same wrinkled short-sleeved shirt that he had worn all week and which seemed terribly inadequate for the cold weather. He handed me a brown grocery bag.

“This is for you,” he said.

“What is it?”

“You gotta see for yourself. Open it.”

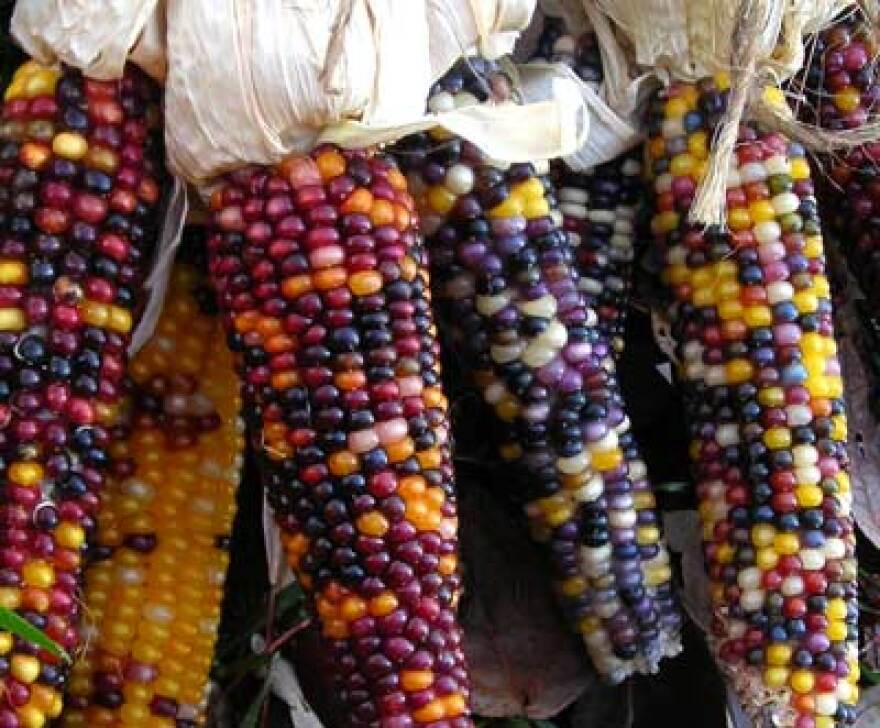

I peeked inside the bag and took out what looked like an old mayonnaise jar filled with red, white, yellow and purple seeds. Without saying anything out loud, I looked at him, my eyes asking what it was.

“It’s popcorn. I done ‘em myself. See, first you gotta shuck the shucks, then you put two ears together and rub them back and forth like this and the popcorn falls right off,” he pantomimed.

“Did you grow the corn, too?” I asked.

“Yes, Ma’am.” His eyes sparkled and his grin filled his whole face.

“Wow,” I said. “This is the nicest gift anyone has ever given me.”

“Thank you, Ma’am.”

I gave him a hug and said, “I don’t have anything for you.”

“That’s OK. I got all I need. My momma says it’s better to give than to receive. I’m giving you this ‘cause you’re my favorite teacher.”

“Thank you.” I said. I was at a loss for words.

“Popcorn fills you up when you’re hungry. It’s real fresh. You’ll like it. You gotta put salt on it, though.” Bobby said.

“Does your Mama know that you are giving me a whole jar of this? It’s so much.” I said.

“She knows. She’s the one who fetched me the jar. We got lots of popcorn. Don’t you fret none,” Bobby said.

I turned my head away so he couldn’t see me wipe my eyes.

During my lifetime, I’ve given and received hundreds of presents, worrying for hours over my “wish list” or searching frantically for the perfect gift to give. Yet, I can recall so few: pajamas from Grandma, a hard-back copy of Little Women from Aunt Rose, a silver dollar from Uncle Gus.

And, a used mayonnaise jar of homegrown, hand-shucked popcorn, one of my favorite gifts of all. Happy Holidays, Bobby, wherever you are.

Pat Walters Lowery is a retired speech therapist. She had worked for over 40 years with children with communication disorders. She is now in the Pomegranate Books Writing Group.