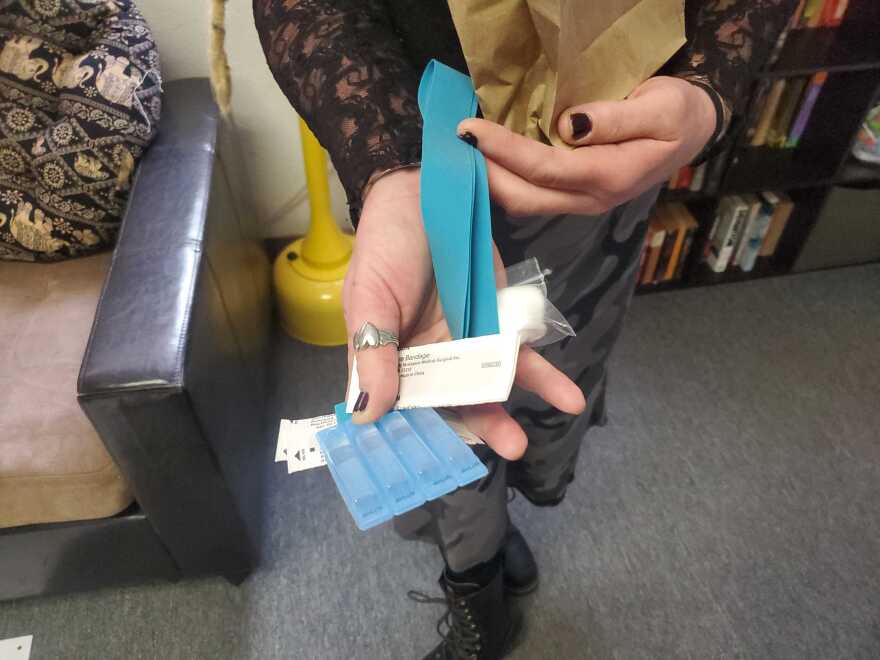

In single-story red brick building to the south of downtown Greensboro, Tanya Russell unpacks the contents of a brown paper bag.

"Our kit has everything you need," she says. "It has sterile water, alcohol pads so you can clean the area that you're going to inject to. Band-Aids. Tourniquets. Cottons."

These kits contain everything to take drugs, excluding the actual illicit drugs.

"We also have smoking utensils for people who are smokers, and then we also have snort kits for people who are snorters," Russell says. "We try to be a little more diverse for drug use. We want to tap all areas, not just for injection drug users."

This is North Carolina Survivor's Union. It's a place where people with substance use disorder can come for help. The strategy here is all about harm reduction. It meets people where they are and its strategies aim to decrease the negative consequences of recreational drug use without requiring abstinence.

"We are a drug user union, which means we work with people who actively use drugs, and try to provide harm reduction services, and engage in social justice work," says Louise Vincent, the executive director of the Survivors Union.

The work happening in harm reduction circles is more important than ever. Drugs like heroin are now routinely laced with extremely potent substances like fentanyl and xylazine. And increasingly, those substances are making their way into drugs like cocaine, extacy and black market pills as well.

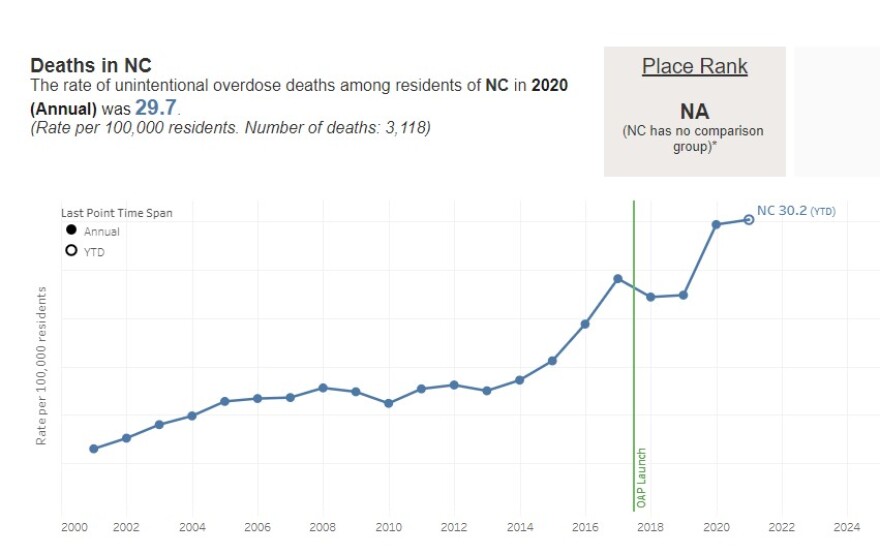

This has driven an enormous spike in overdose emergency visits and deaths. According to N.C. Department of Health and Human Services data, there were 4,000 overdose deaths in North Carolina in 2021. That's up some 50 percent since 2019.

The harm reduction strategy is simple: Allow people to safely use drugs. Even if they are illegal, this prevents further harm. Clean needles stop the spread of diseases like Hepatitis C or HIV. Testing drug batches gives people an idea if their heroin is laced with fentanyl.

"When we don't use harm reduction methods, people die," Vincent says. "When we insist that people, 'Well, I'm not going to work with you until you are willing to stop using all drugs.' I mean, what are we (doing)? People come to get help. And they say, 'I can't stop using drugs.' And then we say, 'You better stop using drugs if you want help.'

"That doesn't even make any sense. Like, we got to do better, man."

Fentanyl is an extremely powerful opiate, and xylazine is a potent sedative. It's arguable that it was inevitable that the United States drug supply would ultimately become flooded with these substances, but the pandemic helped spur it on.

"It was a simple issue of supply and demand," says Nick Matthews, co-founder of Stillwater Behavioral Health who helps people recover from substance use disorder.

In many ways, the market for illicit drugs behaves just like any other market. When COVID-19 caused a huge decline in international travel, it became harder to get drugs into the country. That's when xylazine and fentanyl flooded the market.

"Fentanyl is wildly powerful," Matthews says. "And if you have an addiction to opiates, one of the first things that you realize is that tolerance is a real thing. And that what you were using, immediately stops working."

The body becomes acclimated to the opiate, and it craves a stronger dose. This is how people can progress from legal prescription medications like Oxycontin to heroin or worse.

"But even full blown heroin IV stops working," says Matthews. "And we call that getting well, instead of getting high, because you're in withdrawal. And then you will take the same amount of heroin that you took yesterday, and you won't feel high, but you just feel normal."

There's a useful way to protect against fentanyl: test your drugs to see if they are laced with it. Clinics around the state are passing out test strips so people can see if fentanyl is mixed in with their heroin or cocaine.

The North Carolina Survivors Union clinic in Greensboro has a sophisticated machine that gives far more detailed information about a drug sample than a test strip. It has an infrared spectrometer which can run a precise scan on any batch of drugs.

Don Jackson operates the machine at NCSU. He wipes down the crystal in the center of the table where drug samples are poured.

"I don't even need that much," Jackson says, pouring out an off-white colored powder from a red bag marked "collection sample."

The infrared spectrometer is connected to a laptop that will give a reading. Mary Figgatt is a doctoral student at UNC Chapel Hill studying epidemiology. She also co-leads the UNC drug checking program. She sometimes helps Jackson with the testing and describes what's going on.

"It takes about 25 different scans," she says. "And then it'll consolidate all of that information, and then it'll output it here. And then we'll do the analysis."

On the computer screen, two thin lines begin to trace up and down. They look kind of like peaks and valleys of a stock chart on a wall street analyst's computer. This reading gives Don and Mary information about what's in the sample.

"Look at that," says Jackson.

"So this right here, looks like it might be fentanyl," says Figgatt, pointing to two lines that match up almost perfectly.

"Yup," says Jackson. "That's it."

"Folks were not prepared for the level of fentanyl that has been put out in the street," says Michelle Mathis, the executive director and co-founder of Olive Branch ministry, a faith-based harm reduction clinic.

Michelle Mathis and Louise Vincent don't work in the same location, but both use very similar harm reduction strategies to help people with substance use disorder.

"Our drug supply is so absolutely contaminated, that we are seeing people come in with skin and soft tissue infections that are the worst I've ever seen, that will bring you to tears," says Vincent, becoming emotional herself.

Mathis says her team has coined the phrase "sleepy meth."

"You inject the (crystal) meth, and you get a quick bump, and then you fall out, or you simply go to sleep for hours," she says. "And people will say, 'Well, you're not supposed to do that on that. I don't understand. It's a bad batch.' And I'm like, 'No, honey. Did you test it? Did you test it for fentanyl?'"

Both Mathis and Vincent believe it's possible to stem the tide of overdose deaths. But it requires a continued shift away from stigmatizing people with substance use disorder, and instead a better understanding that addiction is a brain disease similar to diseases like asthma or cancer.

Mathis says it's not unlike a need to drink caffeine every morning, or eat sugar after dinner.

"Our brains are rewired for that. And when you try to quit using even something as simple as sugar or caffeine, we go through irritable, painful times. But that's not seen as a moral failing," she says. "But when someone puts opioids into their system and their brain is rewired, that is seen as a moral failing."

Vincent says she believes better outcomes are achievable.

"There's a way through this, and there's a way to do this. Getting rid of all the drugs on the planet isn't going to make us live in a utopia," she says. "Drugs aren't evil. There's a million different ways that we can we can treat people; but when we treat them with dignity and respect, it changes things. And it changed everything for me."

Copyright 2022 North Carolina Public Radio. To see more, visit North Carolina Public Radio. 9(MDA4MDc0NDkyMDEzMTQ4ODU0MTE0OGNiNg004))